|

||

|

Greeks Going East |

||

|

The Greeks' artistic debts to the east are well documented; less well-known is how pervasively Greek art travelled to India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and even China, helping to shape the Han dynasty's stylised dragon JOHN BOARDMAN* THE GREEKS probably came from the east, Anatolia, in the first place - and they never ignored the other coast of the Aegean Sea, whether you believe there was a Trojan War or not. |

A Greek ketos, or sea monster, on the saddle cloth of a war elephant on a gilt silver disc from central Asia |

|

|

Macedonian rule and made a new Greek kingdom in Bactria, on and around the River Oxus. They created what amounted to a whole new Greek state, in touch still with the homeland, building cities which compromised between the east and Greece.

These Indo-Greeks moved on south, even into northwest India, modern Pakistan, which had been becoming Buddhist. One Greek king became a Buddhist sage, and the Indo-Greeks even made one daring raid across north India to the great city of Patna, some 500 miles beyond Delhi. Greek arts informed the Buddhist arts of the area. A clay figure of an attendant of the Buddha in east Afghanistan is to all intents a pure 4th-century Greek Herakles and only his club has been replaced - by a thunderbolt - for his new function as Vajrapani, the Buddha's guard and attendant. |

||

|

We even find a representation of the Trojan Horse entering Troy, guarded by a highly oriental version of Cassandra. And the first image of the Buddha we have is on a coin of classical type and labelled, in Greek letters, BODDO. In the 2nd century BC, northern Afghanistan had been taken over by a nomad people, who had been moved west from the borders of China - the Yueh-chi or Ru-zhi. Once the Chinese Han dynasty got the better of the nomads, they pressed south the Greeks on the Oxus, and the succession of the so-called Indo-Greek kings can be traced mainly through their coinage and art, from the 2nd century BC even into the 1st century AD in north India. The relics of these Yueh-chi near the Oxus are pieces of relief gold jewellery from six burials excavated by Russian archaeologists in 1978 at the site of Tillya Tepe, which lies just south of the Oxus River in northern Afghanistan, west of the great city of Balkh (Bactra). They date somewhere just before the mid-1st century AD. The gold and the brilliance is distracting, and I soon found it best to redraw figures from the photographs, thus forcing myself to understand each part and not make assumptions about identity and detail from a quick glance or the descriptions of others. As time passed and the pencil drawings accumulated, the focus of interest was sometimes shifted away from being purely Greek towards even China and India. There are interregna of Parthians here and of the Saka (Scythians), all gone by the mid-1st century AD, by which time one of the tribes of the Yueh-chi from Bactria had moved south and, at the time of our gold, were founding the Kushan dynasty. The Kushans were to rule north India (partly Pakistan now) for three centuries. Back in the 5th century, Euripides knew of the god Dionysos' visit to Bactria, where Greeks deported by the Persian king were living - and no doubt making wine - in an area long associated with festive agriculture and behaviour, remarked even by Indian writers in the Mahabharata. But you will find no exact parallel in Greek art for Dionysos and Ariadne sitting on a lion. |

||

| The lion has a leafy beard, a common feature introduced to Central Asian animals by Greek art - call it acanthoid - and a mane like a Greek griffin. The artist of this, or its model, was at home with the Hellenistic iconography of Dionysos and Ariadne and made a confection in keeping with his eastern home, where lion-riders are not uncommon in art and in India may even be a goddess, Nana.

Little details like this reveal the almost living Greekness apparent still in the iconography, no less apparent in much else from the site, even in decorative detail.

An ornament discovered in Tillya Tepe shows an almost pure Aphrodite. But she is a little odd - she has wings and what we would call a caste mark on her forehead. This urna was a sign of importance or divinity, which seems to have originated in Central Asia and was soon to be applied to the figure of the Buddha and others once Greek art had persuaded the east that their man-god deserved an image in the likeness of a Greek god. |

An Aphrodite from the city of Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan demonstrates the reach of Greek forms |

|

|

There are Aphrodites on plaques like these at Taxila, the city laid out first by Indo-Greeks in what is now north Pakistan, then briefly occupied by the Saka and Parthians, then the Greeks again and then the Kushans.

