|

||

|

The Olympic Marathon

|

||

By Alexander Kitroeff* |

From Spyros Louis' victorious win in 1896 to the first women's marathon in 1973, the lengthy journey runs to this day |

|

|

SPYROS Louis' famous win in the marathon at the Athens Olympics of 1896 provided the exclamation mark for those Games. It was the only Greek win in the track and field events and it was in one of the last events. The home crowd greeted Louis' entrance into the Panathenaic Stadium, where he crossed the finishing line, with an outburst of patriotic enthusiasm. It was just as well, then, that the marathon race had been specially invented for the Olympic Games, only a year earlier. It was the brainchild of a Frenchman, Michel Breal, a friend of the reviver of the modern Olympics, the baron de Coubertin. Breal accompanied Coubertin when he travelled to Greece in 1895 to persuade the Greeks to organise the first Olympics. |

||

|

Breal, a romantic phil hellene, stated he would offer a gold cup as a prize if the Greek organisers revived the run from the battleground at Marathon to Athens by the Greek soldier Pheidippides to announce the victory over the Persians in 490BC. According to the legend - no actual evidence exists in any of the sources - Pheidippides ran the roughly 40- kilometre (25-mile) distance at the conclusion of the battle, announced its outcome by gasping out Nenikikamen! and then promptly died of exhaustion. |

||

|

The Greek organisers loved the idea of a race that recalled such a proud moment in Ancient Greek history, and they even had two trial runs. The first trial - the first ever marathon race in history - took place on March 10 (February 27 according to the Julian calendar that was observed in Greece at the time). It involved only Greek runners and the winner was the nineteen-year old Peloponnesian Charilaos Vasilakos, who would come second to Louis in the Olympic marathon, a month later. Legendary Louis Appropriately perhaps for a race based on a legend, Louis, the first winner, became a legend in his own time. He won before a home crowd expecting a Greek win in what was considered a Greek race. The twenty-four year old Louis, a farmer and water carrier who lived in Maroussi just north of Athens (and now one of its suburbs) had taken part in the second trial marathon prior to the Olympics but otherwise he was untrained, and this gave his win its mystique and romanticism and helped him become a legend. The Olympic Stadium that hosts the 2004 Athens Olympics, located very close to Maroussi, is named after Louis. There has probably never been a marathon win again of such tremendous national importance. Coubertin's biographer, Chicago University professor John MacAloon, said that Louis' dramatic victory in the marathon gave the Olympics an aura of heroism that helped them become the major sporting event in the world. The longest race and the most gruelling track and field event, the marathon is now the highlight of each Olympics and traditionally takes place on the last day. Its instant popularity led, within months of the Athens Olympics, to the running of a marathon in Paris and in the American town of Stamford, Connecticut in April 1896 and, most famously, to the establishment of an annual marathon race which began the next year in Boston, Massachusetts, that is now a major event on the international athletic calendar. By being held only every four years, however, the Olympics marathon is the one that attracts the most international attention. From its earliest days it also generated the best myths. A small book can be written about the stories surrounding Louis' origins and the rewards he was promised and actually received for his win. Fanciful stories also emerged about the next marathon winner at the Paris Olympics in 1900. Michel Theato, a resident of France who was born in Luxembourg, was said to have won on a very hot day because he was a baker used to delivering hot croissants to his fellow Parisians. As usually happens, academic research spoiled this good story by ascertaining that Thlato was, in fact a woodworker. Marathon music There have been several dramatic finishes to the Olympic marathons that have involved athletes running neck and neck in the final stretch. The first of these took place at the london Olympics in 1908. This might not have happened if the race's distance had not been extended in order to please the British royal family: they wanted the race to start just outside one of their official residences, Windsor Castle, located just west of london. Although there was no standard distance yet, the previous marathons had been between 25 and 26 miles (or 40 to 41.6 kilometres). In london, the 26-mile maximum distance would have ended the race at the entrance to london's White City stadium. But there would be greater dramatic effect if the runners circled the stadium and ended up in front of the royal box. So another 385 yards were, added. |

