|

Out of the Balkans Book Details Lives of Early 20th Century Greek Immigrants A book review by Mary Papoutsy |

Author: Jason C. Mavrovitis Publisher: Jason C. Mavrovitis, 808 Princeton Drive, Sonoma, CA 95476 Date: 2002 (Revised edition, February 2003) Description: Softbound, 245 pp, illus., maps. Availability: Book may be accessed online at the website of Preservation of American Hellenic Heritage group at: http://www.pahh.com/mavrovitis/index.html Contact author for additional information.

Mavrovitis' acumen as an historical researcher is evident everywhere. The author sought out corroborative data, performed extensive analysis of conflicting information, and determined the reliability of sources. This is the true work of an historian and the process that family researchers should also follow, especially as demonstrated in Appendix A (pp. 239-242), an analysis of conflicting information about one of the family members. But such a tour de force cannot be created, of course, without a firm background in the greater historical context of the events described. Mavrovitis' solid grasp of the complex historical issues is everywhere evident. Fortunate readers benefit from this expertise: the author offers a concise, but factually packed history of the Balkans in the introduction (pp xiv-xviii) that can nicely aid the research of others. Chapter One of Part One, "Eleni and Evangelia: Out of Thrace and the Black Sea," opens with all of the historical drama of a compelling movie plot. A young widow, her husband just trampled by fleeing crowds of Greeks before the rioting Bulgarians, was pulled from the waters with her baby by Greek fisherman. Together with these few survivors of the genocidal pogroms which burned and leveled Greek Sozopolis, they made their way through the Hellespont to the Greek mainland. And so, the story of Jason Mavrovitis begins. Artfully he shifts the scene back to ancient times and takes readers through the significant historical eras, Byzantine and Ottoman, up through the present day. This is an English account of which there are few; readers should take note, especially those tracing ancestry to Greek colonies of the Black Sea.