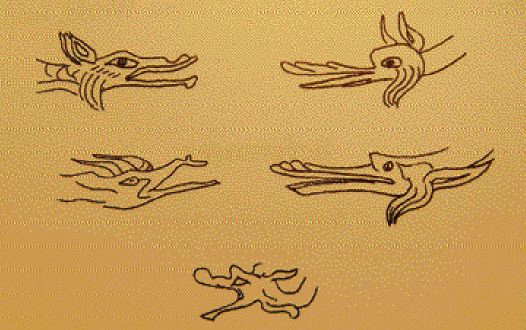

The ketos travels east By the 3rd century BC, Indian art had acquired the makara monster - a bit like a big fish with predatory jaws, sometimes with a flipper, sometimes even two or four short legs. It had a bit of the crocodile about it, and over the years it changes its form, no little influenced at first by the Greek sea monster ketos and eventually having even an elephant head. But this is not a creature brought into India from the north, like the caste mark or the Triton, but homegrown and here affecting the art of a people of the Oxus, whose association with India by this date is historically demonstrated. A lavish but bewildering animal decoration on a fine sword and scabbard from Tillya Tepe may explain why some identities have gone unremarked. Distinctive features are the upturned snout, louring forehead, horn, pricked ears, acanthoid beard, long sinuous body, little wings and the hindquarters twisted so that they are seen from above, splaying the legs to either side. All these features are exactly those of the Chinese dragon of the Han dynasty and belong nowhere else. The second drawing is of a simpler version of the same beast on a gold plaque, which is also from Tillya Tepe. Then, below at the left, a Han Chinese dragon head finial, exactly like the heads of our monsters. These figures are very difficult indeed to see properly in the original and have to be disentangled from their frames and background, as in these drawings. The splayed hindquarters of the dragon betray the fact that by this date, and whatever its origins, the dragon is a more reptilian creature than anything; this is how you see a lizard, not a tiger, from above, not the side, and it will be regular for the Chinese dragons for centuries to come, since they gradually shed their mammalian features that derived from tigers or the like. In its origins, the dragon in China owed something to the arts of nomads to the west, even perhaps to the Huns of Mongolia in early days when it had a wolf-like head, and so was not an altogether foreign concept, though its reptilian features were. |

||

It was a matter of artists being called upon to find an image for what was no more than a word for an important monster; a parallel situation to Greeks looking in Near Eastern art for images to serve their sphinx or siren or chimaera. By now I rather suspect that the Greek sea monster ketos itself made some contribution to dragon iconography hereabouts; it was certainly known in the arts of Central Asia and India. One example is drawn on the saddle cloth of a war elephant on a gilt silver disc from central Asia, controlled by Greeks. If you compare the distinctive profiles of the heads of a Greek ketos and a Han Chinese dragon, you may well be led to think that the comparison has some force, recalling that the Greek was invented 200 years before this version of the Chinese. |

Various renditions of the Greek ketos (R), copied in pencil by the author, and of the Chinese dragon (L) |

|

Can you tell the difference? The Greek are on the right, the Chinese on the left, and below is one from Tillya Tepe. The Han artists perfected the dragon form for centuries to come and it played a major role in Chinese art and thought, while the Greek ketos became the whale that swallowed Jonah in western art. Add to this chinoiserie the fact that three of the Tillya Tepe tombs contain Chinese mirrors, and we can see that the Yueh-chi's links with the east and their old homelands were not forgotten, any more than the fact that they were in territory long - and perhaps to some degree still - occupied by Greeks. A Greek princess in Afghanistan? There were six burials at Tillya Tepe, thankfully found unlooted by archaeologists. Five were of women, one of a man. The sensible suggestion has been made that they are all of one period, probably the middle of the first century, even though among the finds are small items that went back centuries - one was a Greco-Persian scaraboid of the 5th/4th century BC. This was not a people that was yet much bothered with coinage. They were heavily under the influence of their predecessors, many still in residence, who were Greek. The Kushans had just started minting coins, and one was found in one of the burials - just possibly minted by the first Kushan king - and locally in the north. The finds were carefully recorded and it proved possible for the excavator Victor Sarianidi, appropriately a Russian-Greek, to make plausible reconstructions of dress for each body. Recent, closer study of this has found close parallels with the dress of early Kushans in India. I would like to dwell on one of the ladies, whom we know only as Burial 6. She had the distinction of wearing a fine Asian tree crown of gold, but the rest of her jewellery stands out from the rest, not for its lavishness - they were all lavish - but for its choice of subjects. She had almost a monopoly, certainly the lion's share, of the most Greek subjects - the Dionysos and Ariadne on lion plaques, two of the Aphrodites. She was the only one wearing earrings in the form of an Eros, a type well diffused in the east by this date. She was the only one to have coloured glass cosmetic jugs from the Mediterranean world, from Syria, in her grave. On her hand she wore a finger ring with the intaglio of a classical Greek head. In her hand she held a gold Parthian coin. In her mouth she had a silver Parthian coin, but in its latest use was counter-struck with the helmeted head of a Bactrian Greek ruler. The coins in hand and in mouth are, of course, the Greek custom of supplying Charon's fee for the journey over the River Styx, otherwise attested in the east in later years for other peoples. So was Burial 6 an Indo-Greek princess? The Scythian king of Taxila, Maues, had a son with a Greek name, Artemidoros, so one of his wives was probably an Indo-Greek. Inter-marriage between the old and new royal houses must have been common. Alexander had his Roxane. Was the king buried at Tillya Tepe taken by a late and expatriate expression of Hellenic physique and grace? I would like to think so, if only to get away for a moment from dragons and the like and to recall that pervasiveness of the Greeks, even through all Asia, which makes study of their history and arts so very rewarding. *The author is emeritus professor of classical art and archaeology at Oxford. This article is an abbreviated version of the lecture he delivered at this year's annual presentation of excavations by the British School at Athens |

||

(Posting date 2 October 2008)

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||