|

|

| By Seth Cropsey It is 10 years since the Greek coalition fought their way on to Troy's wide beaches — longer than anyone expected — and still both sides persist. Just when one side seems close to victory, the other struggles back to its feet. The past few days have been disastrous for the Greeks because their most fearsome warrior, Achilles, has withdrawn from the fray after arguing bitterly with the coalition's commander, Agamemnon of Mycenae. So serious is the rout caused by Achilles' absence that twice in the past week, the Greek commander in chief has counseled abandoning the fight and returning home. The third time Agamemnon urges his coalition to give up and sail away, Odysseus confronts him bluntly: "You must have lost your mind. Your plan will ruin us." |

Detail of Achilles, the central character and greatest warrior of Homer's Iliad. He is portrayed as the only mortal to experience consuming rage |

| The directness with which leaders speak to one another in wartime has changed in the roughly three millennia since Homer, but the dependence of victory on good leadership has not. Agamemnon will now be tested as he has not been throughout the war. The wall and trench the Greeks had built to protect the ships they sailed to Troy had been breached. The Trojans would never allow Greek forces to board their ships unmolested, to retreat without paying dearly. A lop-sided action at the point of embarkation would unfold, and the slaughter would probably lead to the burning of the ships and the destruction of the entire force. More important, defeat would signal the civilized world that the most fundamental international norm — that of the proper relations between guest and host — had been violated. The war began when a Trojan prince the guest of a Greek king had spirited away his host's beautiful wife, Helen. Rescuing her would sustain the civilized world's order. Abandoning her would help tear it down. Odysseus was right. Agamemnon's retreat would have turned a tactical reverse into a strategic catastrophe. Homer's "Iliad," the first great work of western civilization, is a rich and complex tale of anger, fate, war, humanity, and what we can, and cannot, hope to know, or control. It is also a commentary on wartime leadership, and on the virtues and vices of commanders. The subject of command is close to the poem's core. However, before looking at what Homer thinks about command, modern readers must appreciate how thoroughly practical is his understanding of war. The fog of scholarship needs lifting to see this. |

|

The place of the gods, and the connection of the great heroes to warfare conducted by mortals who cannot trace their lineage to Olympus have intrigued listeners and then readers for millennia. Contemporary scholarship is saturated with these topics as well as such others of less obvious interest as the "Iliad's" internal mechanics — its organization, poetic allusions, similes, and metric structure. Other scholars critique one another's translations, and seek to understand what Homer can tell us about his own times, about the development of the idea of Greek culture, and the effect of the "Iliad" and Odyssey on Greece at its heyday, at least four centuries after Homer lived. |

A bust of the legendary poet, Homer, author of the Iliad. |

| With few exceptions, such as Barry Strauss' recent "The Trojan War: A New History," academic research on Homer nowadays often looks at his work as merely a key to the world from which it came. Less important in learned writing is the possibility that the "Iliad" survived over the centuries because its understanding of men and conflict is universal. This article starts from the premise that Homer deserves to be read because his insight into war as a human activity stands for all time.

Current events also make Homer especially interesting. The spiritedness that drives his characters and propels his story may no longer describe the network-centric western militaries that rely increasingly on the ability to process information. But the radical fanatics who would destroy our civilization are as spirited and passionate about their lives and deaths as many of the men Homer describes. Although there are important differences between those who fought the Trojan War and today's enemy, the ancient poem offers us a glimpse into the minds of people whom we must understand if we are to defeat.

