|

||

|

Bursa: Pious, Thermal and Carnivorous |

||

|

Despite the impact of industrialisation, the first Ottoman capital and a major silk-weaving centre in Byzantine times, holds on to its romantic charm By Alex Penman I haven't quite figured out what exactly it is that draws me to Bursa, my regular outing to escape Istanbul's havoc. The first Ottomon capital is only a couple of hours away by boat and bus from my Istanbul home, but in every way a different world. |

The imperial tombs in the Muradlye complex, a resting place of the Ottoman sultans |

|

| Even though my staunchly secular Turkish friends abhor its Islamic fervour, they fall prey as much as I do to the timelessness and romantic air of its old quarters. The city lies on the lower slopes of Mount Uludag, the Bithynian Olympus. It evolved, after its fall to the Ottomans, around mosques and imperial tombs, which still radiate piety. Known as a "religious stronghold" second only to Konya the parochial city was transformed over the last twenty years into a major industrial centre, with.a population of more than a million. The impact of industrialisation is apparent: Bursa now appears a concrete city. Its unattractive skyline shouldn't put you off: the city is a repository of Ottoman art, while its forested environs still enchant. On a positive level, industrialisation and the influx of thousands of students and secular Bulgarian Turks has mitigated the conservatism for which Bursa was for centuries renowned. Known to Greeks Prousa, the city was founded by King Prousias of Bithynia in 183 BC. The Romans made it capital of Mysia, attracted by its thermal springs, and built lush public baths. Pliny the Younger mentions a prosperous town with splendid public buildings. In Byzantine times, silk weaving arrived: a famous legend has it that Constantinopolitan monks managed to carry the silk bug out of China hidden in their walking sticks! Proussa silk became celebrated and the city formed part of the Silk Road. The collection of embroidered church drapes in Athens' Benaki Museum demonstrates the skill Proussan workshops acquired. |

||

|

|

Bursa's domes and Ulu Camii seen from the Citadel (Hisar), traditionally the residence of local rulers |

|

|

proclaimed it capital of his state. Early Ottoman Bursa was cosmopolitan and affluent. Alongside the Turks, a large European colony thrived, attracted by the silk and spices trade; many Jews and fewer Greeks and Armenians completed the picture. The Ottoman capital was transferred to Adrianople, captured and renamed Edime in 1369, judged a more appropriate base for conquering the Balkans. Despite the transfer, Bursa retained its importance as a major commercial centre, mainly due to the silk trade. It also continued to command respect as the place were the sultans were buried, a tradition that only ceased after the fall of Constantinople. |

||

Bursa's Ottoman quarters spread on the slopes and hills around the citadel (Hisar), traditionally the residence of local rulers. What was a heavily fortified Acropolis is nowa quiet quarter, offering pleasant panoramas of the city below and the mountain opposite. Concrete constructions have, unfortunately, replaced most Ottoman homes. On the edge of the Hisa (overlooking the city are the mausoleums of Osman, the founder of the Ottoman dynasty, and Orhan, Bursa's conqueror. The tombs, 19th-century reconstructions, occupy the ruins of the Byzantine church of Prophet Elias.Of the latter, some traces of an opus sectile mosaic remain on the floor by Orhan's tomb. The tombs are a sight of pilgrimage during the holy Muslim month of the Ramadan, when busloads of veiled women raid the place - and the rest of the city, for that matter. |

