|

|

|

May 29, 1453: The Fall of Constantinople |

|

|

When, at the age of twenty-one, Mehmed II (1451-1481) sat on the throne of the Ottoman Sultans his first thoughts turned to Constantinople. The capital was all that was left from the mighty Christian Roman Empire and its presence, in the midst of the dominions of the powerful new rulers of the lands of Romania, was pregnant with danger. The new Sultan demonstrated diplomatic abilities, during his early attempts to isolate politically the Byzantine capital, when he signed treaties with the Emperor's most important Western allies, the Hungarians and the Venetians. He knew, however, that these were temporary measures, which would provide him with freedom of movement for a limited time only. |

Artist's depiction of Constantine Paleologos inside the land walls of the City uder seige. |

|

|

|

| Help was limited. Indeed, under the command of the brave Giovanni Giustiniani Longo about 700 well armed men sailed, on two Genoese vessels, for the Byzantine capital. The ships arrived in the city on January 29, 1453, Giustiniani was promptly appointed by the Emperor head of the defense. Of the men, 400 were recruited in Genoa and 300 on the Genoese held island of Chios. Giustiniani's men composed the largest Western contingent. Also, Venice allowed the Emperor to recruit a contingent of Cretan soldiers and sailors, who acted heroically during the siege. The former |

|

|

Metropolitan of Kiev and All Russia Isidoros, a Cardinal of the Roman Church, who came to Constantinople as Papal Legate, recruited at Naples, at the Pope's expense, 200 soldiers. A number of brave men joined the Emperor in his final stand: Maurizio Cattaneo, the Bocchiardo brothers, Paolo, Antonio and Troilo, the Castilian nobleman Don Francisco de Toledo, the German engineer Johannes Grant, and also the Ottoman prince Orhan, who lived in Constantinople. |

|

|

|

|

|

Despite the official document and the Emperor's willingness to implement it, the end could not be avoided. The agreement was seen by the people, back home, as submission to the Papacy and betrayal of the Orthodox faith. The promised crusade, to save Constantinople, collapsed on the battlefield of Varna, in Bulgaria, on November 10, 1444. Four years later, on October 31, 1448, John VIII, depressed and disillusioned, passed away. As he had no children the imperial crown passed on to his brother Constantine, who was, at the time, ruler of the Peloponnese, the Despotato of Moreas. Crowned in the Cathedral at Mystra, his capital, on January 6, 1449, the new and last Christian Roman Emperor entered, two months later, on March 12, the isolated Imperial capital. Behind the ancient walls of Constantinople the new Emperor followed his late brother's policies; He could not do much else. Thus, amid hostile reactions by most of the city's population, he attempted to revive the Union (with the Papal Church) by proclaiming it in the Cathedral of Saint Sophia on December 12, 1452. No practical results came out of the enforced proclamation. Despite Constantine's final appeals to the Pope and to his Western allies, no crusade and no substantial help ever materialized. Promises and expressions of sympathy were all that was sent to him, and in any case he did not live long enough to receive them. As a matter of fact, in the middle of May of 1453 the Venetian Senate was still deliberatingabout sending a fleet to Constantinople. Even the Genoese colony of Pera, facing the capital, attempted to stay neutral. It did, but neutrality did not help it when the Sultan succeeded the Roman Emperors. To the people of the capital, the only thing that mattered now, at the end of political freedom and at the beginning of the long darkness of foreign occupation, was holding on to the ancestral faith.

