|

||

|

History is in the detail

|

||

|

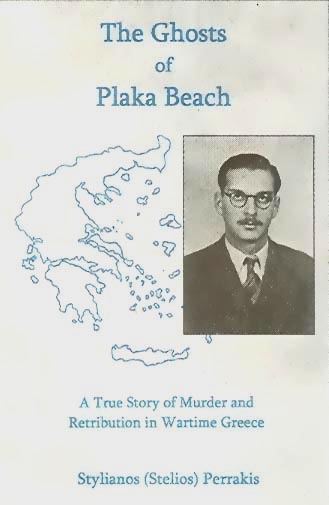

A personal quest to discover the circumstances behind a relative's death sixty years ago drives the narrative of an important new book about wartime Greece |

|

|

| The roughly 40 prisoners were separated into two groups and locked inside a church in the cave. At night, groups of seven or eight were taken outside and murdered. Knives were the weapons used. During the night of May 28/29 Miltis was one of the victims. When Stelios Perrakis, Miltis' nephew, was growing up the circumstances surrounding his uncle's death were never made clear beyond the fact that he had been murdered by Communists who were "the Others, a class of human beings living quietly around us but that formed a constant and permanent threat". By the time Perrakis left Greece in 1964, at the age of 26, he says that this demonisation of the left was already breaking down in his family circle as it became harder, after 12 years of conservative governments, to "swallow the antics" of the right ("our side") and ignore the genuine achievements of the left. Although Perrakis has never come back to live in Greece he has made frequent visits and he always kept in close contact with Miltis' brother Takis (who died in 1994). They frequently argued about why and by whom Miltis was killed. Takis, who remained virulently anti-communist all his life, claimed Miltis' death was the result of a centrally orchestrated campaign of terror by EAM to bring the civilian population of the Argolida under its control. Perrakis saw it differently. Miltis, he believed, had been killed as a class enemy by a leftwing band operating outside the formal control of the Communist Party. Now, in the light of new evidence he has uncovered, Perrakis has changed his mind about the nature of Miltis' death. In The Ghosts of Plaka Beach he casts a wide net over events during the second world war not just in the Argolida but, where it touches on his main story, in Greece as a whole. And it is by looking at the emergence of the different political forces on the right and left at a national level before exploring their influence and activities during the crucial 1943-44 period that he comes to understand what forces were at work in the Argolida at the time Miltis was killed. He discovers that the men who arrested him that morning near Argos were members of OPLA (the Organisation for the Protection of the People's Struggle), a shadowy branch of EAM primarily involved in carrying out abductions and executions of political opponents. Using documentary sources and personal interviews, he concludes that his uncle Takis was right about the nature of the EAM campaign and that, even if he never discovers why Miltis in particular was singled out (various ideas are floated) it was not, as he had thought, a relatively isolated event. "The mass murder at Didyma cannot be divorced from other similar atrocities that were sweeping the Argolida in the summer of 1944. These atrocities, in turn, reflected policy decisions made at higher party levels, certainly as high as the Peloponnese regional KKE [the Greek Communist Party] command, and perhaps as high as the party central committee..." Perrakis argues that what really happened in Greece during the second world war (and in the civil war that followed) has often, for personal and political reasons, either been suppressed or selectively presented or deliberately distorted. Although he is an academic he is not a historian by training and his book, he claims, is a "personal story" that relates to people and events close to him and is "not a history book in any sense of the word". Certainly, it does not conform with a standard history textbook but in its differences lies its strength. Perrakis champions no political grouping, as has so often been the case in accounts of these times, but tries hard to position himself as an honest broker in his quest for how people on all sides behaved in these unnatural times. He does not shirk sensitive issues and he is scrupulous about presenting all the evidence he has uncovered as fully as he can before drawing conclusions. Some of the evidence and conclusions may well surprise. For example, he demonstrates how the widely-held view of the Security Battalions as nothing more than brutal rightwing collaborationist units is not the whole story. Among other factors to be taken into account were the often complex reasons why Greeks joined up in the first place. He is not an apologist - for the Security Battalions or anyone else - but he does show very effectively that in such times of strife and fear, there is rarely a single right answer for anything. Most significantly, he is not afraid to reveal how ordinary people on both sides in the conflict often behaved dishonourably and committed heinous crimes. In particular, he explores the nature and form of retribution that was exercised, always using concrete examples. He encounters compassionate and altruistic deeds too, but not that many. And while he does not condone immoral behaviour, by concentrating on the minutiae of many individual lives (not just those of the Melissinos family) and by flagging the extraordinary pressures named individuals were living under, the genuine injustices they faced and the tough choices they were often being forced to make, he evinces a real world of flawed human beings. There are some outright villains and no real heroes. Mostly, humans stumble about somewhere in the middle. In his own words: "Those two archetypes, the Hero and the Villain, coexist in reality very often within the same person, and both are given a chance to surface in the troubled times of war and revolution much more often than our history books care to admit." The thoroughness of his research sometimes leads Perrakis to include more information and detail than necessary to make a point and there are instances of repetition but these are small defects in a book that is an important record of these times. The issues he raises, the questions he poses and the evidence he tables go beyond their Greek context and are relevant to the study of any conflict situation. How, for example, should justice for wartime crimes such as the murder of Miltis Melissinos be exercised? Who should be held responsible? The man who drew the knife and/or the man who gave the order? This is the kind of issue given solid historical context by the intricate detail of The Ghosts of Plaka Beach. * 'The Ghosts of Plaka Beach: A True Story of Murder and Retribution in Wartime Greece' by Stylianos (Stelios) Perrakis (ISBN 0-8386-4090-7) is published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press and is available at central Athens bookstores or via www.amazon.co.uk |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 5 September 2006) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||