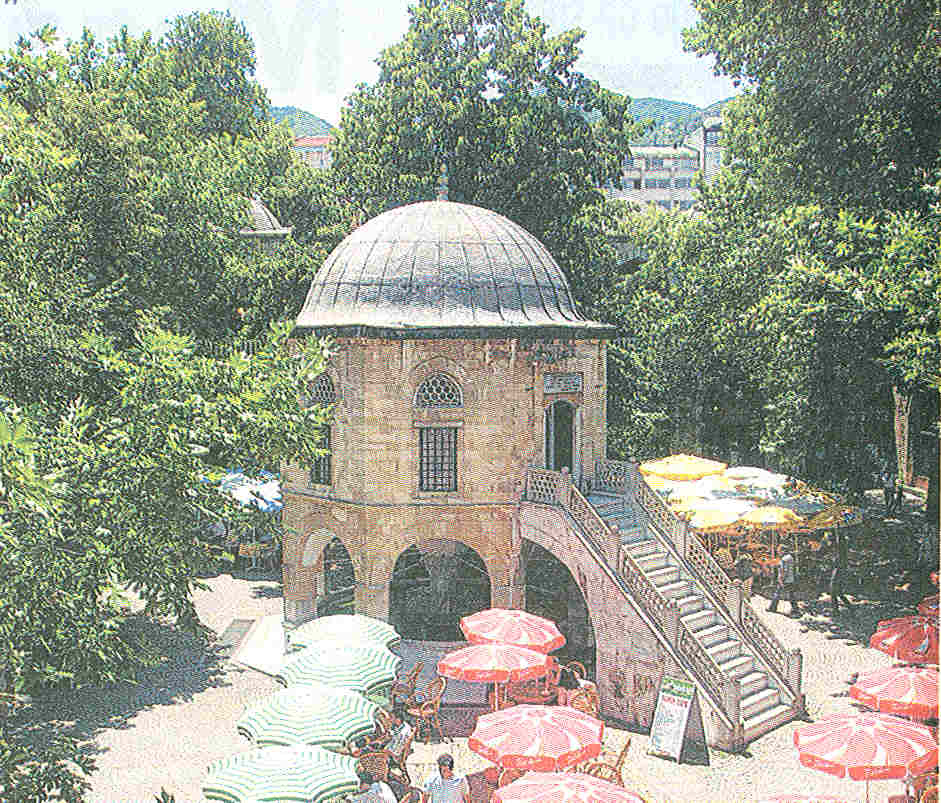

The small mescid (prayer hall) at the centre of Koza Hani, named after the cocoon auction |

|

|

The even older and far more attractive Orhan Gazi Camii (1336) nearby is famously connected with the legend of Karagyoz and Hacivat, two workers in the mosque's construction. With their puns, the pranksters distracted fellow workers so much that construction was delayed. An irate Orhan had them beheaded, but soon repented and devised the art that survives today - camel-leather painted figures in a shadow-theatre also known as Karagyoz, famous in Turkey but also in Greece -to immortalise the couple. |

||

The commercial heart of Ottoman Bursa was Koza Hani (Silk-cocoon Hall), thus named because of the cocoon auction still performed every summer in its main court, around the tiny mescid (prayer room) - an unforgettable spectacle should you happen to pass in late June or early July. Silkworm breeders gather to sell their produce; the cobbled court is filled with bags full of the snow-white cocoons, the most visible remnant of a tradition dating back some fifteen centuries. Until the 1920s, silk weaving was largely in Greek and Armenian hands. Most weaving factories belonged to those two communities and most of the workforce consisted of Christian women. Women were preferred over men as cheap seasonal labour (women were paid less than men, while most also worked in agriculture). A non-Muslim bourgeoisie of Greeks, Armenians and Jews was created with the silk money. |