|

|

|

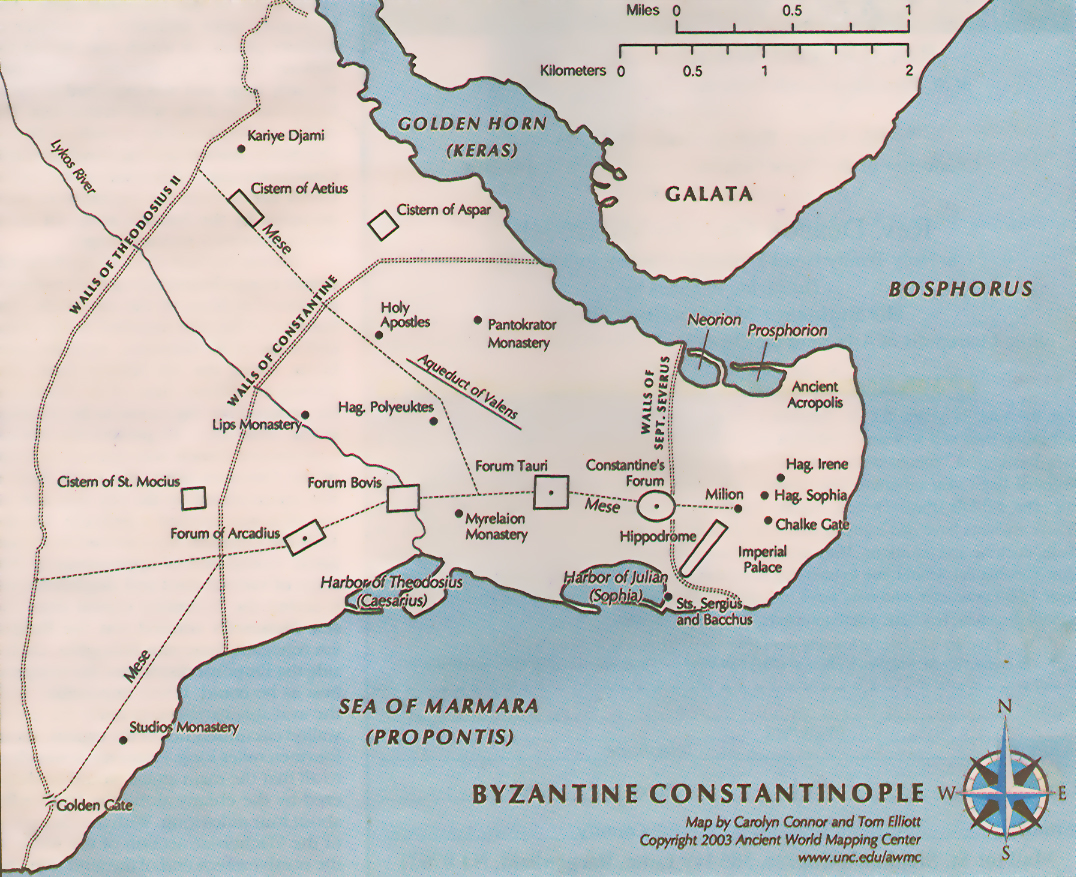

When the siege began the population of the capital amounted, including the refugees from the surrounding area, to about 50,000 people. Behind the enormous walls were inhabited areas separated from each other by fields, orchards, gardens, or even by deserted neighborhoods. Most inhabitants lived near the port area, along the Golden Horn, in view of the Genoese colony of Pera. The city's garrison included 5,000 Greeks and about 2,000 foreigners, mostly Genoese and Venetian. Giustiniani's men were well armed and trained; the rest included small units of well trained soldiers, armed civilians, sailors, volunteers from the foreign communities and also monks. What the defenders lacked in training and armament they possessed in fighting spirit. Indeed, most were killed fighting. A few small caliber artillery pieces, used by the garrison proved ineffective. Despite disagreements over religious policies, and what was seen as capitulation to the Pope, the civilian population supported the Emperor overwhelmingly. The alternative was disastrous. The people, men and women, participated in the repairs of the walls and in the deepening of the foss, volunteers manned |

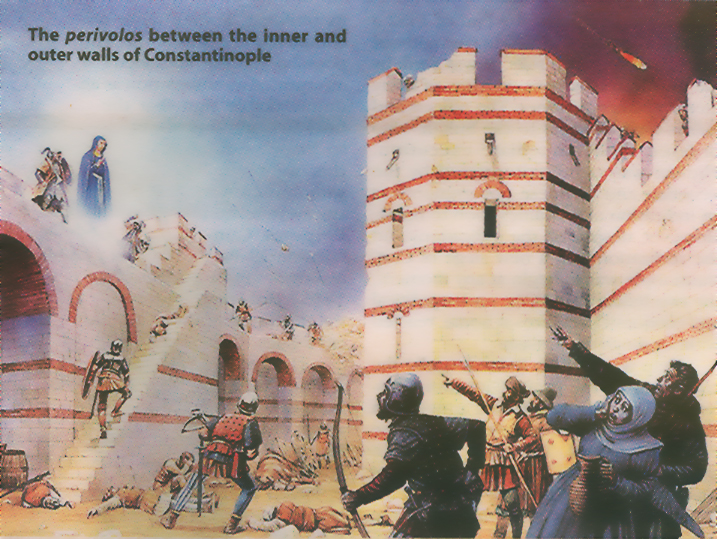

The inner terrace between the inner and outer walls was called the perivolos and accommodated the soldiers who defended the outer wall. It was between 50 and 64 feet wide. Beyond lay the outer wall, which was a modest structure compared with the inner wall. This plate shows a memorable moment during the Ottoman siege An apparition of Virgin Mary on the wall was believed to have heartened the citizens |

