|

||

|

Tracking Dolphins in Amvrakikos Bay

|

||

|

By Diana Farr Louis

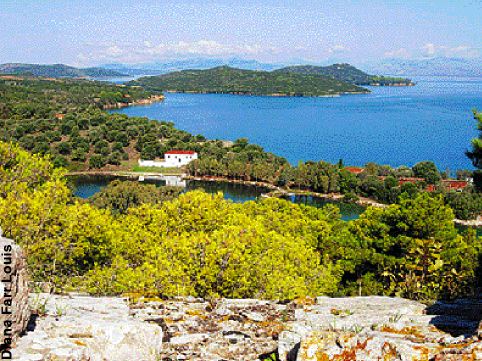

Amvrakikos is the largest of Greece's wetlands. In this lonely haven of marshes, reedbeds and saltflats two environmental organisations are trying to preserve a rich ecology and raise awareness about the area's precious and unique qualities and wildlife The voice on the other end of the line belonged to my brother who was calling from Montana. Dolphins in the Amvrakikos! Who knew? The Amvrakikos bay, the largest of Greece's wetlands, is separated from the Ionian Sea at Aktion by a channel so narrow it takes a whole year for the water to renew itself. The north coast is an elaborate pastiche of marshes, sand spits, reedbeds and saltflats, formed by the deltas of the Arachthos and Louros rivers. It also contains at least 24 lagoons, natural aquariums for a huge population of fish, shrimp and the country's biggest concentration of eels. |

||

The deeper waters of the south coast, overlooked by lush hills and a castle or two, are home to dolphins and sea turtles attracted by the abundance of easy prey. In addition to sea creatures, the number of bird species recorded there varies between 250 and 294, depending on which study you read. The bay is protected by Ramsar and Natura 2000, a government consultancy protecting natural habitats. However, the bay is threatened by pollution from agricultural chemicals, dams that reduce the flow of fresh water into the lagoons, illegal trawling and oil refineries at Amfilohia. Despite all this, the Amvrakikos rarely makes news. I had never given it a moment's thought on the many occasions when we sped by on the way to Lefkada, Igoumenitsa or Yannina. After my brother's call, I googled it. The first site that pops up is that of Tethys Research Institute and within minutes I was spellbound by a gallery of photos of dolphins playing, fishing, diving, soaring, lazing, eating, alone or in groups. I learned that some 130 individuals had been identified on the basis of close-ups of their dorsal fins that bear characteristic markings as personal as our fingerprints. I also discovered that while these bottlenose dolphins seemed to be thriving in the Amvrakikos, their common dolphin cousins in the Ionian itself were rapidly becoming a rarity. |

||

Tethys, named after the hypothetical primeval sea between Godswana and Laurasia, was founded in 1986 as "a non-profit NGO dedicated to the preservation of the marine environment... particularly cetaceans" in the Mediterranean. Its headquarters are in Milan and Venice but it conducts studies in places like Ischia, Liguria and Kalamos in the Ionian. Because so much of its work relies on the assistance of volunteers, it was natural that at some point Tethys would attract funding and sponsorship from Earthwatch, the international organisation that helps environmental projects round the world. This year marked the first year of cooperation between Earthwatch and Tethys as well as Tethys' first summer with a base at Vonitsa on the north shore of the Amvrakikos. |

