|

Michael J. Reppas, Esq.

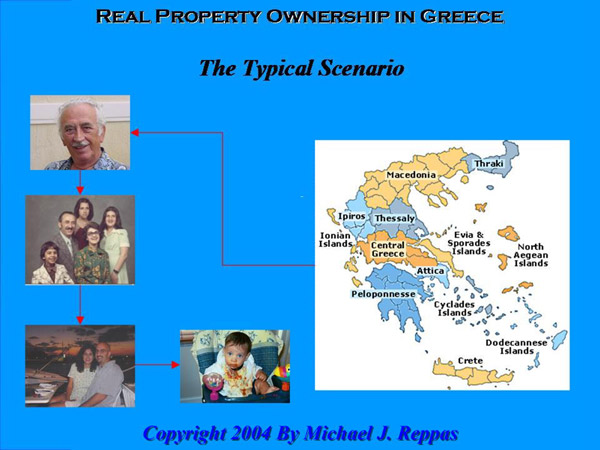

Whatever Happened To Your Family Property In Greece? How do I find out if my family has any claim to the property we left behind in Greece? The simple answer to this begins with determining the “legal status” and “actual status” of the property itself. The “legal status” is, essentially, determining who is registered in the local land registry as being the owner of the property. This is what us American real estate attorneys find out within a few hours by having a title search run on the property in question. In Greece, however, this determination must be made in person by a knowledgeable person (usually an attorney) who must travel to the local land registry where the property lies and do whatever is necessary to get her way into the records department and look up the information. Sometimes this is a difficult process. The next step is to determine what the “actual status” of the property is. The “actual status” is accomplished by a physical examination of the property to determine who occupies the premises, who claims to be the owner, and what improvements have been made to the property. Once you know who the owner is on the books and who holds himself out to be the owner (which, often times is not the same person), then you need to determine where your claim fits in. Perhaps, the most important rule to know about Greek law is that a person who does not have title to a piece of property but who “takes over” the property for 20 years uninterrupted will likely be considered the legal owner of the property. This is what is called “adverse possession.” So if no one challenges this person’s claim to be the owner, outs him from the property before the twenty years run, or gets rent from him during the 20 years, the claim may be forever lost. As with every law, however, and as every good lawyer knows, there are many exceptions to this rule, but the general rule nonetheless is 20 years. What do I do once I have a legitimate claim to Real Property in Greece? For the sake of brevity now, let me fast forward to a situation where one can show he or she still has a claim to real property in Greece. The person will need to then take a few steps with the legal authorities to register as the legal owner, the Greeks call it “accepting” ownership, will have to pay taxes based on the value of the property, and will have to pay inheritance taxes, if applicable. Once you are the owner, you then have some choices to make. You can either keep the property as the summer home everyone on your block will be envious of, or you can sell the property. Should you elect to sell, you will need to have the right connections to identify a fair market value for the property, find a buyer and close the transaction, and then transfer the funds to the U.S. (where Uncle Sam will be waiting with open hands for his cut). The acquiring and selling of real property in Greece is a difficult business. As those of us who practice this area of law can attest, there are many twists and turns that you have to be able to navigate confidently through in order to resolve these types of matters. But the most important message I can send to you is that if you don’t look into it, you’ll never know. In a world where the language and customs of Greece is a dying tradition for Second and Third generation descendants, maintaining property ownership has to be considered of paramount importance. We have a duty to keep the bridges to our past open, and we cannot let our fears or our lack of knowledge about Greek law stop us from even inquiring into what our rights are. For many, the result will be a pleasant and probably unexpected end. For everyone else, at least you will finally be able to sleep at night and stop wondering “Could I have taken back that property in Greece.”

|

|

MICHAEL J. REPPAS II, practices law in Miami, Florida with a focus on international law, commercial litigation, and the recovery of real estate and property in Greece. He received his LL.M. in International Law from the University of Miami School of Law, his Juris Doctor from St. Thomas School of Law, and his Bachelor of Arts from The Ohio State University.

Mr. Reppas has published numerous articles in newspapers, magazines and in academic journals throughout North America. One of his legal articles, entitled "The Deflowering of the Parthenon: A Legal and Moral Analysis on Why the 'Elgin Marbles' Must Be Returned To Greece," was published in Fordham's prestigious Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal. He also published another significant legal article entitled "The Lawfulness of Humanitarian Intervention," with St. Thomas' Law Review. Reppas has lectured extensively on Greek issues, including being a featured presenter at several AHEPA supreme conventions, International Conferences, as well as in numerous lectures to groups including the Explorer's Club and a plethora of Greek Churches and Greek organizations.

MICHAEL J. REPPAS II, practices law in Miami, Florida with a focus on international law, commercial litigation, and the recovery of real estate and property in Greece. He received his LL.M. in International Law from the University of Miami School of Law, his Juris Doctor from St. Thomas School of Law, and his Bachelor of Arts from The Ohio State University.

Mr. Reppas has published numerous articles in newspapers, magazines and in academic journals throughout North America. One of his legal articles, entitled "The Deflowering of the Parthenon: A Legal and Moral Analysis on Why the 'Elgin Marbles' Must Be Returned To Greece," was published in Fordham's prestigious Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal. He also published another significant legal article entitled "The Lawfulness of Humanitarian Intervention," with St. Thomas' Law Review. Reppas has lectured extensively on Greek issues, including being a featured presenter at several AHEPA supreme conventions, International Conferences, as well as in numerous lectures to groups including the Explorer's Club and a plethora of Greek Churches and Greek organizations.