|

||

|

Lia: Epirus' Famous Hamlet By Diana Farr Louis |

||

|

Owing much of its reputation to the international bestseller 'Eleni', theremote village is revisited in a book by Eleni's granddaughter that chroniclesher mission to rebuild her grandmother's house

|

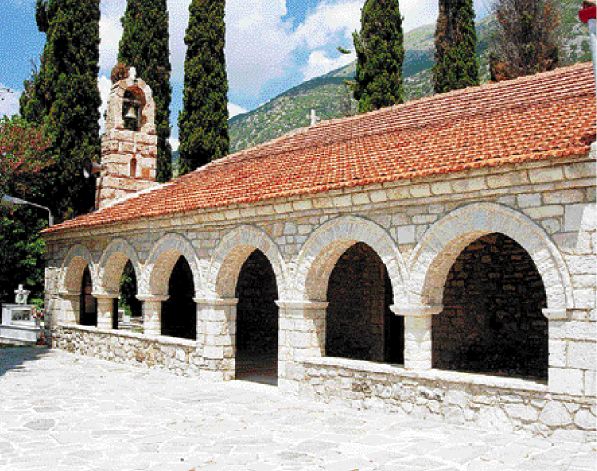

The church nearest Eleni's house has a new roof and loudspeakers attached so the whole village can hear the service whether they want it or not |

|

Though beautiful, the scenery here lacks the drama of the Vikos Gorge, while the village possesses neither the boutique hotels nor traditional tavernas of the Zagorohoria. It does not even have the spacious plateia sheltered by a humongous plane tree that is the trademark of most Epirot villages from Metsovo to Syrrako. What Lia does have, however, is a reputation, some might say a notoriety, because of the dire things that happened here in the late 1940s during the Greek civil war. |

||

Dreadful events tore apart much of the country as Communists tried to drag Greece behind the Iron Curtain, and Nationalist forces fought to keep it in the West. |

||

|

No doubt both sides were guilty of atrocities and certainly Lia had no monopoly on them. But this is the village that Nicholas Gage made famous with his portrayal of his mother Eleni's ordeal to save her children from being wrenched away from Lia and marched across the border into Albania and Yugoslavia. Published in 1983, Eleni was an international bestseller that here in Greece reopened the divisions between Left and Right about those years. Not only did it paint an unequivocally evil portrait of Communist brutality, it was also an indictment of the petty and 'primitive' behaviour that simmers just below the surface in small communities everywhere. As a detective story about a son's quest to find his mother's killers, it is a page turner and as a portrait of Gage's unusually strong, intelligent and loving mother, it is unforgettable. |

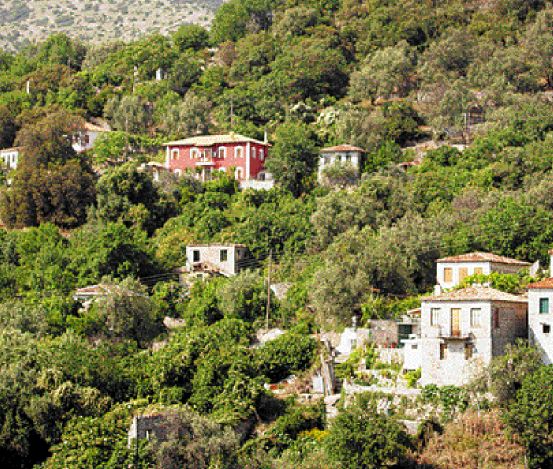

In spring Lia is almost hidden under thick foliage. Behind it rise the bleak Mourgana mountains which mark the boundry with Albania |

