|

||

|

Athens Burning |

||

|

A temporary suspension of law and order in the capital was a throw back to the Polytechnic siege of 1973 By John Psaropoulos editor@athensnews.eu

SIX days of rioting last week left much of central Athens in a state of semi-demolition. Two multistorey buildings on Filellinon Avenue off Syntagma Square were torched on the night of December 8, one of them housing Olympic Airways offices on the ground floor. |

||

| and Akadimias streets, and another multi-storey office building on the corner of Akadimias and Hippokratous streets. From Syngrou Avenue to posh Kolonaki, a distance of two kilometres across the centre of town, recycling bins were set aflame, bus stops and phone booths were mauled, and shop, bank and hotel windows were smashed. There were some close calls. A young woman was trapped by fire on the second floor of the foreign ministry's diplomatic training school on the corner of Tsakalof and Dimokritou streets in Kolonaki on the afternoon of December 8. Neighbours had rushed with ladders and brought people down from the first floor, but the woman was threatening to jump. The crowd persuaded her not to and she was brought down by the fire brigade. The worst came after nightfall. Police held a line on Akadimias between a cluster of fire trucks extinguishing the building on the corner of Hippokratous and demonstrators lurking in the pedestrianised street between the Athens University's law building and the National Library next door - both among the capital's gems of Neoclassical architecture. The rioters would emerge to throw pieces of masonry ripped from the cobblestone paving, then retreat. Police mostly held back, but on a few occasions charged to break up the rioters. First blood The riots began on the night of December 6 when a member of the Special Guards - an elite police unit formed to protect high-value targets such as visiting dignitaries, diplomats and politicians - shot and killed 15-year-old Alexandros Grigoropoulos. Angry rioters took to the streets of the famously recalcitrant central neighbourhood of Exarheia, burning rubbish dumpsters and facing down police. According to a police statement released the following day, the officer and his companion had been set upon by a group of 30 youths throwing objects. They got out of their car to make arrests and faced a renewed assault. At that point, one let off a stun grenade, while the other pulled his revolver and fired warning shots, one of which killed the boy, police said. Dora Barkoula, a young doctor working in Evangelismos hospital, was in an apartment block near the scene of the shooting. "I heard three shots. We rushed outside with a friend and saw people gathering," she told English-language Athens International Radio. "When we got to the scene, the boy was lying down. He was covered in blood. I checked for his pulse and found none. He was already dead." Grigoropoulos was bleeding so badly that Barkoula could not locate a wound. "His chest was covered in blood. He had been hit in the chest." When asked whether she heard another noise before, during or after the shots that might corroborate the alleged use of the stun grenade, she said: "No, I just heard three shots. I didn't hear anything else." The ambulance, she said, came in what felt to her like 15 minutes, "but it was already too late!" Students rioting outside the Polytechnic the following night had no doubt that police were lying. "They didn't kill him; they murdered him," said a woman in her early 20s, who gave her name as Maria Karamanou. "I was there. I wasn't part of his group, but I was right next to them." "They [police] took aim at him. The kids were sitting there. The policeman said something to them, and they returned an insult. They didn't throw anything. The cops murdered him," Karamanou said. She contradicted the police report that three shots were fired. "It was a single shot to the heart. That was it." But Karamanou was vague about how far away from the incident she was and how many people formed part of Grigoropoulos' group of friends. None of the rioters interviewed by this newspaper believed the police version. All were convinced that the officer had acted out of malice. Alexandros .Kouyias, a high-profile lawyer who took on the two Special Guards' defence, said the ballistics report showed that the bullet was deformed, lending support to the policeman's story that it ricocheted. Neither the coroner's report nor the ballistics report had been released by the time the Athens News went to press. |

||

The day after, December 11: People walk past burned cars in central Athens, outside Athens Polytechnic and in downtown Athens |

||

Mayhem Karamanou was one of a group of about 250 rioters who held the intersection of Patision and Panepistimiou avenues, just off Omonoia Square on the evening following the shooting. The streets were empty at that point, cleared by an afternoon riot that had seen rioters reach the highly commercial Ermou Street and Syntagma Square. Molotov cocktails had set fires that gutted two Sprider clothing stores, and holes in the plate glass of several shops suggested the use of crowbars. |