||

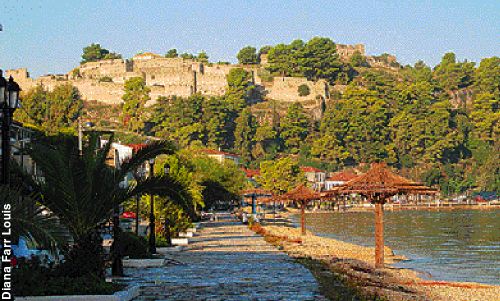

| My brother had signed up for the last volunteer team of the season, so we drove to Vonitsa to meet him at the end of September. The village was in the throes of pre-election improvement fever, with back streets being torn up and paved with cobblestones, and a surprising number of charming vintage two-storey houses already restored. Palms and thatched umbrellas framed the waterfront with its smattering of low-key cafes, a cluster of yachts floated beside the jetties of a marina in progress, and the grey walls of a massive castle competed with pine trees for domination of the hill just above it. When we pulled alongside our hotel, a young woman ambled in from the narrow beach to take our names and give us our key. Then she went back to fishing for squid with a handline. Vonitsa doesn't attract many foreigners, though there's no reason why it wouldn't make a pleasant base for a holiday, especially if you had a small boat. For Tethys, it was a perfect choice - small, unspoiled, conveniently located and boasting a sizeable number of fishermen. Predictably, fishermen abound in the Amvrakikos but because its waters are protected, only artisanal fishing is allowed: small boats and lagoon traps, but no trawlers or purse seiners (gri gri). One of Tethys' research methods, apart from scouting for dolphins and photographing them from an inflatable boat, is to question fishermen about sightings, in order to determine whether the population seems constant, larger or smaller than in the past. |

||

The project director, Joan Gonzalvo Villegas, a Catalan biologist from Barcelona, was going to collect us from the hotel and walk us to the Earthwatch house/study centre. He called to say he'd be late. He had to take samples from a dead dolphin spotted by a Vonitsa fisherman. Clearly, Joan was well on his way to establishing good relationships with the locals - another Tethys goal. As he told us that evening over a lamb stew cooked by my brother: "Of course, the research is important, but I'll consider the project a success if I can just manage to raise public awareness, especially among the young, and respect for the environment in general. We don't want to stay here for ever. Instead we hope to educate a few young people about the wonders of nature and what we can do to keep the bay healthy." |

The Vonitsa waterfront and its Byzantine/Venetian/Trukish castle |

|

| Joan (pronounced Joe-Ahn) is passionate about his work. "From our base at Kalamos I saw a drastic drop in the common dolphin population in just five years. We speculate that overfishing has caused it. Ninety percent of the top predators - tuna, swordfish - have disappeared so fishermen are targeting the smaller, cheaper fish that the larger fish and dolphins usually go after. I don't want to see that happen in the Amvrakikos." Being at the top of the food chain, dolphins are bio indicators of the overall health of the ecosystem. It is hard to get excited about shortages of krill or contaminated plankton, but as my brother says, "Dolphins are to the sea what pandas are to the land - beautiful, loveable animals that we can identify with and care about. What happens to them will eventually affect us, too." Mediterranean peoples have been fascinated with them since earliest times. Fresco artists portrayed the common dolphin on the walls at Akrotiri (Santorini). Museums are full of vase paintings of dolphins, statues large and small, coins and jewellery, while today you'll find them emblazoned on everything from T-shirts to ashtrays. |

||

| But Joan says: "Just because they seem to wear a smile doesn't mean they're cute and cuddly. These are the lions and tigers of the sea, and when we observe them we try not to interfere with their behaviour. They can usually escape us when they want to." Joan would like to get sailors, flotillas and marinas involved in reporting to Tethys on the dolphins they see. The Institute already works with schools and some local authorities at Palairos, opposite Kalamos on the Ionian coast. He warns against chasing them to get a closer look. Dolphins (and whales) have been known to panic when crowded by overenthusiastic "watchers" who think they are playing. |