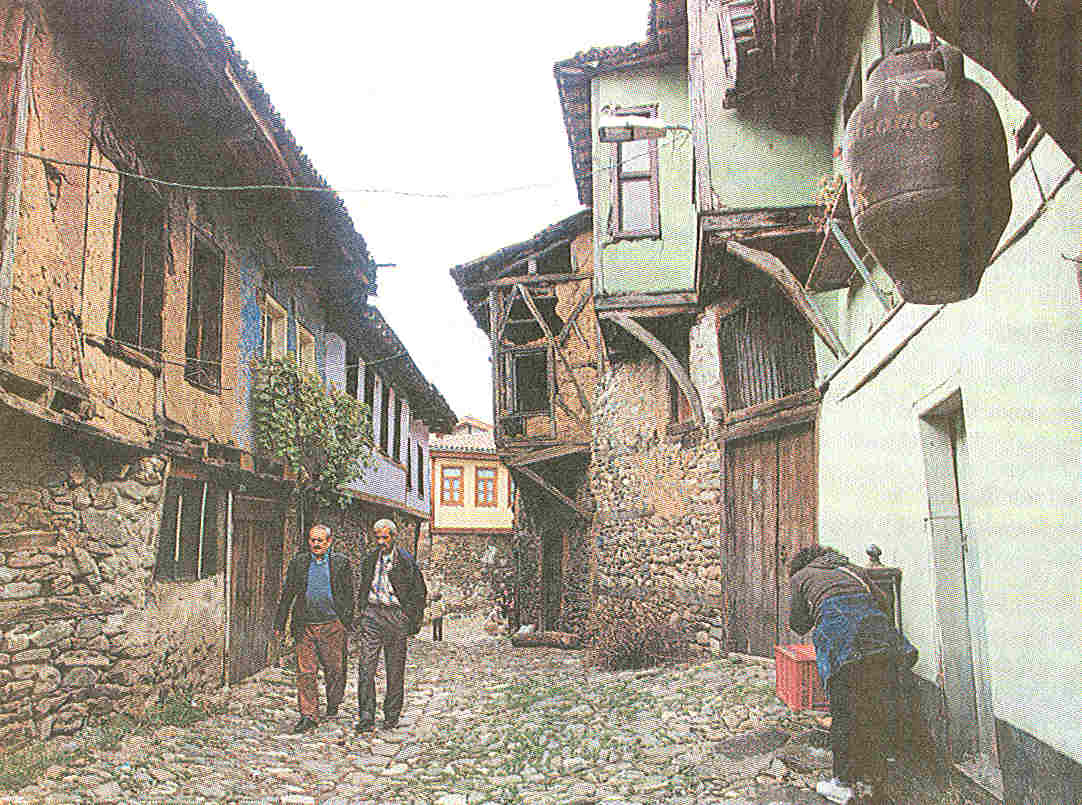

The cobbled streets of the Cumalikizik village |

|

|

I was amazed to notice a large number of transvestites going about in the evening. A foreign friend had once said that Bursa may be the second capital of the religious (centred in Konya), but it is the capital of the transvestite. Just another of Turkey's paradoxes, this uneasy coexistence of zealots and society's often marginalised figures. |

||

Bursa's monumental quarter of Yeshil (Green) is situated beyond scenic Gyok Dere (Heavenly Stream), lined with rustic Ottoman houses. Of its many bridges, the most notable is covered Irgandi Bridge. Built in 1421 by a wealthy philanthropist, the bridge was destroyed by a retreating Greek army in 1922 and was recently restored. On both sides of Gyok Dere stood the Armenian quarter of Setbasi: more than 10,000 Gregorian Armenians and 700 Armenian Catholics lived here before 1915, working in the silk and carpet industries, owning many hammams in nearby Chekirge. Their grand churches survive only in photographs, levelled after the genocide. |

The beautiful arabesque tiles at Yeshil Camii are the work of artisans brought over from Tabriz in Iran |

