|

||

|

Perfidious Albion?

|

||

|

A new book on the ANZAC contribution to the defence of Greece against theNazis casts light on the murky circumstances under which Winston Churchill and his Middle East commander Archibald Wavell secured the alliance ANN ELDER |

Major-General Howard Kippenberger (L) pictured with Captain Charles Upham, awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery in Crete - The Galatas book cover (below) |

|

The two largely Australian and New Zealand divisions posted on Crete, plus one weak armoured brigade and virtually no air support faced 10 German divisions and more than 600 aircraft invading from the north on April 6. As predicted, a massive evacuation was required, ordered on April 22, and carried out by the Royal Navy at night to avoid bombing. |

||

|

The whole Greek operation was botched from the outset by British mishandling, so the Kiwis thought. Winston Churchill placed New Zealander Major-General Bernard Freyberg in charge of the defence of Crete. The more Freyberg saw, the less he liked it, recalls one of his aides-de-camp, retired judge Sir John White, in his unpublished account, The Gamble of Greece. American naval attache in Egypt Henry Stimson, in a dispatch to the US secretary of war, said: "The battle was the fourth disastrous setback to Britain and on account of the divided responsibility, which is part of her command system, she has not yet the faintest conception of where the blame lies." |

The whole Greek operation was botched from the

outset by British mishandling, so the Kiwis thought. Winston Churchill placed New Zealander Major- General Bernard Freyberg in charge of the defense of Crete. The more Freyberg saw, the less he liked it, recalls one of his aide-de-camp, retired judge Sir John White, in his unpublished account, The Gamble of Greece |

|

|

Rank-and-file Kiwis had been no less pessimistic before the fray than the top brass, relates sportswriter-cum-historian Lynn McConnell in Galatas 1941: Courage in Vain. The book usefully focuses purely on fierce fighting round the small village of Galatas, southwest of Hania, during the Battle of Crete, 20-30 May 1941. Launched by publisher Reed NZ in February, it gives a wealth of context, often using unpublished sources and interviews with survivors. The newcomer to military history covers a prickly and often ignored aspect of the business: the relationship between Down Under armies and the British. At the core of the new book, the defiant offensive initiated by Colonel Howard Kippenberger against little Galatas to retake it from Germans on May 25, is told with lively detail. "Uncovering events at Galatas became something of a personal mission," McConnell admits, explaining he took up the project because of material inherited from a relative who had fought on Crete. |

||

A misunderstanding? Australia's and New Zealand's armies were independent, each a national body operating directly under its own governments, answerable to their prime ministers, not the British. In the disastrous Gallipoli invasion in April 1915, Australian and New Zealand forces - which became known then as Anzacs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) - lost thousands of young men. At the outbreak of World War Two, the dominions determined to guard against a repetition of what they saw as fatally inflexible British command methods. The initial aim was to keep the Australian and New Zealand armies as integrated units, separate from the British. To let them be taken over by the British was seen as insulting to the sense of national identity each country by then took pride in. Major decisions, such as deployment of their forces, were to be made by the war cabinets of the two countries. "Yet the situation was irretrievably complex," comments historian FWL Wood in an authoritative account of New Zealand's wartime foreign policy, The NZ People at War: Political and External Affairs (1958). "It remained to be seen what would happen in the heat of battle among men steeped in military tradition." |

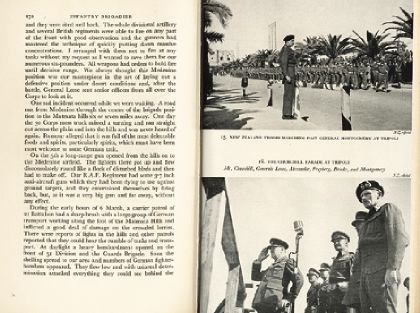

Two photos from Lynn McConnell's book show NZ troops marching past Field Marshal Montgomery at Tripoli, Libya (top) and (above) Churchill saluting at the Tripoli parade, with General Bernard Freyberg in the middle behind him and Montgomery at the right |