The path to the "Iliad's" vision of human character and leadership begins with the work's grasp of fundamentals. Homer knew about war and cared about describing it. His storytelling demonstrates a meticulous grasp of tactics, technology, alliances, logistics, and the art of marshalling these, leadership. Homer on War Much more numerous than such famous warriors as Achilles and Hector are the "Iliad's" foot soldiers, minor characters who stand out for their deaths rather than for how they lived. In Book IV, for example, a Trojan ally, Peirus, who appears only once kills a minor Greek character, Diores: Peirus, the Thracian leader, had caught him/Just above the ankle with a jagged stone/That crushed both tendons and bones/He fell backward into the dust, hands stretched/Toward his friends, gasping out his life/Peirus ran up and finished him off/With a slicing spear thrust near his navel/His guts fell out and everything went black. (I, l.570) An instant later, a spear penetrates Peirus' lung; its thrower unsheathes a sword and dispatches him with a flesh-opening thrust to the stomach. His death is additional evidence of the ferocity of combat with pointed and edged weapons, and the grimness of the front lines. There are hundreds of such encounters where foot soldiers whose only identification is their parentage or birthplace crush, stab, and hack each other to deaths that are dignified chiefly by the inclusion of the fallen's name in the poem. Less fortunate are scores more of ordinary soldiers on both sides who perish in battle without being named. Gods and heroes with divine ancestors move the "Iliad's" story forward, but the vast majority of combatants on the battlefield Homer created are men and need to be led. Homer's interest in tactics follows logically. Tactical details appear throughout the work. Early in Book VIII Homer describes the positioning of the Greek armada as it sits along the beach with prows pointed seaward — to allow a quick departure if necessary. Homer knows that the flanks of a military or naval force are critical. The great warrior Ajax protects one flank, Achilles, the greatest, the other, and the cleverest contingent commander, Odysseus is positioned directly at the center "so that a shout would reach either end of the camp." (VIII l.223) Similar tactical care shapes the Greek line as it moves to engage the Trojans — and it is not heroes who carry the burden when the opposing vanguards clash. The old commander, Nestor of Pylos: Positioned the chariots in front/And massed the best foot soldiers at the rear/Within this double wall he stationed the riffraff/So that willing or not they would be forced to fight. (IV, l.318) Nor are such dispositions fixed. Another commander, one of the two Ajaxes, allows his armor-less archers to do their work by positioning them in the rear, behind "troops in full battle gear" (XIII l.761)," who are engaging the Trojans directly. It works. For the moment, the cloud of arrows deprives the Trojans of their will to fight. Greek troops who await a Trojan probe aimed at breaching the hastily built defensive wall that protects their camp and ships are arrayed in compact formation, Spear on spear, shield overlapping shield/They stood helmet to helmet, the horsehair plumes/On the burnished crests brushing each other/When they nodded, and when they shook their spears/The shafts tickered against each other?… (XIII l.33) Homer knows that discipline matters, and that it enables tactical maneuver which in turn saves one's own troops' lives as it chews up the enemy. He only puts sound tactical advice into the mouths of warriors like the two Ajaxes, or advisors like Nestor, men who are not subject to the anger that distorts Achilles' or Agamemnon's judgment. The greatness of the latter two warriors, Homer implies, has little to do with the experience and judgment needed to command troops and win battles. |

|

| Technology is also important in the "Iliad." Achilles sallies forth into battle with weapons and armor crafted by the god of the forge, Hephaistos. But men who are not the sons of goddesses have to depend on mundane equipment. The "Iliad" is full of descriptions of human-made shields, corselets, greaves, swords, helmets, axes, grappling pikes, javelins, bows, arrows, and other weapons. Some of these descriptions are strikingly beautiful. Some show the poet's familiarity with technical details: the fit of a helmet at its wearer's temples, the balance of a heavy shield, the flexibility of armor that allows a combatant to move freely. Others show that Homer also appreciated the connection between personal gear and tactical requirements. |

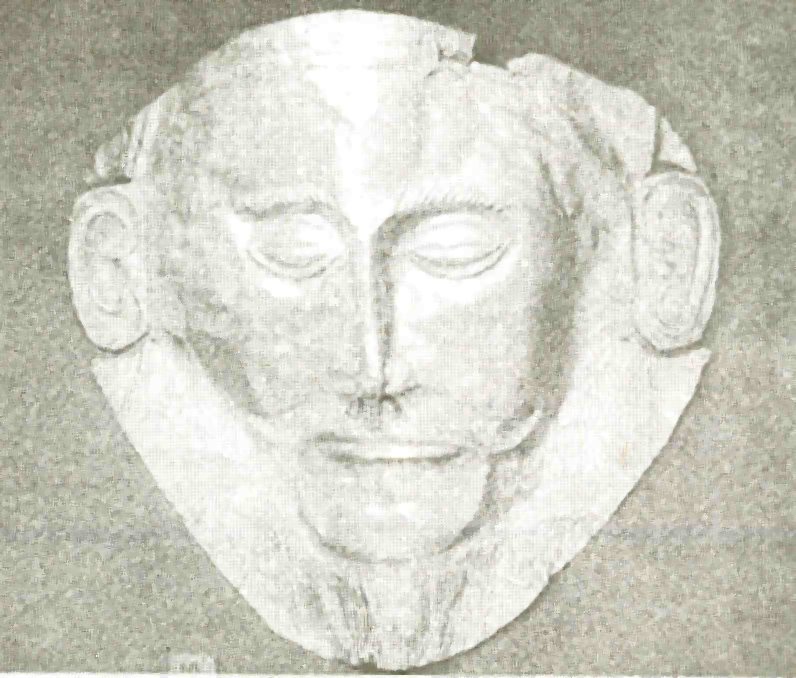

The Mask of Agamemnon discovered byHeinrich Schliemann in 1876 at Mycenae. Although not the equal of Archilles in bravery, Agamemnon was a dignified representative of kingly authority. |