||

|

This extra distance proved disastrous for the Italian runner Dorando Pietri who entered the stadium first but then, utterly exhausted, collapsed. Pietri got up, staggered on and fell again but was helped up by officials who eventually had to assist him across the finishing line. This was in clear violation of the rules, and the American team, whose runner John Hays, a New Yorker, came in second to Pietri, lodged a protest. The judges had no option but to disqualify the unlucky Italian and award the gold medal to Hays. In a very British gesture, it was announced that Pietri would receive a special award for the fighting spirit he had shown in adversity. Irving Berlin, one of America's greatest popular composers, had his first big hit with the song' Dorando' , named after the Italian runner. It is about an Italian-American barbershop owner who bets his shop on Dorando winning a race at Madison Square garden. Dorando falls and loses: "Dorando he's a drop! / Goodbye poor old barber shop." And the reason Dorando does not win, according to Berlin, is that the day before he eats Irish beef stew instead of spaghetti. Ironically, Hays was the son of Irish immigrants. |

Kenya's Paul Tergat, one of the favourites to win the 2004 marathon, shows off the gold medal that he won on 28 September 2003 in Berlin with a time of 2:04.55 |

|

|

International race The Korean Kitei Song (Kee ChungSohn) won the marathon at the 1936 Games in Berlin running, unhappily, in Japanese colours because his country was occupied by Japan. This first win by a runner from Asia meant that among the first ten Olympic marathon winners (eleven if we include the Interim Olympics held in Athens in 1906) were runners from all the major continents. After Louis in 1896 and Thlato in 1900, two more runners from Europe won the gold, the Finn Johannes Kolehmainen in 1920 and his compatriot Albin Stenroos in 1924. There were two Americans, Thomas Hicks in 1904 and John Hays in 1908, and a Canadian, Phillip Sherring in 1906. Two winners came from Africa - the South African Kennedy MacArthur in 1912 and the Algerian (running in French colours) Boughera EI Ouafi in 1928. And in 1932, Juan Zabala became the first Olympic marathon winner from Latin America |

||

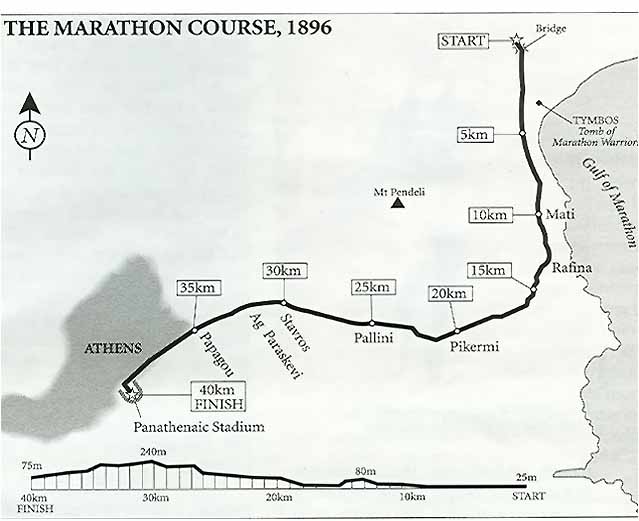

A map of the original 1896 Marathon course. The route is the same for the Athens 2004 Olympics |

||

|

In the aftermath of World War II, the Olympic marathon acquired a new legend: Emil Zatopek..When the Czech runner appeared at the starting line during the 1952 Helsinki Games he caused a great deal of consternation among the other competitors. There was a very good reason why. Zatopek had just won the two major long-distance contests - the 10,000 metres (that he had also won at the London 1948 Games) and the 5,000 metres. He had never, though, competed in a marathon before. In the 10,000m the runner-up was a full 100 metres behind him and in the 5,000m, Zatopek was only in fourth place with half a lap to go, but he sprinted into the lead in the final turn and won easily. In the afternoon, he watched his wife Jana, whom he had met at the London Games, win gold in the javelin throw. Distance runners, especially 10,000metre specialists, often compete in the marathon as well. Delfo Cabrera, the Argentinian winner of the London marathon in 1948, had earlier distinguished himself in the 10,000-metre race in the South American championships. But no one had ever gone on to try for the marathon after winning a long distance race in the same tournament only days earlier. So Zatopek's presence at the starting line caused understandable astonishment, at least to those not familiar with his genuine love of running long distances! As a novice, the Czech runner did not know what the right pace was, so for good measure he ran along with the more experienced favourites who led the race. Then, just past the halfway mark, he found himself ahead of everyone else. There was no mistaking Zatopek' s figure as he entered the stadium, still first. He had the most unorthodox running style, his arms and shoulders flayed about, his head was tilted to one side and his face was contorted in an awful grimace. The lower half of his body seemed to be moving totally independently. The stadium's 70,000 capacity crowd rose to their feet and cheered Zatopek to the finishing line. History had been made, and this extraordinary feat has yet to be repeated. |

