|

|

|

The Flag of Thyatira A Piece of Anatolia History has Come Home to Anatolia - Where it had Never Been Seen Before |

|

| It is an American flag bearing fourteen stars on a blue field, attached to six white and seven red strips of light wool cloth, with a cord to tie it to a pole. The stitching bears marks of haste. The colors are somewhat faded and moths have chewed holes in some of the stripes. This is a flag with a story - and it came with a storyteller. The flag is the gift of Dr. Constance Cryer Ecklund, Professor of French at Southern Connecticut State University, and the granddaughter of Christo Theologos Papadopoulos, an Anatolia |

From (L) to (R): Consul Elayne Paplos, Constance Ecklund, President Jackson |

|

graduate of the class of 1893. Having decided that the flag should come to Anatolia, she presented it to President Jackson in the presence of the U.S. Consul for Thessaloniki, Elayne Paplos, and other guests on June 7 in the President's office. But before she did so, she told its story. One of the aims of Anatolia College was to train "native laborers," that is, non-American evangelical ministers who would preach the Gospel and establish schools in cities and towns throughout Asia Minor, ministering chiefly to the Armenian and Greek Christian populations. After ordination, the Rev. Papadopoulos and his wife were sent to Ak Hissar (the Biblical Thyatira, where St. Paul had preached) in what is now Western Turkey. |

|

| But the storm clouds that had been gathering over the Armenian population of Asia Minor broke out in massacres in Sasun in 1894 and in Constantinople on September 30, 1895. Three days later, on October 3, the Sultan's troops rode into Ak Hissar, beginning their killing in the town's marketplace. Turkish friends of Rev. Papadopoulos had warned him of their coming. He summoned his

parishioners to come and hide in his school. He directed Erasmia and her two sisters to sew an American flag out of any red, white, and blue cloth available, including the shirt off his own back. Christo and the three women

|

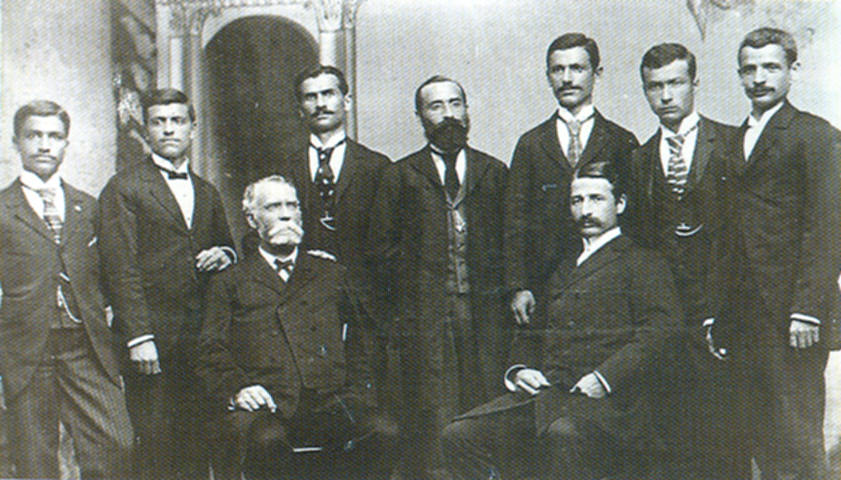

The Anatolia College Class of 1893. Christo Papadopoulos is Standing at the Center |

|

worked all night long. By daybreak they had sewn a flag. What it lacked in stars it made up for in size and prestige. After also serving the Christian communities in Fatsa, Ordu, and Samsun on the Black Sea coast, Rev. Papadopoulos and his family emigrated to America in 1906-07, settling in Chicago, where he ministered to the city's immigrants. The flag went along with them and was often taken out and displayed at family gatherings. Rev. Christo Papadopoulos died in 1922, Erasmia in 1942. The flag passed to a daughter and was forgotten as the family began to lose touch with its history. At one point it was thought to have been thrown away, only to be discovered in an attic some years later and given to Dr. Ecklund, the sole grandchild, who was then trying to recover her family's heritage. She wanted to find a safe place for the flag, and a place where it would be understood. She chose the school that had given her grandfather his vocation - the place that had been his spiritual home, now located in the country of his ancestors - and the flag is now on permanent display at Anatolia. The story has a second act, and that is Dr. Ecklund's own. When she came to Anatolia to present the flag, she was also on a quest for further information about her grandfather, whom she had never known. She was not disappointed. In the school archives she found his name as it was written in Anatolia's enrollment book, along with his class picture. Reading through the Missionary Herald for those years in the Eleftheriades Library she came across accounts by Riggs and former Anatolia President George White that mentioned her grandfather by name. She traveled on to Turkey and to the places where Christo Papadopoulos had lived and worked, and to his alma mater, the now sadly dilapidated former Anatolia campus in Merzifon. ln October she returned to Anatolia as a Dukakis Fellow, doing further research and giving a series of illustrated talks on the flag and its meaning for students at ACT, the I.B. Program, and Anatolia's junior and senior high schools. She urged students to learn their own family histories, and she praised the power of memory - and cloth. "It was cloth against terror," she said, "in the form of a flag raised by an Anatolian who put the lives of others before his own, one night and morning in 1895." |

|

|

(Posting date 3 January 2008) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|