|

The "Iliad's" 10th book takes place after an unsuccessful embassy to make peace with Achilles and coax him back into action. Troubled and bereft of a plan, Agamemnon summons the great warriors. Nestor suggests a night reconnaissance expedition to learn Trojan intentions. It will be a small operation. The men dress appropriately. No shining bronze helmets or polished shields that reflect light, and no greaves that clang each time one leg passes the other. Diomedes wears a simple leather helmet "without horn or crest." Odysseus also chooses an animal skin helmet. Although decorated with boars' teeth that could reflect light, it is lined with felt, a reminder of Homer's appreciation that missions such as this require stillness and stealth. At the same moment, and in the opposing camp, Hector asks for volunteers to undertake a similar attempt to secure intelligence about the Greeks. Dolon, a hapless, witless foot soldier dons a weasel skin helmet along with other non-reflective gear, a "grey wolf skin." Dolon, however, does not grasp that a sprinter is noisier than a man who glides silently through the night. Odysseus hears Dolon running, sets a trap, interrogates him, and gains valuable intelligence about the enemy's camp. When the unfortunate Dolon finishes blabbing, Diomedes kills him insisting that if released he will return to spy on the Greeks some other time. Homer appreciates operational security, and understands both the value and requirements of small unit, night operations. He also knew a thing or two about alliances. Odysseus asks the unfortunate Dolon whether the Trojans are camped among, or separate from, their allies. They are bivouacked separately. The prisoner also discloses the location of each of the allies including the identity of the most recently arrived contingent, the Thracians. Odysseus and Diomedes head straight for the Thracian camp, and kill 13 of them including their king, Rhesus. Again, it is important to remember: the gods move in and out of human affairs in the Iliad, but Odysseus' sensible idea of demoralizing the Thracians, and perhaps driving them out of the Trojan alliance is entirely his own. Trying to shatter alliances by inflicting casualties and driving off the lesser partners remains a standard tool to achieve military and diplomatic ends. As do financial incentives. Homer says that a Corinthian, Euchenor, chose to fight alongside the Greeks rather than die at home of a painful disease — as had been prophesied — or pay the heavy fine (Bk. XIII l. 702) demanded of those who shrank from Agamemnon's call to arms. Homer's combatants fight for plunder, glory, honor, and preserving international norms, but the bottom line is the bottom line: failure to join the alliance carried a heavy fine. Troy preferred the carrot to the stick. There are more specifics about Troy's alliance-building strategy. Hector implies that neighbors run the same risk of attack from Greek aggression in his exhortation during the melee over Patroclus' body. I thought you would fight with willing hearts/To save the Trojan women and children/From these war-mongering Greeks. This is why/I have been feeding you at our expense/And giving you gifts to keep up your morale. (XVII, l.225) But, as he explains without apology, Troy is also covering the allies' expenses and paying them for their service. There is nothing divine or heroic about this. Trojan alliance policy is based on the calculation of its neighbors' self-interest, and conducted by payment. The character of command Details of warfare support the "Iliad's" action. But Homer aims higher than excellence at tactical description. As the story's first line explains, the subject is anger, its causes and consequences. The Iliad, however, would be a thin story, and one that does not reflect human experience if spiritedness were the characters' sole trait. Homer's mortals also demonstrate high intelligence, judgment, compassion, and courage. The heroes can be divided into two groups, those whose actions and words move the story forward; and those whose preeminent combat skills also earn them a place in the tale. If the men whose greatness consists chiefly of skill at combat are considered as a group — for example the two Ajaxes and Diomedes on the Greek side, and Sarpedon and Aeneas on the Trojan — five principal mortals remain. Achilles and Agamemnon, a pair of spirited leaders; Odysseus and Nestor, also kings in their own right, and men who can be relied upon for clever, wise, objective advice; and Hector, leader of Trojan and allied forces in the field. One pair is spirited. The second is clever. The third, Hector, mixes the characteristics of the "Iliad's" great men. In these three groups, Homer presents a spectrum that remains Western literature's most discerning reflection on the human qualities best suited to command. Everything that unfolds in the "Iliad" is launched by a double exercise in the Greek commanding officer, Agamemnon's, angry and dubious judgment. A priest of Apollo approaches Agamemnon with a large ransom for his daughter who was carried off in a previous conquest. He asks Agamemnon to... Give me my daughter back and accept/This ransom out of respect for Zeus' son/ Lord Apollo, who deals death from afar. (I, l.27) Agamemnon insults the priest, and sends him