|

American School Scrapes at Palimpsest of Athens

Since 1931, the American School of Classical Studies has uncovered most of the ancient Agora. The best-funded archaeological school in Athens, it has incorporated the historic Gennadios Library

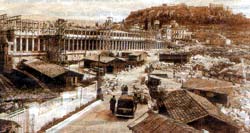

Photos by American School of Classical Studies Looking down at the ancient Athenian Agora, it's hard to imagine this spacious archaeological site as yet another congested district barely 70 years ago. Four hundred buildings were demolished to reclaim the heart of ancient Athens' bustle and turn what was a choice spot of philosophers, jurists, craftsmen and thespians for nearly a millennium into one of the modern city's most striking landmarks. Most of the work on the Agora has been conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), which has excavated extensively here since 1931. Under permission from the Greek state, the school landscaped the area in the early 1950s and rebuilt the Stoa of Attalos (originally a gift to the Athenians by Attalos II of Pergamum in circa 150BC) to house a wealth of finds, ranging from household pottery and statues to weight standards, ostracism ballots and public documents carved in stone. The Adrianou dig Fifty years on, the process to reclaim more sections of the Agora from the modern city continues. On the opposite side of Adrianou St., recently transformed into one of the hottest promenades in town, American archaeologists are excavating a building block believed to contain the remains of several edifices integral to the Agora's history. We know from Pausanias that there were major civic buildings in this area, says ASCSA director Stephen Tracy, an established epigraphist and professor of Classical Studies at Ohio State University. "Places which Socrates and the philosophers were known to frequent, as did the Athenian cavalry." Excavation has already unearthed a Mycenaean grave (the area is believed to have been a burial grounds until about 1200BC) and the remains of two stoas (colonnades) – Stoa Poikila and the Royal Stoa. Tracy notes that the latter was where new office holders took their oath to uphold the city-state's laws. A third key building, the Stoa of the Herms – one of the gathering points of Athenian cavalry prior to horsemanship events practiced during the sacred Panathenaic Festival – still eludes archaeologists. It is believed to lie beneath a corner block currently occupied by a cafeteria, an equipment store and a restaurant (the Epirus). The school is currently negotiating to purchase the land. "It's just a small area, then we're stopping," says Tracy. "All the owners know this area will be expropriated, it's been A zoned for a long time.

Over 30 years ago, it was with some hesitation that the school had to buy out another restaurant – the Ioannina – to make way for the Agora's main entrance. "The Ioannia was one of our favourite restaurants," says Tracy. "These people (on Adrianou St.) have lived with us for a long time, and they know. I had lunch at the Epirus just the other day. Of course, it doesn't mean it will be easy to get them out, and we fully sympathize with them." Real schooling With the number of graduate student and scholars it brings to Greece each year – some 400 in all – the school is probably better for local business than it gets credit for. "We're truly a school," says Tracy. "We have a regular programme from September to June, and a summer session that runs till July." It includes trips to sites, hands-on excavation work and seminars on a variety of topics. "This past year there was a seminar on ancient Greek numismatics, the coming year there will be one on Greek agriculture," says the ASCSA director. "It depends on the expertise of the faculty that are here, and they change every year." There has been no shortage of sites to choose from. Since the school's foundation in 1881, American and Canadian archaeologists have excavated the palace of legendary king Nestor in Pylos, the stadium of the Nemean Games, Minoan shipyears at Kommos, Crete, and a series of theatres at Thoriko, Sikyon, Ikaria and Eretria. But the mainstay of American archaeology in Greece is Ancient Corinth. Begun as an excavation project in 1896, this vast site has since yielded finds from nearly every period of Greek history – from Classical shrines and Roman fast-food eateries, to Byzantine monasteries and 14th century forged Frankish coins.

But for many scholars, one of the school's key functions in Athens has little to do with archaeology at all. The ASCSA administers the Gennadios Library, a treasure trove of books, archives and works on Hellenic heritage since the end of antiquity. Founded by diplomat and scholar Ioannes Gennadios, the library not only houses his own extensive collection on Balkan and Greek history, but also the private papers of German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, Nobel poet laureates George Seferis and Odysseas Elytis, and celebrated Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos. In addition to the thousands of readers it serves each year, the Gennadios has had its share of interesting visitors. During the second world war, its basement was turned into a bomb shelter. The library was later placed under the protection of the Swiss embassy, but this did not prevent a German soldier from making off with parts of Schliemann's archive during the occupation. To prevent further theft, the library was placed under the auspices of the Swedish Red Cross, which proved a more effective safeguard. After the war, a grateful Greek government thanked the Swedes by changing the name of the road in front of the library to Souidias St. Rebuilding a collection The school inherited some 26,000 volumes from Gennadios in 1922, but these did not constitute his entire library. The scholar had already sold off parts of his collection in auctions in 1895, 1898 and 1899, and the school has been trying to race the rare tomes' whereabouts ever since. "About 3,200 of Gennadios' books were sold at Sotheby's, and we have been able either to trace a copy of the same title, or retrieve his own copy for about 170 of those," says associate librarian Anna Nadali. "In many cases, the bookseller himself notifies the library that he has one of Gennadios' copies at hand, and then we raise money to buy it." The library continues to purchase books on historical topics that interested Gennadios, but efforts to reconstruct his original collection is likely to take years. "These books do not easily appear in the market," says Nadali. "Given that they are collectible, their owners keep them. Although it is rather an unrealistic target to gather his whole library again, we keep trying to trace those titles […] We might find one in every five years or so." It wouldn't be the first time the school raises major funds for a project. The ASCSA itself built Samothrace's archaeological museum over a 16-year period (1939-55). Similarly, Nemea's museum was constructed as part of the excavation project by the University of Berkeley, and was handed over to the Greek state in 1984. The gesture is even more remarkable when one considers that these projects were financed independently. Unlike many other foreign schools of archaeology in Athens, the ASCSA is not a state-run institution. "Everyone assumes that we're part of the government, and we're not," says Tracy. "I want to emphasise that we have basically no government funding – we are supported by private gifts, private endowments, and by our 166 cooperating institutions in the United States and Canada." |

|