|

||

|

Onassis in the Dock Again Athens News

By Jonathan Carr

|

||

|

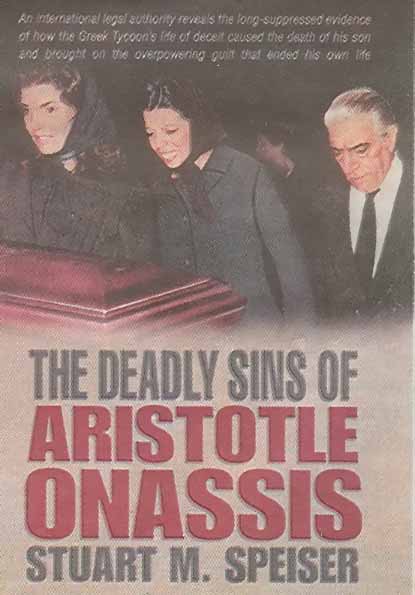

The causes of the plane crash that killed Aristotle's son Alexander, together with the extent of the offlcial cover up, are examined in a new book on the Golden Greek

|

|

|

|

|

The most recent book to come out on the Onassis family |

|

|

One day in November 1977 McCusker got a callout of the blue to say that the manslaughter case reported in the Athens News, hanging over him for nearly five years, had been called for trial that morning and that lie had been acquitted. McCusker, naturally enough, sought compensation arid a few months later he was on the verge of accepting a settlement of $65,000 made by lawyers representing Onassis interests (Aristotle Onassis had died in 1975), when he called Speiser. The upshot was that Speiser, by some legal wizardry he explains in full, set in motion a process that could potentially have brought about an investigation of the Onassis holdings in New York by both the New York State Tax Department and the Internal Revenue Service. Armed with this threat, he negotiated a final settlement of $800,000 for McCusker - a very significant amount in those days. Guilt and responsibility Speiser has not confined himself to writing only about the shenanigans surrounding the McCusker case. At its worst, the book degenerates into outraged moral tub thumping as the innocent 'do the right thing' McCusker is pitted against one of the most evil men of the last century. The opening sentence sets the tone: 'This book presents the story of how the deadly sins of Aristotle Onassis - his arrogance, greed, and lifetime of deceit -led to the death of his son Alexander." With this, the prosecution begins. Speiser makestwo key claims in the book - that Onassis was actually responsible for his son's death and that he died of "guilt rather than grief'. It is no secret that Onassis was devastated by his son's death, but can you distinguish between grief and guilt at such a time, and, frankly, does it ma.tter? It only matters if you have an agenda. And S'peiser does. Onassis' grief is not enough for him. He wants to prove that consummate scoundrels cannot avoid judgement day. So the lawyer, fired up by moral indignation, takes it upon himself to establish guilt. The charges he makes are based on some pretty convoluted arguments. For example, one that keeps cropping up is the role played by the Piaggio and Onassis' obsession with it. He kept the amphibian strapped to his main home, the most luxurious floating residence of its time, the yacht Christina. The Piaggio, Onassis liked to boast, could be used "in all the seas of the world". Speiser, in a digression on amphibians which takes us back to the age of flying boat services, shows that the Piaggio could only be operated safely when wave heights were two feet or less. Most seas, most of the time, have wave heights above this. But Onassis needed to establish what Speiser dubs 'the Myth of the Sea-Going Piaggio' (his capitals) because he wanted the world to believe he was never more than a short flight away from wherever his business empire might need him. In other words, he was always in control. In the Speiser analysis, this fixation with the Piaggio is taken over two more humps to prove Onassis' guilt and personal responsibility for what happened. First, at a dinner with Alexander in Paris less than three weeks before the crash, he apparently agreed (on Alexander's urging) to replace it with a helicopter. But, really, Speiser argues, he was lying as usual. Why this particular lie should have made him feel guilty afterwards, Speiser fails to spell out. Presumably, the implication is that if Onassis had ditched the Piaggio and rustled up a helicopter in those three weeks, the accident would not have happened. Second, the' amphibian's free and faulty service was carried out by Olympic Airways, Onassis' statefinanced personal fiefdom, rather than by established Piaggio mechanics. This is a much stronger point. He further argues that Onassis' s guilt was so deeply felt he deliberately hastened his own death by going against the advice of his eminent New York cardiologist and travelling to Paris for a risky gallbladder operation. Though the operation was successful, he then developed a respiratory infection which would lead to his demise. Speiser puts a different spin on it. "He finally chose death in Paris because the chance of life in New York only meant he would have to go on, day after day,'facing his haunting responsibility for the death of Alexander." Sources It is a pity that Speiser is such a bulldog on the page because he has some good tales to tell and points to make. The first half of the book is a racy account of Onassis' rise from migrant to mogul, beginning with his earliest scams in the tobacco business in Argentina. We learn that it was on a trip between London and Buenos Aires when he met Ingeborg Dedichen, daughter of a prominent Norwegian shipowner. His liaison with her would help smooth the way towards getting finance for his first ship, the modestly-named Ariston, which he used to create what was effectively a new industry - the transport of oil across the world by tanker. To anyone interested in just how crooked and single-minded Onassis was, and how cleverly he built up his business empire, Speiser is a perfectly adequate guide. He provides a lot of detail about his deals, legitimate and otherwise, his lifelong sparring with Stavros Niarchos and his 'trophy' relationships - with Tina Livanos, Maria Callas and Jackie Kennedy. Also, he covers his difficulties with Alexander and Christina. Much of this material, though, comes from secondary sources. Speiser is most convincing over details of the crash itself and its official cover up. His participation in the McCusker case, and his personal interviews with some of those involved, enables him to make public some material that had previously been suppressed. The accident happened when the military junta controlled Greece and critical details about it were covered up by the Colonels, allegedly on Onassis' orders. Conspiracy theorists, encouraged by Onassis himself, blamed the CIA. Speiser shows that it was established from the very beginning that a crucial mistake had been made during the overhaul of the Piaggio when two ailerons - small panels at the edge of each wing were replaced the wrong way round. Effectively, this means that when the pilot expects to turn left, he actually turns right. And when he banks the plane after take-off and it goes the wrong way, it is natural for him to turn it even further the wrong way to try to compensate if he doesn't realise that the controls have been switched. This is exactly what happened and it caused the crash. Are we talking about servicing incompetence or conspiracy? Speiser thinks it was incompetence. Another revelation is the fact that the plane never had its mandatory test flight for the Certificate of Airworthiness it needed from the Civil Aviation Authority even though Olympic had created all the paperwork for it. So the flight that killed Alexander was, in effect, the plane's post-servicing test flight. Cutting corners or conspiracy? Once again, no evidence is put forward suggesting conspiracy. This is interesting material but its credibility and impact is undermined by Speiser's lack of balance and his frequent resort to hyperbolic prose. And why did he wait over 25 years to write this version of events? He does not say. But perhaps he has been short of time. Speiser has no less than 53 books on law and business to his name. The deadly sins of Aristotle Onassis' by Stuart M. Speiser is published by ACW Press. Price approx. 20 euros, hardback, 399 pp ISBN 1-932124-62-4 |

||

HCS readers can view other excellent articles by Jonathan Carr in the News & Issues and especially the sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||