packing. Terrified, the holy man slinks away, and prays to Apollo. A plague descends on the Greek forces killing pack animals, hounds, and finally men, until the beaches burn hotter with funeral pyres than the sun's rays. Not content with offending the gods, Agamemnon insults the most powerful and feared warrior in the coalition, Achilles. Another divine tells the Greek commander that the only way to lift the plague is to return the girl to her father. Agamemnon scorns this man too, but agrees to surrender the girl. However, he angrily stipulates that Achilles must compensate the loss by surrendering a girl, Briseis, who had been awarded to him for valor in combat. What is it like to have one's rewards for courage and skill under fire taken because a commanding officer wants them? Achilles swears that he will withdraw from action until the Trojans' slaughter makes the Greeks "appreciate Agamemnon for who he is." ( I, l.427) Agamemnon rejects his aged subordinate commander, Nestor's advice not to expropriate Achilles' prize, and Briseis is transferred to Agamemnon's household. Achilles appeals to his mother, Thetis, who implores Zeus to make the Greeks pay in blood until her son's honor is restored. The chief Olympian nods his assent, and the "Iliad's" action is launched. Was Agamemnon's behavior a lapse in his otherwise prudent command judgment? Hardly. As an allied commander Agamemnon is a mess. Directed by a heavenly messenger in a dream to initiate an assault on the Trojans, Agamemnon decides first to test his troops' mettle. After privately instructing his subordinate commanders to persuade the troops to stay, Agamemnon summons an assembly, declares his frustration with the long war, complains that no end of hostilities is in sight, despairs of victory, and urges the men to follow him back to home and family. The Greek assembly heads for the ships. Order is only restored when Odysseus persuades the multitude that a snake they had seen devour a family of nine nesting birds augurs eventual victory. Agamemnon's test rocked the coalition, and might have destroyed it. Nestor admonishes him to "assert yourself and resume your command of the Greek forces (II, l.373)." There may be something to be said for expressing misgivings (although for a very different fictional approach to the same situation consider Gregory Peck's words to his men in "Twelve O'Clock High": "Fear is normal. Forget about going home. Consider yourselves dead.") But what sort of commander would tell his men to surrender to fear, and then shift responsibility to subordinates for persuading the troops not to do what the commander counseled? What kind of commander doesn't know his subordinates? Here too, Agamemnon's spiritedness clouds his judgment. The order to engage the enemy travels as fast as one unit can transmit it to the next. Rather than lead from the center or front, Agamemnon goes along the line browbeating his troops. But why carp about Odysseus and Diomedes, two of the greatest Greek heroes? As they wait to receive the signal to advance, Agamemnon tells the former that when there's a feast, Odysseus is always first in line for meat and wine, but that now, "you'd be glad to see ten Greek battalions carving up the enemy ahead of you with bronze (IV, l.369)." There is no evidence in Homer — or anywhere else — of the Ithacan ruler's malingering. The insult is undeserved: Odysseus scowls, and Agamemnon retracts it. Agamemnon moves along the line and tells Diomedes that his father was a great warrior but that his son is better at talking. Again, there is no evidence that Diomedes ever needed prompting. In the next chapter he fights with a god. The Greek coalition leader continues to badger his greatest warriors, a practice that he began with Achilles. In combat, Agamemnon is equally mistaken about his subordinates. The hero Teucer has just downed eight Trojans: nothing suggests he has decided to rest. Nevertheless, Agamemnon approaches with an offer of gifts if Teucer will "keep shooting like this." Teucer responds, "Most glorious son of Atreus, why urge me on when I'm at my top speed (VIII, l.296)?" What does qualify Agamemnon for command? The poet explains, not once, but twice: his looks. As the "Iliad's" first clash between Greeks and Trojans approaches, Agamemnon inspects the troops. Homer describes him: The look in his eyes, the carriage of his head/With a torso like Ares', or like Poseidon's/ Zeus on that day made the son of Atreus/A man who stood out from the crowd of heroes (II, l.516)." In the next book, Helen joins the Trojans who gather on the city's walls to witness the contest between her once husband, Menelaus, and the man who abducted her, Paris. Priam, king of Troy, and father of Paris and Hector, doesn't recognize the enemy's leaders. He asks Helen: Now tell me, who is that enormous man/Towering over the Greek troops, handsome/Well-built? I've never laid eyes on such/A fine figure of a man. He looks like a king (III, l.174). It is Agamemnon. |

|

| The Above, presented as the first of two parts, was published in the January 2007 issue of the Armed Forces Journal. The original title is, "Homer's Greek Epic Offers Leadership Lessons for Modern Warrior." | |

|

(Posting date 31 January 2007) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|