|

| Before Eleni, Lia (named after its patron the Prophet Elijah - Elias in Greek) might never have seen a foreign tourist. Like so many mountain settlements, it lost its young people to cities in Greece and abroad, and its position high up in the inhospitable Mourgana range made it uncomfortably close to Albania. But soon curious readers began to trickle in and Gage (born Gatzoyiannis) helped the village to build a hotel for them, Lias Inn, at the entrance to town. Drawn by a similar fascination, I paid Lia a visit last summer. It is so isolated that fifty years ago little Nicholas had never seen a car until he and his sisters escaped to the port of Igoumenitsa (and eventually to Massachusetts). But it is only about a two hour's drive northwest of Ioannina. We stopped at the hotel to get our bearings and were given a hand-drawn map showing all the landmarks in Gage's book: his mother's home, grandfather's home, churches, homes of friends, escape route and even the execution site way up the mountain near the Prophet's chapel. Eleni had become a cottage industry. |

||

Despite signs of modern prosperity - a Rover outside a fancy gate, brand new red tile roofs, megaphones on the church walls - Lia seemed empty and somewhat morose. We felt oppressed in the drab cafe with its indifferent service, depressed by the empty space in front of the hotel, which could have been a charming place to sit on a lovely June day. But to many other visitors it has been a source of inspiration. Leafing through the hotel's guest book, I read tribute after emotional tribute to Eleni's courage and motherly love from people round the world. "So who comes here?" I asked Niki, who runs the hotel with her husband Fanis. "Dutch, Germans, a few Greeks with ties here, and journalists," she replied. Then she showed me the second Gage book about Lia, North of Ithaka by Eleni Gage, Nicholas's twenty-eight-year-old daughter, which had just appeared in Greek translation. |

Eleni's house - the largest one in Lia before the war - stands peacefully, hardly the scene of so many tragic memories. Inset: A plaque set into the wall of the house commemorates its original foundations, extension and restoration |

|

|

A journalist like her father, Eleni decided to interrupt her New York career of writing for women's magazines with the side benefit of "all the free makeup a girl could ever want" and move to Lia for a year. Her mission: to rebuild her grandmother's house. This was no small undertaking. Quite apart from all the construction problems involved in restoring a ruin, there was an unusually high quotient of emotional issues to resolve. First of all, her four aunts - the thitsas - opposed meddling with the past. They remembered their mother's curse. Before their escape, she had fiercely told them to throw a black stone over their shoulders and vow never to return to live in Greece. Or else. Besides they were afraid of unearthing so much pain. After all, the Communists had taken over their house and imprisoned 31 people in its basement and buried another 37 in the garden. Eleni was also very apprehensive about how the villagers would view her project. Would it bring up long-buried divisions? Would they resent a foreigner rummaging around in their memories? Whatever her qualms, her desire to turn the wreck into a home proved stronger. Eleni Gage's chronicle of her year in Lia makes entertaining reading. She brings to it a deft, light touch, introducing us to numerous village characters (whose average age is well over 60), weaving comic tales about the rebuilding saga with local festivals and customs, trips to Epirot landmarks such as Metsovo and the Oracle of the Dead and into Albania, insights into key cultural differences between the urban US and rural Greece, and stories from the past, happy and tragic. Before Eleni embarked on her project, she had never dared to read her father's book. Naturally she had heard all the stories - about her grandmother's marriage to a supposedly rich Americanos. He was an emigrant who came back from the States every few years, long enough to father a child and fill her house with luxuries, such as the only bed in the village. She also knew that having the largest house in Lia provoked resentment in some neighbours and that during Eleni senior's last years she had had little contact or assistance from her husband because of the war. But she had shielded herself from the details of her grandmother's imprisonment and execution. As the house begins to emerge from the rubble, however, artefacts surface from its inhabitants' daily life which shed new light on their existence. The first is a Turkish coin dated 1856, which more distant ancestors had placed in the foundations of the house "to give it strength". It is followed by spoons, an inkwell, medicine bottles and the iron bedstead itself, flattened by a huge rock. And as more and more shreds of the past are discovered, Eleni starts "to consider my grandmother's life more than her death". At the same time, she is constantly learning about herself and about the village - "a cross between a gentlemen's club and a retirement home" in a reversal of the prewar situation when women far outnumbered their men who were invariably away earning money. Though living in one of the poorest regions in the EU, these old people seem far less desperate than the bag ladies of New York. And while they may have been "overly cursed with tragedy, they [are] blessed with an acute ability to enjoy life's small pleasures". With all the saints days and holidays, Lia becomes host to "a non-stop party". In turn, Eleni herself finds herself abandoning her New Yorker's "avoidance reflex", the pose of indifference one adopts in that city (which is also mine) in the interests of self-preservation. She finds that "Greece is not for spectators... in the University of Life 90 percent of your grade is participation" (whether you're trying to park on a crowded street or arguing politics). "Once in Greece, I quickly realised there were no sidelines for me to stand on any more... With so many of my days devoted to excavating my family's past, I sought out any distraction that didn't have to do with my history. Luckily, the most important events required no preparation."

Eager to fit in, Eleni "is swept up" into group activities like Carnival and Easter week, traditional superstitions like reading coffee grounds or casting out the evil eye, and a large number of funerals - to be expected in a village populated by so many grandparents. She admires the Greeks' relationship with death where it is "regarded as rather like the postman: a frequent visitor who has a job to do" as opposed to the Americans' tendency to view it as a "spectre that lurks in books and movies."

Because she is half-Greek (Eleni's mother Joanie is a non-hyphenated American) and fluent in the language, Eleni does not fall into the traps that mar so many books written about this country. She is neither cute nor condescending. Her characters are real, rounded people rather than stereotypes or caricatures and she writes about them with unsentimental affection. Her approach to history and religious customs is entertaining and accurate. And she also has a good ear for dialogue. Aunt Kanta's Greeklish (which instead of making her an outsider in both cultures seems to enable her to belong everywhere), her Albanian builders' pidgin Greek, and any number of conversations with villagers, Athenians or American friends and relatives enrich the book with many distinct voices. Eleni confesses that she feels it is her role to "amuse everyone... provide the regional punchline" with her Americanisms. In her writing, these same colloquialisms and levity may be occasionally irritating to English speakers of a different background. Nevertheless, they provide definite relief from the darker themes touched on. In the end, North of Ithaka - Eleni's personal odyssey - is a tale of reconciliation and acceptance. In one very moving episode as the house nears completion, Thitsa Kanta, who was the most opposed to the project, hears her mother calling in a dream. She says she's tired because she has been looking after the girl (i kopela) and to paidi (Nicholas, still her little boy), rescuing them from near fatal car accidents. With Kanta in Lia, she can relax. The next scene shows Kanta conducting some German tourists around the building site, brimming with pride. But she is not alone. When the housewarming party finally occurs on St Nicholas Day in early December, the whole village turns up - all 50 inhabitants - some of them bearing "specially chosen gifts... [they] didn't hold its tragic past against the house, but welcomed it as they had me, and wanted to embellish the interior with bits of their own past." When Father Prokopi blesses the basement, Eleni feels relief wash over her. "I still shuddered at the thought of my grandmother's pain, but no longer felt it was trapped here within these walls." In North of Ithaka, Eleni Gage has brought Lia up to date. By laying ghosts to rest, revealing its citizens' personalities and depicting its customs with humour and warmth, she has freed it from the prison of the past. By recasting its reputation, she has given Lia the right to exist as just another pretty mountain village. I only wish I had read the book before I visited. Photos by Diana Farr Louis Getting there Lia can be reached from either Ioannina or Igoumenitsa. Take the main road between them and turn north at Vrosina. The road is marked green for scenic on the map. You'll notice that the border between Greece and Albania dips substantially into the latter just above Lia. This is allegedly the result of a little bribe from a local to the German official in charge of dividing Epirus in two after WWI Where to stay and eat |

||

|

Eleni Gage's North of Ithaka was published by Bantam Books in 2004 and in paperback in 2005 |

|

(Posting date 27 April 2006) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||