|

||

|

Athens to Skopje: 'Enough is Enough' |

||

|

Greece insists it is fully prepared to veto Fyrom's Nato entry if necessary and that a name solution is an issue of national dignity By George Gilson CALL it Nova Makedonija (New Macedonia), or Gorna Makedonija (Upper Macedonia) or Republika Makedonija-Skopje, but never just plain Republic of Macedonia, was Athens' message to Skopje as fresh talks began on November 1 to resolve the name dispute. United Nations mediator Matthew Nimetz called the negotiations in New York. For well over a decade, the two countries have agreed to disagree on what the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (Fyrom) will be called. In that time, over 100 countries have directly or indirectly (in trade agreements etc) recognised Greece's tiny northern neighbour - including the United States in November 2004 - by its constitutional name. |

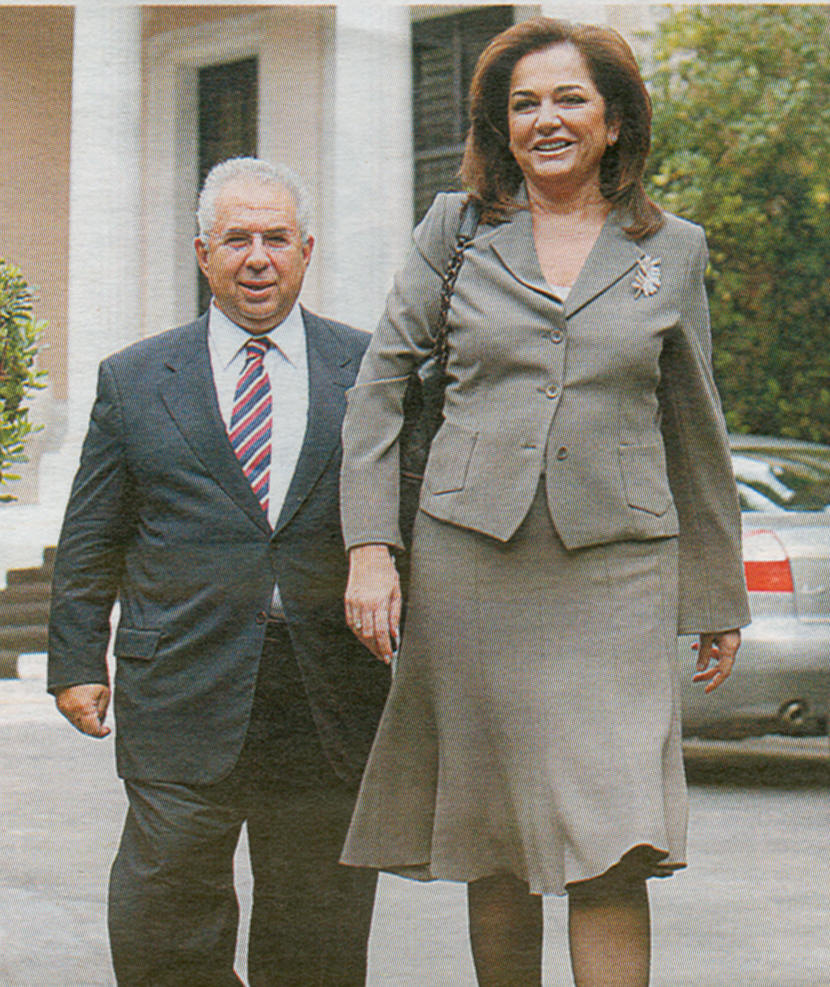

Foreign Minister Dora Bakoyannis and Greece's negotiator in talks with Skopje, retired ambassador Adamantios Vassilakis, leave the prime minister's office after talks with Costas Karamanlis on October 29 |

|

|

The latest position articulated by Foreign Minister Dora Bakoyannis, that Greece will accept a composite name including an adjective designating the geographic part of Macedonia around which the Fyrom state exists, is a major compromise from former Greek positions. In 1992, when all Greek party leaders rejected any name for Fyrom that included the word Macedonia and hundreds of thousands in Thessaloniki were protesting that "Macedonia is Greek", Athens rejected the name "Nova Makedonija". Now, the Greek government would almost certainly embrace such a compromise as a triumph. That is largely because Skopje's tough talk has paid off. The latest talks between Greece and Fyrom came after a barrage of statements and actions by top Fyrom officials rejecting any compromise on the country's constitutional name. Fyrom Foreign Minister Antonio Milososki unleashed demeaning remarks about Athens' position in a much-publicised interview with the Athens daily Eleftheros Typos on October 29, calling a possible Greek veto "the strategy of the irrational loser". "This is not like Coca-Cola trademark, so as to consider whether the name Coca-Cola Light would be acceptable," he said. Milososki suggested that Greece's stance undermines Nato's priority of securing Balkan stability in view of the security challenges posed by Kosovo's final status. Athens insists that a settlement will gain Skopje a strong, valuable ally when the prospeCt of Kosovo independence could work to destabilise Fyrom, with its over one-third Albanian minority. Albanian-majority municipalities fly the Albanian flag rather than Fyrom's six years after an Albanian separatist insurgency brought Fyrom to the edge of the abyss. Prime Minister Costas Karamanlis met with Bakoyannis and Greece's negotiator in talks with Skopje, retired ambassador Adamantios Vassilakis on October 29. Bakoyannis brushed off Milososki's remarks, saying Greece has no need to engage in sharp rhetoric and she suggested that the settlement should come before Nato issues invitations for new members. "I think that when you have patience and persistence you succeed," Vassilakis said. UN mediator Matthew Nimetz is well aware that Greece wants a settlement by April, and Athens is prepared to hold talks at the foreign ministers' level if Nimetz proposes it. Athens has also made clear its determination to veto Fyrom's Nato admission if no agreement is reached. While a 1995 Greece-Fyrom agreement says Greece cannot block Skopje's entry in international organisations as "Fyrom", Athens says it can invoke Fyrom's egregious violation of another article barring, Skopje from engaging in irredentist propaganda against Greece. "We are at a stage where Skopje knows that Greece will act as it says. For years they were reassured by good trade relations with Athens, Now they know that this is a red line," a Greek diplomat says. "We will transform this problem into a Nato problem," he stresses. "Each country has certain red lines when it comes to their national dignity, just as the US and all other countries. We have reached the point where one says 'Enough is enough'," the diplomat says, underlining that agreeing to a special name which only Greece would use for Fyrom is out of the question. "We can't call someone John when everyone else calls him Basil." The Greek foreign ministry also says that about 10 percent of the 123 countries that Fyrom says have recognised it as Republic of Macedonia have not done so formally with a note verbale, but indirectly by signing bilateral trade agreements where Fyrom's constitutional name is used. Athens stresses that a solution of the name dispute will motivate more Greek investment in Fyrom than already. Greek private and public investment in Fyrom has amounted to one billion euros, and accounts for over 20,000 jobs in that country. "Greece has much more to offer this country. But when uncertainty exists, these economic forces are kept back," the Greek diplomatic source says. About 80 percent of Fyrom's population opposes any change to the country's constitutional party, and the ruling nationalist VMRO party plays on that. But about two-thirds of Greeks in three separate polls object to any name for Fyrom that even includes the name Macedonia. The Greek side stresses that this is exactly why it is negotiating towards the aim of agreeing on a composite name. Athens categorically rejects Skopje's position of the last several years that the talks are aimed at deciding only what Greece will call Skopje. And it says this is not an issue of stubbornness, but is intimatelylinked to Skopje's irredentist propaganda. The Greek foreign ministry cites, for example, a 1996 Fyrom law on "scientific and research activities" forbidding studies in that country by any domestic or foreign legal entity or person touching upon "the historical and cultural identity of the Macedonian people" other than ones controlled and financed by the state. "This is a muzzle, a Stalinist law that is perhaps one of the last remnants of communism," the Greek diplomatic source said. Any settlement would have to pass the UN Security Council, which in 1993 asked the two sides to negotiate a settlement, and then be adopted by the UN General Assembly. |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 7 November 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||