||

|

A year before Zatopek' s triumph at Helsinki, a young Ethiopian named Abebe Bikila enlisted in the army because it offered him the opportunity to do the running and physical training he enjoyed. Within a few years it became evident that Bikila was a strong marathon runner, with times very close to those of the Algerianborn Alain Mimoun, who won at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, running in French colours. Bikila was included in the small Ethiopian squad which travelled to Rome for the 1960 Olympics. |

|

|

There was an anti-colonial aura surrounding Mimoun' s win for France at a time when his fellow-Algerians were fighting the French for independence. Something similar was at work when the Ethiopians competed in the capital city of their former colonial masters. Perhaps it was this that energised Bikila on the eve of the marathon, although he had rather more immediate concerns: his running shoes had fallen apart and he could not find a suitable pair to replace them. So he decided he would run barefoot. The marathon was about to acquire a new legend. Bikila not only won, but he also posted a new world record, clocking in at 2 hours, 15 minutes and 16 seconds. It was the first Olympic marathon win under the two-hour-twenty-minute mark.

The only difference between the Rome marathon of 1960 and the one at the next Olympics in Tokyo was that Bikila won wearing shoes this time. He also smashed the record by running eight minutes faster. Thus he became the first athlete to win two consecutive Olympic marathon races. Zatopek may have been the greatest long distance runner to win a marathon, but Bikila was surely the greatest marathon runner of all time. Indeed, Bikila was in with a chance to win a third marathon in Mexico City in 1968, but he injured himself and, not fully fit, had to abandon the race. But Ethiopia did not lose all hope for a third marathon medal in a row because Bikila' s running mate, the 36-year-old Mamo Wolde, was among the leaders. Spurred on by Bikila' s appeal to him to make history, Wolde took the lead around the thirtieth kilometre and kept it until he crossed the finishing line. So Ethiopia became the first and only country to win three consecutive Olympic marathons. But a couple of tragic twists of fate were in store for its champion runners. A few months after the 1968 Olympics Bikila was involved in a car accident in his country that left him paralysed from below the waist. He remained active but fell ill and died five years later. Wolde would suffer as well, as a result of the political instability Ethiopia faced: he spent several years in prison in the 1990s. European dominance After an American Frank Shorter took the gold in the marathon at Munich in 1972, with Wolde coming in third, European runners won the next four. In fact, the East German Waldermar Cierpinski, formerly a steeplechase runner, equalled Bikila's feat by winning the raindrenched marathon at the Montreal Olympics in 1976, with Shorter coming in second, and winning again with a very strong finish at the Moscow 1980 Olympics. Two southern European victories followed at a time when more and more countries were entering athletes for the event. Portugal's Carlos Lopes won in Los Angeles in 1984, at thirty-seven the oldest ever winner, and the Italian Gelindo Bordin won in Seoul in 1988. The Korean Hwang Young-Cho' s victory in Barcelona put an end to this period of European dominance - it was the first win for an Asian runner since his compatriot Kitei Shon (Kee Chung-Sohn) had won in Berlin in 1936. Women' marathon The difficulty women experienced in being treated as equal to men in the Olympic Games is epitomised by how late they had to wait for a women's marathon to be included. It was in Amsterdam in 1928 that women were allowed to compete for the first time in what was considered for them to be a long distance race, the 800 metres. Because many of the competitors collapsed on finishing, the male Olympic administrators decided that women were unsuited to running long distances. Only in the 1970s did attitudes begin to change. In 1973 a women-only marathon was organised in Germany, and was repeated the following year after another one had also been run in California. The first women's marathon at a major international event was held in Athens in 1982 at the European track and field championships and was won by Rosa Mota of Portugal. The first women's Olympic marathon took place in Los Angeles in 1984, with America's Joan Benoit the winner and Grete Waitz of Norway second. Benoit's time was better than that of many male Olympic marathon winners. Another myth about female weakness landed in the dustbin of history as women's marathons proliferated throughout the world. Mota won the bronze medal in Los Angeles but four years later she was the gold medal winner at the Seoul Olympics where only 5 of the 69 starters did not finish. Valentina Yegorova of the former Soviet Union won in Barcelona in 1992 with Japan's Yuko Arimori finishing very close behind her, and 37-year-old Lorraine Moller of New Zealand third. Arimori' s performance was particularly impressive given that she had been born with a congenital dislocation of her foot joint, which was corrected with a cast when she was a child. Ethiopian women followed the example set by their men when Fatuma Roba won at the Atlanta Olympics of 1996 aged twenty-two, with Yegorova and Arimori finishing behind her in the same order as four years earlier. At Sydney it was third time lucky for Japan's quest for women's gold when 28-year-old Naoko Takahashi was the winner. Lidia Simon of Romania was second and Joyce Chepchumba of Kenya third. Takahashi broke Benoit's record, and her success provided a powerful boost for women in Japan, where marathon running is a revered sport. Meanwhile, Japan's Arimori was still in the news, but for the wrong kind of reason. There was media speculation that she was marrying an American in order to move to the United States. Ultimately, she wound up as a Japanese TV commentator at the Sydney Games. Later, she was to make the news for a good reason too. In 1998, she established a non-governmental organisation (NGO) called "Heart of Gold", which aims to offer hope to handicapped people around the world through sports. The NGO also supports self-help activities by war victims in Cambodia and other countries. Africa strikes back The Atlanta 1996 and Sydney 2000 men's marathons witnessed the reemergence of African runners. South African Josiah Thugwane won in Atlanta in an extremely close finish that had Korea's Lee Bong-ju just behind him and the Kenyan Eric Wainaina a close third. The Africans were back and no one was left in any doubt after they captured all three medals in Sydney in 2000. This time Wainana was second, coming in between two Ethiopians, the winner Gezahng Abera and bronze medallist Tesfaye Tola. The three winners shared more than their African identities: high altitude training prior to the Games. "We train high, and compete low," said team doctor Ayalew Tilahun. He was referring to the Ethiopian policy of withdrawing athletes from competition for a month before the Games and putting them through intensive training at the high-altitude team camp in Addis Ababa. And there is one more important ingredient in the Ethiopian and Kenyan preparations, a tactic first adopted by Emil Zatopek. They have intense work outs with a lot of speed training, something that not all long distance coaches and athletes favour. And speaking of great runners such as Zatopek, we must not forget the other ingredient that makes for a champion marathon runner - the sheer will to continue running and to win. "When I felt tired during the race, all I could think was, 'What about all that effort, wasn't it for this?''' explained Abera after he had crossed the finishing line in Sydney. The men's marathon race tomorrow will be all about continuity (as was last Sunday's women's race). The runners will take the same course covered by Spyros Louis back in 1896 and the finish is sure to evoke memories of the revival of the modern Games. But this time there will be no Greek winner. The favourites, according to Sports Illustrated, a leading US sports magazine, are all from Africa Paul Tergat of Kenya, Gert Thys of South Africa and Jaouad Gharib of Morocco. * Alexander Kitroeff was born in Athens. He is professor of history at Haverford College in Pennsylvania and author of Wrestling With the Ancients: Modern Greek Identity and the Olympics, New York, Greekworks.com, 2004 |

||

HCS readers can view other excellent articles by the Athens News writers and staff in many sections of our extensive, permanent archives, especially our News & Issues, Travel in Greece, Business, and Food, Recipes & Garden sections at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||