|

|

I find Yeshil Camii (The Green Mosque) and Yeshil Turbe (The Green Mausoleum) Turkey's most impressive Islamic monuments. The interior of the former, erected in 1413-1424, . is covered with beautiful polychrome tiles, the work of artisans brought over from Tabriz in Iran. Their blue-green texture gives the mosque its name. The ribbed lesser domes are also decorated with beautiful floral patterns in red. One cannot escape noticing the massive Byzantine acanthus capitals decorating the columns of the foyer; above it hides the exquisite imperial lodge. Entry is usually denied, but you'll make your way paying a small tip. If you're lucky, you may reach unnoticed the mihrab (altar), a huge surface covered with Tabriz tiles. (Women shouldn't try). My favourite comer is the Muradiye quarter, stretching around the namesake mosque in the other end of the Old City. The old houses of this quaint, dreamy district are much better kept. Opposite the park containing the tombs of the Ottoman Sultans stand the ruins of the Greek church of Saint George, now incorporated, inside military barracks and guarded. The church, one of the three Greek parishes of Bursa, was a huge stone basilica of impressive line. Its ruins are the most conspicuous remnant of late Ottoman Bursa's 10,000 Greeks. Handed over to the army, it is inaccessible. The cubic forms of the brightly painted houses of the once Greek quarter of Kayabasi surrounding Saint George, follow the Ottoman line. Yet their details - busts of mythological figures, ionic columns, triangular pediments and Greek initials on the doors - betray their Greek past. The only non-Muslim community still present in Bursa is the Sephardic Jews, numbering about 70. Pedestrian Sakarya Street, lined with eateries and bars, was once the main alley of the town's Jewish quarter (Juderva). There has been a Jewish community in town since Byzantine times. Orhan, upon taking the city, issued a permit for a new synagogue, Ets Ha-Khaim, operative until 50 years ago. Today, Guesher on Sakarya St is the larger of two operative synagogues. The keeper, an elderly Jewish merchant, confided that the 70-odd Bursa Jews, the only minority in town, feel extremely apprehensive at the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and the bomb attacks on Istanbul synagogues in 2003. "The young can't wait to leave for Istanbul or abroad. Few attend Sabbath services - the bombs scared people away. Mixed marriages are now common. In a few years, there will be no Jews in Bursa," he lamented. The synagogue was plain, lacking the rustic splendour of those in Istanbul or Izmir. Yet the Torah scrolls were carried over from Spain in the 1492 Sephardic exodus. My evenings in Bursa are always dedicated to strolling in the deserted streets of the Ottoman quarters and to savouring the local cuisine. The latter is firmly set on meat dishes; the fish and hors d'oeuvres dominating Istanbul menus are hard to find. Bursa is firmly carnivorous. Local specialties include Iskender Kebab (lamb kebab or gyros in a butter, tomato and yoghurt sauce with chopped pitta bread), -Inegyol kyofte (a special. kind of meatballs), helva pies and candied chestnuts. The other evening temptation after a long walk up and down the hills of the old quarters is to indulge in one of the city's hammams. Thermal springs still win fame for the city, which - as it has done for the past 22 centuries - puts 'them to good use. The best hammams are to be found in the attractive suburb of Cekirge. By far the most attractive baths are Eski Kaplica. The hammams in the city centre are less lush. Turkish baths have separate sections for men and women. In the former, men must always wrap a special towel round their waist. If you ever find yourself in one where this "modesty rule" is not observed, take it for granted that it is a gay hammam, even though unofficially. Another highlight of Bursa's immediate vicinity is the small village of Cumalikizik, just half an hour from the city in a minibus. The village is one of the best preserved Ottoman villages in the country. Its brightly painted houses and cobbled alleys now provide the setting for television series and movies with a historical setting. The village women and even little girls go about veiled and dogs and hens roam the street. For its magnificent mosques, excellent kebabs and helva pies and the greenery of its surroundings, Bursa will remain my preferred base for exploring the southern shore of the Sea of Marmara, with its Byzantine remains, delightful coastal towns and number of idyllic lakes. My closest escape... How to go From Istanbul by bus and boat (21/2 hours) or plane (15min) Where to stay If luxury is what you're after, try Atlas Termal (Hamamlar St 35, 0090 224 4100 and Celik Palace on Cekirge Caddesi (0090 224 233 3800, both in Cekirge (and do bargain). If you can settle with something modest and prefer to be by the central monuments, try Hotel Cheshmeli (Gumus-Ceken Caddesi 6, 0090 224 1511) or Hotel lpekci at the Bazaar (Cancilar Caddesi 38, - 0090 224 221 19 35) Where and what to eat Kebabci Iskender (Unlu Caddesi 7), whereIskender Kebab was supposedly invented. Uch Kyofte (Ivaz Pasha Charshisi 3) for meatballs. Arap Sukru, a-good fish restaurant in pedestrian and atmospheric Sakarya, one of the few places where alcohol is served |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 21 November 2006) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||