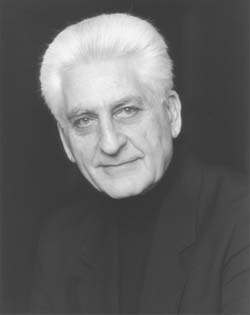

American citizenship was one of the goals for many courageous immigrants, just as it was for Eleni's daughter, Lily, the author's grandmother. Mavrovitis details her repeated attempts to obtain citizenship, information learned only through FOA (Freedom of Information Act) which permits release of government files to selected persons. The importance of this data to the reconstruction of the early years of Eleni and little Lily in the U.S. cannot be overstated. The author himself declares that their life stories "would have been lost" without these records, a clear directive to other researchers to make immigration records a priority in their investigations and to take care to request copies of all extant files on the targeted individuals. From these files, he was able to follow the genealogical thread of references to "court records including depositions and testimony, references to newspaper articles, property deed, addresses in Manhattan, and indications of when other family members came to the United States." In the second chapter Mavrovitis returns to Greece to begin tracing another line of his ancestors from Kastoria in Macedonia. This background sketch offers a wealth of assistance to readers with relatives originating from Kastoria and/or Macedonia. And what's more, they'll all be cheering the daring and bravery of the young andartis skillfully depicted here, as he managed to escape execution by hanging, and a few years later departed for the U.S., beginning a new life that would become the paternal line for Mavrovitis. Subsequent chapters detail the early experiences of his immigrant ancestors in New York, how they found employment, learned and practiced trades, and much more. Mavrovitis vividly portrays the ethnic neighborhoods and activities of early Greek immigrants; pages 65-67, 70-71, and 85-86 may be especially helpful for other researchers or authors of family history. Also be sure to consult another brief section, Appendix B (pp. 242-3), for a nicely crafted description—even if partially fictional, as the author explains--of steerage travel on transatlantic ships; the development of similar passages for family history accounts should be the goal of every genealogical investigation. Several other pages in Mavrovitis' book nicely recount the experiences and career of furriers—pages 82-85—and should be sought out by descendants of Greeks from the Kastoria area and other parts of northern Greece. I reproduce here one short paragraph about the furriers as an example of Mavrovitis' excellent research and descriptions: The factories, behind showrooms and bookkeepers' office space, consisted of large open bays with unfinished wood floors and nine-foot windows. Along the windows wee waist-high benches. Matchers and cutters worked there in the natural light that enabled them to judge fur color and hair height. Close by were rows of machines where operators under the watchful eye and supervision of a matcher and cutter sewed together long pieces of fur skins that had been carefully sliced by the cutter. When joined, these strips reformed the appearance of the fur and, when attached to adjoining skins, attained the shape and style of a designer's conception. Mavrovitis' desire to recreate the everyday lives of Greek immigrants in the U.S. extends beyond the work sector. Readers will find descriptions of home remedies, "country-style" house calls by physicians, and living conditions of these hardy pioneers. I myself particularly enjoyed reading about the mustard plasters and "ventoozes" on p. 99; although these women's remedies are unfamiliar today to many young readers, they were important components of the immigrants' lives because even simple infections at the turn of the twentieth century carried with them fatal risk. Today, in contrast, pneumonia and many viral illnesses no longer claim innocent victims as regularly as they did then. Women's lives were particularly difficult, since many of them worked and cared for their families. Daily household chores were considerably more laborious without our modern conveniences. For instance, kitchens had iceboxes instead of refrigerators, and many apartments were "cold-water" flats. There were no garbage disposals, no dishwashers, or washers and dryers. Baby food was home-made, not bought in stores. Disposable diapers were not yet available, either. Self-sufficiency was one of the most important tenets of the newly-arrived immigrant. Families made or grew as many of their own consumable products as possible. Vegetable gardens supplied fresh produce in season and materials for canning and pickling. Mavrovitis offers a wonderful account of helping his grandfather make homemade wine each year, titled "Grapes, Wine, and Grappa" (pp. 117-119). Among the warmest memories were those surrounding food preparation and comsumption, as one might have predicted. For delicious, home-baked dishes and sumptuous family meals were—and still are--the mainstay of many descendants' memories. Mouth-watering descriptions of family dishes like mussels and rice, and Theo Costa's "lakerda" punctuate the episodes. Mention of traditional "lambropsomo" activates olfactory senses and evokes recollections of "livani" and Holy Week services, while images of the "kadaifi" and "soutzouki" dance like sugar-plums in one's dreams. No readers will remain unaffected by these culinary recollections; this is the time for readers to pick up pens and begin recording their own memories! Mavrovitis closes his family history with a chapter on his army days (WWII), another short one about his trip to Macedonia, and a final one on his return to the U.S. Veterans will enjoy Mr. Mavrovitis' account of his military service in Europe and his return home. Traveling to one's ancestral village is one of the principal goals of Hellenic genealogical research. Many clues abound among the stuccoed houses. Just as Mavrovitis did, researchers should plan to visit all points of interest in the area, including churches, monasteries, offices, and coffeehouses. Many genealogical clues await the patient visitor to one's ancestral village, even if no living relatives remain there. Village elders will know much about local history and may very well remember something about the targeted family or individuals. No genealogical trip should be considered complete without a visit to the local cemetery, especially the village ossuary where remains of relics are held in labeled boxes for decades. In Greece, unlike the U.S., interment lasts only for a few years, at which point the bones of the departed are taken up from the family plot, cleaned, placed lovingly in small wooden boxes labeled with their names and death dates, and stacked in a small structure at the periphery of the cemetery. Mavrovitis' story about visiting his Kastorian relatives—for the first time—will tug at the heart strings of every reader. Anyone who has traveled to Greece and met relatives there will recall the overwhelming feelings such a trip elicits. Tearful hugs and many kisses mark such a life-altering event. The joy of Greek elders at meeting their younger relatives is something that can never be forgotten. And for Mr. Mavrovitis, the trip to Macedonia brought his story around full-circle, hearkening back to the forbears who began their lives and odysseys there in the mountains of northern Greece. This "home-coming" of sorts is an exhortation for every person of Hellenic ancestry to research family history and to travel to the land of his or her ancestors: your heart will resound with the tones of old and beat in the rhythmic patterns of your heritage! Out of the Balkans rates "arista." It's structure, content and indirect didactic function make it invaluable for persons investigating Hellenic ancestry and provide a template for other writers to follow. Does the author achieve his goals? Yes! The narrative account is rich, as accurate as possible, well-written, and preserves the memories of these wonderful relatives. Moreover, the book details in an attractive fashion how the author came to embrace his heritage, a feat meriting an Olympic wreath. Masterfully written, the compelling stories of Mavrovitis' family bring to life the accounts of all of our immigrant ancestors. (Posted February 2004) Jason C. Mavrovitis was born in Brooklyn, New York. He is an alumnus of Columbia University, and of the Executive Program at Stanford University. He also undertook doctoral studies in music, and undergraduate studies in physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Mr. Mavrovitis held executive positions with Stanford University, American Savings, and the University of California, San Francisco, and has been a consultant to universities, city governments, and corporations. Earlier in his career, he was in the aerospace and electronic industries. Since his retirement, Mr. Mavrovitis has devoted his time to the study of Greek, Byzantine, and Balkan history, and classical literature. Mr. Mavrovitis and his wife Bette (née Panayota Gianopoulos - a native of Oakland, California) married in 1960 after they met and courted at the University of California, Berkeley. They live in Sonoma, California. For more information about the author, see his biographical sketch under the Contributing Authors' section of HCS, or visit the author's website at http://www.goldenfleecepublishing.com. Professor Mavrovitis has written a number of fine articles for HCS which readers can browse or read at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/archivemavrovitis.html. 2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |