|

||

|

Paros of Marble and Concrete This central Cycladic island is being over-developed but there is still By Jonathan Carr |

||

|

"LISTEN to me, cuss! " So writes 7th century BC poet Archilochos in one tantalisingly short surviving fragment. A pioneer of iambic verse, this soldier, poet and original thinker had a sharpish wit and tongue. "Hasten on wayfarer," read his epitaph, "lest you stir up the hornets." Born on Paros, Archilochus lived there until he was about forty when he left for Thasos, a Parian colony founded about twenty years earlier by a group led by his father Telesikles. And why did he leave? Allegedly, because he was fed up with it. |

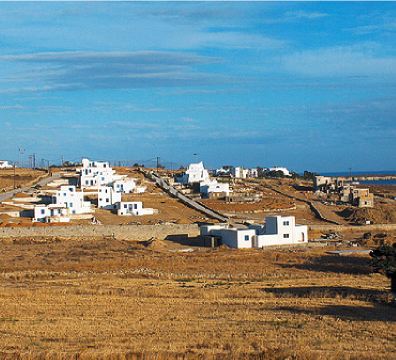

A view of Parikia from the Delion Sanctuary of Apollo |

|

| And I fear he would be fed up and "cussing" now as well. The pace and extent of the island's submission to a thoroughly unoriginal form of tourism is pretty breathtaking. Here are some statistics. Paros has about 11,000 inhabitants - actually close to what it was believed to have had in its glory days of the 5th/4th century BC. There are currently (at the time of my 2006 visit) around 7,000 properties - apartments, houses, plots of land - being touted for sale. About 25 real-estate companies are in business, and those are just the official ones. Probably, never before have so many ΠΩΛΕΙΤΑΙ ('For Sale') signs been posted in such a small place. | ||

|

|

The Mycenaean Acropolis outside Naoussa

|

|

|

Fascinating history |

||

|

The history of Paros is a fascinating feature of the island. There are plenty of ruins to see both in and outside Parikia but a visit to the archaeological museum helps to put things in order and sketch out the plot of the past. Most importantly, it introduces you to Parian marble, early source of both the island's wealth and its artistic development. In the 4th century Paros-born Skopas went on to become one of the most famous sculptors of his time who would work on two of the seven wonders of the ancient world - the temple of Artemis at Ephesus and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Strabo reported that Parian stone was "the best for sculpture in marble". He was probably referring to a kind native to the island known as lychnites, renowned for its brilliance and dug out from deep inside the mountain by slaves under conditions one doesn't want to have to think about. |

The old harbour in Naoussa retains its character |

|

|

Although not huge, there is much to see in the museum. The first person you meet is a gorgon from the first quarter of the 6th century BC. As Photeini Zapheiropoulou explains in the ministry of culture's guidebook, an unknown Parian sculptor humanised the gorgon, giving her a woman's face rather than the traditional visage of a wild beast. What he also did was to create a sense of movement, a feature repeated in a celebrated sculpture of Nike from the second quarter of the 5th century BC, also on show. |

||

|

But the most important exhibit is what is known as the Parian Chronicle, a stele dating back to the 3rd century BC inscribed by an author who evidently had his priorities sorted out, being far more interested in poetry, philosophy and art than politics. Two parts of the stele are in Oxford's Ashmolean museum (another story) but the item on display was discovered in 1897 in Parikia and contains 134 densely-packed lines of information. You won't be able to read it - be grateful somebody has done it for you - but what the Chronicle reports in toto is an impressive 1318 years of Hellenic history, from 1582BC when Kekrops became the first king of Athens to 263BC when Diognetos was the Athenian archon. |

New building developments at Parikia |

|

|

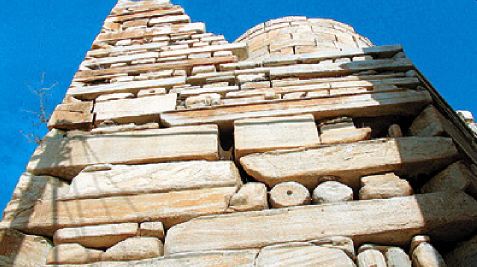

Although the marbled alleys and passageways of the old quarter of Parikia with its mix of balconied villas and traditional houses and public drinking fountains feels as though it must have been designed to disorient, and despite the tale that the trading hub of Market St strikes what is pretty much a straight line through it, everything still seems to lead you via some miracle of geometry to another piece of history that overlooks the sea, the remains of a Frankish Kastro. Partly Frankish, at least. In 1260 Marco Sanudo, the Venetian Duke of Naxos and Cycladic fort builder extraordinaire, took over the site of an old temple to Athena. Indeed, an extraordinary wall survives, in which pillars and masonry from the earlier temple to Athena have been stacked up on top of each other to create an odd mosaic of marble. |

||

| Built in about 525BC the temple to Athena would have been standing when Miltiades, a hero of Marathon (490BC), arrived to punish the Parians, on the face of it because of their support for the Persians though he may just have been after their wealth. In a wonderfully wry account, Herodotus explains how Miltiades, after three weeks of an inconclusive siege, was lured to the temple of Demeter, which neighboured that of Athena and where the church of Constantine and Helena now stands. Instead of getting the advice he was hoping for about how to defeat the Parians, he had a trembling fit, broke his leg and retreated to Athens in shame. He was tried, received a fine rather than the death penalty but the leg went gangrenous and he was dead before he could pay. For this account of ignominy, Herodotus reveals right at the end, "the Parians themselves are my only authority." |

This building detail from Parikia incorporates ancient relics |

|

|

But how did Constantine and Helena slip into that last paragraph? They bring us, via that little sanctuary named after them, to Paros' earliest cathedral, actually three churches in one, which stands in mainly Byzantine shape and colours towards the back of the town. There is a legend that the Empress Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, sheltered on Paros during a storm, had a vision of discovering the True Cross and determined to build a church on the spot. That is at least one of the stories behind the foundation of Panagia Ekatondapyliani ("church of a hundred doors") which is actually believed to have been built under Justinian I in the 6th century AD (about 200 years after Helena's visit). |

||

|

Around the island

Paros is the third largest island in the Cyclades (after Naxos and Andros) but perhaps because of its comparative lack of mountains (the highest is Prophitis Ilias at 770m) and good road network, it does not feel like it. Naoussa, first main stop on the north coast, was once a small fishing port but is now more a fisher of tourists. Even so, there is still character to the old harbour with its unostentatious fish restaurants, its colourful melee of boats and the little whitewashed passageways that lead off from it into the old part of town. Naoussa is also a good place for reaching nearby beaches and, if you are feeling energetic, there is a pleasant climb nearby, up some impressively large smooth rocks to a Mycenaean Acropolis. |

A surviving wall from the Frankish Kastro in Parikia |

|

|

A string of beaches in various states of "development" runs along the east and southern coasts of the island but perhaps the most interesting road cuts across from Piso Livadi, another fishing port that is no longer as small as it was, back towards Parikia. Prodromos is the first village encountered, originally a walled settlement (to provide protection from pirates) and from here a good former Byzantine walking track (there is a road as well) goes up to what was the island's capital through much of the Ottoman period, the village of Lefkes. This is a handsome place in a fine setting with an old square and marbled streets from which traffic is banned. Well worth wandering around, with its large church, its amphitheatre and small Museum of Popular Aegean Civilisation. How to get there |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 29 May 2007 ) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||