Bottlenose dolphins are thriving in Amvrakikos |

|

Across the bay is another group of people intent on preserving the Amvrakikos. We discovered the Rodia Wetlands Centre completely by accident. It had been a disappointing day. Apart from a shrimp feast at Menidi, the best place for that pause that refreshes between Amfilohia and Arta, all our searches had been in vain. A supposed ecological centre at Kopraina had closed for the weekend and the crone presiding over a greasy spoon of a tavernaki there was unwilling to tell us anything about it, the magnificent Panagia Parigoritissa in Arta was shut down for repairs, and somehow we couldn't locate the 10th-century Panagia ton Vlachernon - as usual the signs petered out before fulfilling their function. Our only consolation, the famous Arta bridge was unmissable. But heading west towards Preveza, we were diverted off the main road by an arresting sign for a Roman villa. Every time we were about to turn back, another would appear to lure us on deeper and deeper into flat, reedy swampland. The signs stopped at what proved to be a Roman oil press, a collection of massive millstones that resembled modern sculptures. But they also led us to the Rodia Wetlands Centre. |

||

This outpost is the starting point for boat trips into two of the bay's biggest lagoons, Rodias and Tsoukalou. Unexpectedly, it is the creation of a monastery in the vicinity, Prophitis Ilias, whose monks are all highly educated. Under Abbot Father Agathangelos, it "seeks to promote an alternative, God-centred environmentally-friendly view of nature, based on Christian principles, as applied for centuries by the monks who owned the wetlands". Founded three years ago, the centre conducts tours daily except Sunday and we made arrangements to join a group a few days later. After a short briefing about fishing practices and bird life (but no Christian indoctrination) in a room hung with attractive information panels, our young guide Dimitris (no monk) shepherded us to the boatshed. |

Red nets drying at the fishermen's hut add to the fragile beauty of the wetlands |

|

|

The next three to four hours brought us into intimate contact with the serene immensity of the lagoons, which are separated from the bay proper by spits formed of a myriad shells. Dimitris showed us where to aim our cameras and binoculars, alerting us to the silent presence of greebes, egrets, all sorts of herons, marsh harriers, stilts and the elusive kingfisher. He also kept up a steady discourse about Dalmatian pelican nesting habits, the growing herd of water buffalo started with recruits from Kerkini, the impossibility of persuading old timers to stop jettisoning their trash, and the mysterious life cycle of the eel. Dimitris was equally knowledgeable about the Panayia tis Rodias, built in 970 at the edge of the marsh and littered with confetti from a recent wedding. It boasts the smallest dome in Epirus and brightly coloured frescoes painted in 1884 by three brothers who made their pigments from flowers. Our most interesting stop was the fishing hut cum chapel on stilts just a metre above the glistening water. A concatenation of thick poles, wooden walls, thinner sticks and unseen nets linked by a weathered boardwalk surrounded it. They formed an ivari, a word probably derived from the Latin vivarium, a natural tank where fish, or in this case eels, are raised and eventually trapped. Dimitris walked onto the bow of what looked like a half-sunken boat, wrestled with the cover of the hold, stuck in a long-handled net and pulled up a few wriggly eels. No one knows why eels begin and end their lives in the Sargasso Sea or how they discovered the Amvrakikos, but in the winter fishermen may catch up to a tonne in one night and between 70 and 80 tonnes a year. Scientists estimate that is about a third of the bay's total, most of which are exported to Italy. As we were leaving the dappled world of red and green marsh grasses for the open lagoon again, shots cracked the silence. In the distance a speedboat streaked over the glassy surface. Then it came to an abrupt stop and one of the passengers pulled out a trident and pretended to fish. "They're duck hunters, illegal, but what can we do?" said Dimitris. "The coast- guard's all the way over in Preveza and even if they came, they'd never catch these guys." This is not a park or a zoo or a game reserve, as Dimitris had said earlier. I thought about what Joan had told us back in Vonitsa. "With Greece accounting for 40 percent of the Mediterranean's total coastline, it has the potential to lead the way in protecting it. And the Amvrakikos is a good place to start, not just for the sake of the dolphins but for all the other species that live here." Obviously, Tethys and the Rodia Wetlands Centre are on the same wavelength. Both want to preserve the bay's rich ecology; both want to raise awareness about its precious, unique qualities. Ironically, Tethys and the Wetlands Centre had no idea of each other's existence until a nature lover from Montana happened to visit both. How to get there |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 2 February 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||