|

|

Historian Alan Clark in The Fall of Crete (1962) wrote: "A strange obscurity clouds the outline of the Greek decision [ie the decision to fight in Greece]. In searching for the facts we find that each trail peters out." McConnell relates that no discussion took place about the prospect of New Zealand's involvement in Greece. Wavell informed Freyberg on February 17 that New Zealanders were to be part of Operation Lustre, as the Allied engagement in Greece was codenamed. He assured him approval for the venture had been received from the New Zealand government. But the British request to the New Zealand government that its troops go to Greece was not made till February 25, after Greeks and British had decided on the operation. New Zealand consent to the deployment was given only on March 9. By that time, New Zealand troops were already at sea, travelling to Greece. New Zealand authorities mistakenly thought the move to Greece had been approved by Freyberg because of an unrelated cable he sent saying in general terms that the New Zealand division was "fit for war". Australian agreement was gained in a similar way, when Blamey was told on February 18 his men were also going to Greece. Anthony Beevor (The Battle of Crete) says the Dominion governments later "felt they had not been fully informed". He adds that "both Blamey and Freyberg were to be criticised for not having passed on their private doubts at the time". McConnell offers a different slant. "The decision to go to Greece was taken on a level we could not touch," Freyberg said later. "Wavell told me our government agreed. He had established the right to deal directly with the New Zealand government, without letting me know." Or so Freyberg thought. |

||

Hauled over the coals at a meeting in Cairo in June about the Greek catastrophe by New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser, accused of failing the New Zealand government by not warning that he thought the Greek operation dangerous and unfeasible, Freyberg replied vehemently that as a subordinate officer, he could not under the circumstances challenge his superior. McConnell cites a letter Freyberg wrote to one of his senior officers, Howard Kippenberger, in 1956, reiterating what had happened. Wavell ordered him to tell nobody of the move to Greece, he asserted. When he asked if the New Zealand authorities had been consulted, Wavell said they had been. (He may have thought that was the case from discussions he seems to have had with the Australian prime minister.) |

As days passed in that spring 66 years ago,

it became clear the Allied forces would no sooner arrive in Greece in March than have to be evacuated. To go was 'a strategic blunder', said chief of the imperial general staff, Lord Alanbrooke, retrospectively. The guts of the British attitude was that it was 'better to suffer with the Greeks than to attempt to help them' |

|

|

As days passed in that spring 66 years ago, it became clear the Allied forces would no sooner arrive in Greece in March than have to be evacuated. To go was "a strategic blunder", said the chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lord Alanbrooke, retrospectively. The guts of the British attitude was that it was "better to suffer with the Greeks than to make no attempt to help them".

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill understood the stakes. McConnell sketches Churchill's efforts to secure US logistical support. He believed he had to keep the confidence of the US. Already, President Roosevelt had lent him 50 destroyers. The arrangement was being formalised in the Lend-Lease Bill being debated in Congress late in February. Once news of the move to Greece was conveyed to the US, Congress passed the bill. Americans now understood the British were faithful to agreements to help allies and could be relied on. Greece had scored the first defeat against the Axis powers when it beat back Italian forces through Albania in 1940, providing a morale boost to the isolated British. So British public opinion no less than American would have reacted negatively to Britain turning its back on Greece. Pressure from Churchill no doubt put Wavell in the position of ensuring that Australian and New Zealandtroops were prepared to sail off and defend Greece. Historian Arthur Bryant credited him with "vision and stubborn cunning ... and to have saved the Middle East by a miraculous amalgam of courage, genius and bluff ... in daring, not to say impertinent, strategy. " Wavell agreed: "You were quite right; it was impertinent." (Cited in Bryant's obituary of Wavell, Sunday Times, 28 May 1950.) Later he admitted the expedition "was something in the nature of a gamble with the dice loaded against it from the start". But above him always was Churchill, who "gave his orders in terms of the global situation", as Wood noted. Churchill himself wrote: "The final responsibility lay with us." McConnell shows the pusillanimity of blaming men who failed to do the impossible. As the New Zealand wartime attorney-general HGR Mason commented: "No blame should be passed on to soldiers when the responsibility belonged to politicians." None has been more blamed than Freyberg, a professional soldier in the mould of Achilles, at Churchill's order made commander for the Battle of Crete. Churchill knew his man, had known him since procuring him his first commission in 1914 in the Royal Navy, once counted his 27 battle scars, called him his Salamander (a creature living in fire). He could not have but known what he had asked Freyberg to do, and what it meant to him. The two men met again for the first time after the loss of Crete at Tripoli, on the Mediterranean coast of Libya, on 4 February 1943, at the only full New Zealand division parade in review order throughout the war. Sir John White described the event to McConnell in an interview in December 2004. "Churchill came in and while I was looking straight ahead, I could see out of the corner of my eye. He shook Freyberg's hand and he had tears rolling down his cheeks. He patted Freyberg on the side. Montgomery was with him..." |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 24 May 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||