|

observation posts, food provisions were collected, gold and silver objects held in the churches were melted to make coins in order to pay the foreign soldiers, the city's harbor, the Golden Horn, was shut by a huge chain. With the exception of about 700 Italian residents of the city who fled on board seven ships, on the night of February 26, no one else imitated them. The rest of the population –Greek and foreign– fought until the bitter end. At the beginning of 1453 the Sultan's army began massing on the plain of Adrianople. Troops came from every region of the Empire. Possibly well over 150,000 men, including thousands of irregulars, from many nationalities, who were attracted by the prospect of looting, were ready to assault the city. The regular troops were well equipped and well trained. The elite corps of the Janissaries composed of abducted Christian children, forcibly converted to Islam, and subsequently trained as professional soldiers, constituted the spear-head of the Ottoman army. The besieging army included a number of artillery pieces, of which one, facing the Military Gate of St. Romanos, was particularly huge and was expected to cause heavy damage to the walls in that area. The army, accompanied by crowds of fanatic Dervishes, started moving slowly towards Constantinople. A few small towns, still in Greek hands, near the capital were soon occupied by the Sultan's army. Of those towns Selymvria resisted longer. During the first week of April the Ottoman troops began taking their assigned positions in front of the city walls. The Sultan had his tent installed north of the civil Gate of St. Romanos, near the river Lycus, facing the 5th Military Gate, also known as Military Gate of St. Romanos. He ordered the big canon to be installed in the same area. To protect the troops, a protective trench was opened in front of the Ottoman units, the earth from it was accumulated on the city side and on top of it was erected a palisade. On the 12th the Ottoman fleet arrived from Gallipoli. Composed of approximately 200 ships of various sizes and displacements, it sealed the Byzantine capital from the sea. Mehmed's admiral was the Bulgarian renegade Suleiman Baltoghlu. On his side the Emperor distributed his troops as best as he could. It was impossible, with the available garrison, to cover the entire walled circumference of the capital, about fourteen miles long. However, it was clear to all that the main attack would be delivered by the enemy along the land-walls, about four miles long. With the exception of the Vlachernae section of the walls, at the north-eastern end of the land side, the city was protected, on the land side, by a triple wall, with a deep foss in front of it. On the sea side, including the Golden Horn port area, the city was protected by a single wall. Given the availability of troops and the critical sections of the walls, Giustiniani, with most of his men, as well as the Emperor and his best troops, took position in the Military St. Romanos Gate sector, where heavy damage was expected to be inflicted by the canon and the main Ottoman assault to be launched. The Venetian Bailo (the Head of the Venetian Community at Constantinople) Girolamo Minotto and his countrymen were charged with the defense of the region of Vlachernae, where the Imperial Palace was located. Minotto and his men faced the European troops of Karadja Pasha. Across the Golden Horn, to the left of Pera, ready to intervene, stood the troops of Zaganos Pasha. Along the southern section of the land-walls the defenders faced the Anatolian troops under the command of Ishak Pasha. The Grand Duke Lukas Notaras, with a reserve unit took position near the walls, at the Petra neighborhood, in the north-eastern section of the city. Another reserve unit was stationed near the church of the Holy Apostles, near the center of the city. Most units were positioned on and behind the land-walls. The sea-walls were thinly manned. To protect the entrance to the port the Venetian commander of the small fleet of the defenders, Alviso Diedo, ordered ten ships to take position behind the chain. Until the end of the siege the Ottoman guns did not stop pounding the walls. Heavy damage was inflicted. The defenders did their best to limit it. They hanged bales of wool, sheets of leather. Nothing could help. The section of the walls in the Lycus valley, near the Emperor's position, was heavily damaged. The foss in front of it was almost filled by the besiegers. Behind it, the defenders erected a stockade, night after night men and women came from the city to repair the damaged sections. – to be continued – Dionysios Hatzopoulos is professor of Classical and Byzantine Studies, and chairman of Hellenic Studies Center at Dawson College, Montreal, and Lecturer at the Department of History at Universite de Montreal, Quebec, Canada. |

|

|

(Posting date 11 July 2006) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|