||

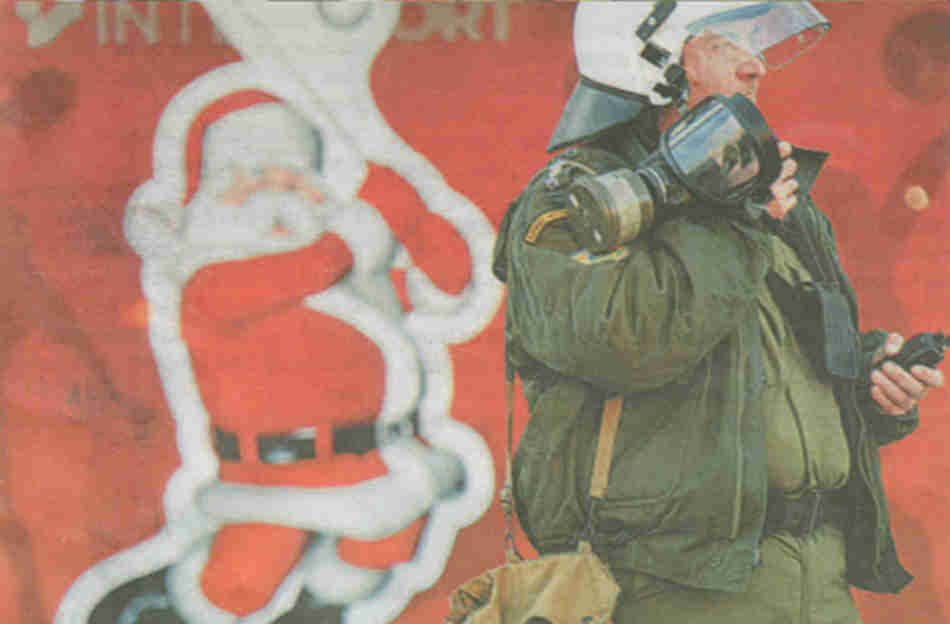

A riot police officer speaks on the radio in Athens on December 9 |

About 20 youths - almost all men - formed the vanguard facing riot police on Patision. Many covered their faces with scarves or hooded tracksuit tops. A few of them dragged a soft-drink refrigerator from the premises of a kiosk, ripped open the sheet metal backing and filled their arms with as many bottles of water and soft drinks cans as they could. They drank a few, but turned most into missiles. Kiosks and cafes that stayed open were never touched, only shuttered businesses. |

|

|

The rioters' aim left much to be desired. Little of what they threw found its way to a riot policeman's plexiglass shield. Most went awfully awry or fell short. But some of the verbal abuse must have hit the mark. "He was 15 years old, you masturbators," said one rioter of Grigoropoulos. "Don't you understand? Do you have shit in your heads?" Another baited, "Do you ever get laid?" And another, "Come on and get your overtime."

Along the fringes of these confrontations of rioters and police, typically 30-50 yards apart, a handful of rioters always worked at the defences of shops. Some break-in attempts were feeble. A rock thrown at a laminated shop window tended to bounce back at the thrower. But elsewhere there were signs of extreme effectiveness, such as crowbars or the butts of fire extinguishers driven into the heart of bank ATMs. Plastic municipal rubbish dumpsters made spectacular tinder and added acrid smoke to the teargas already in the air. At Patision 104, somebody had managed to pry the portcullis of a Germanos electronics store from its rails and smash the thick glass pane behind. Teams of youths plundered the shop, emerging with armfuls of loot and squabbling amongst themselves. Police charges tended to break up the rioters, who were easily spooked. One such charge from Panepistimiou Avenue sent them running across Omonoia Square, where two were taken down on the asphalt like gazelles. One, a girl two of her classmates later identified as Christina, aged 17, shouted at her captors, "I'm a girl, you fool! Do you beat up girls?" The other was Karamanou's husband, Marios, who wrestled several policemen for about 15 minutes. He was eventually cuffed when three policemen sat on top of him. Both these arrests were attended by hysterical screams from rioting companions who, seeing that the predators had made their kills, returned to shout and protest. Enormous confusion surrounded the seizures with rioters, journalists and bystanders being allowed to mingle freely with police. In the confusion, it seemed a simple matter for anyone to pull a policeman's gun from its holster and kill. "I'd like one of you bastards to taste the sweetness of prison for just a month," Marios, a former inmate, shouted as he was marched off to the Omonoia police precinct just off Tritis Septemvriou Avenue. A crowd of about 50 supporters followed. A nervous officer stood outside directing troops not to walk any more prisoners to the precinct as it could bring on an attack. The Polytechnic For most of its length, the six-lane Patision Avenue was littered with broken masonry and concrete on the night of December 7. Students had taken over both the Athens Polytechnic and the Athens University campuses, located about 500 yards apart on the avenue. A healthy bonfire was going just outside the Polytechnic gates, a symbol of resistance to authoritarianism ever since army tanks drove through them on 17 November 1973. That invasion ended a stand-off between students and the military junta then ruling Greece but killed at least two dozen. The gates were left open on December 7, almost as an ostentatious reminder of how unafraid the besieged felt. A couple of dozen hooded youths lingered outside, maintaining pressure on police. One of them, who gave his name as Stavros; agreed to an interview. "If there isn't a reaction to this, what will there be a reaction to?" he said of the Grigoropoulos killing. "As far as I'm concerned, all of Athens should burn. Not average folks making a living, but state targets and banks. And them," he said, pointing to the police. Asked why an underground war between police and anti-authoritarian groups persists in Exarheia, he replied laconically, "Because anarchists don't like cops." The Polytechnic grounds felt like a city under siege. It is a walled compound with a second gate facing Stournara Street, which was closed and guarded. Spontaneous groups had formed to discuss what to do next. One or two fires were kept going. Many students sat alone on benches or walls. In the back of the campus, inside the mess hall, more than a hundred sat on tables, talking and smoking. One small group ripped open a loaf of bread. A student said they had just finished a long assembly to discuss what they would do if the siege went on all night, a discussion obviated by police redeployment. Decentralisation Secondary-school students began to take part in the riots as early as December 7 and they helped decentralise the protests, which often turned disruptive. For instance, on the morning of December 9, more than a hundred 14- to 16year-olds donning colourful backpacks started out from the exclusive southern suburb of Voula and marched along the main coastal artery, Poseidonos Avenue, to neighbouring Glyfada. A single police officer kept traffic about 200 yards behind them. Most marched peacefully, but a handful overturned rubbish dumpsters onto the avenue. The police officer would right the dumpsters and clear the road as best he could so that cars following the procession could pass; but they honked all the same. The demonstrators joined hundreds more secondary-school students already chanting anti-police slogans outside Glyfada police station. They smashed some of its windows and sprayed graffiti on its walls. There were no police in sight and no one ventured out of the building. When asked "Why such an outburst?", 16-year-old Dimitris commented: "Because they [the police] killed a boy, and we want to complain about it. We are angry, very angry." It was the stock argument many secondary-school students gave. |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 22 December 2008 ) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||