|

|

|

Rare Greek Antiquities Go on Display in New York |

|

NEW YORK — Warned that the barrage of Persian arrows would hide the sun at Thermopylae, the Spartan hero Dienekes replied with cool bravado, "It will be pleasant to fight in the shade." Known for their terse, unflinching way of speaking, these consummate warriors from the Lakonia region of Greece were known as laconic, or sparing of words. The term also applies to their art. |

|

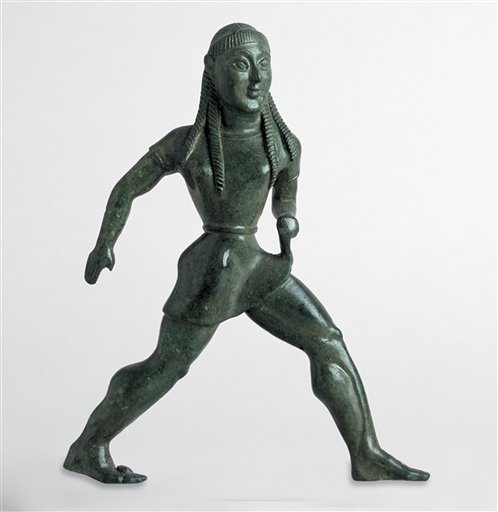

| Athens lavishly encouraged artistic creativity, which became the fountainhead of Western civilization. Laconic, militarist Sparta spent sparingly on the arts, yet managed to produce its own notable works, as shown by the celebrated objects on display. Mounted strikingly in the compact gallery in midtown, the survey encompasses some of the rarest relics ever to travel outside Greece, dating from 800 B.C. to about 350 B.C. Admission is free for the one-time show, on view through May 12, 2007. Artifacts from centuries of conflicts include spear points and javelin tips from the 480 B.C. battlefield of Thermopylae, where 300 Spartans fought to the last man against Xerxes' overwhelming forces; a large marble bust commemorating Leonidas, the Spartan king who died with his troops at Thermopylae; a marble relief of an Athenian trireme warship in action; and a bronze Assyrian helmet from the 490 B.C. Battle of Marathon, Athens' war booty offering at the shrine to Zeus at Olympia. Objects from the domestic and religious life of both cities include intricately painted pottery and drinking vessels, metallic sculptures of athletes and votive figurines, coins and decorative pins. Other artifacts include gravestones carved from marble and busts and statues of Athena, the patron of Athens, and other Panhellenic gods. Greece's greatest museums in Athens, Sparta, Marathon, Olympia and Rhodes loaned priceless objects for the show. A lavishly illustrated catalog includes essays by Greece's top antiquities scholars. Among them are Nikolaos Kaltsas, director of the National Archaeological Museums, who curated the show. Wallboards and labels on the artifacts trace a history of shifting alliances and hostilities rooted in radically different social organizations and cultural ideals in Athens and Sparta. Sparta, militant and highly regimented, bred the best soldiers of the Hellenic world by making its residents subservient to the state. Humanist Athens produced the greatest philosophers and builders by encouraging freethinking among its citizens. Sparta thrived as an oligarchy, Athens as a democracy. Slavery was part of both societies. Athens' artists and its sea-borne commerce dominated the Mediterranean region, generating wealth and underwriting intellectual achievements such as the Parthenon and theatrical tragedy. Spartan traders and craftsmen also brought prosperity to their society, although military preparedness was always uppermost and artistic creativity a lesser concern. Mutually antagonistic for centuries, the two powers and their allies set aside enmities and formed a common front when Persian invaders on land and sea threatened to overrun Greece in the early fifth century. In 490 B.C., 10,000 Athenian troops turned the tide at Marathon, routing twice as many Persians. When a larger force of Persians invaded again in 480 B.C., the Spartans galvanized Panhellenic resistance with their heroic, three-day stand at Thermopylae. The Athenian naval victory at Salamis later in the year, and the Spartan-led battlefield triumph at Plataeae in 479 B.C. all but ended serious Persian designs on the Greek mainland. But Hellenic animosities rooted in clashing ideals eventually led to the Peloponnesian War, 431 B.C. to 404 B.C., which ended in Sparta's defeat of Athens. One of the clearest examples of their stark difference in world views is reflected in steles, or gravestones. The Spartan leader Lycurgus banned inscriptions of names on graves, except for "those who died in war" and women who died in childbirth. In contrast, Athenian gravestones commissioned by the wealthy were artistically carved reliefs depicting the deceased, often based on works at the Parthenon or other great monuments. The expenses led to legislative efforts against such extravagant memorials, the exhibition notes. |

|

|

(Posting date 24 January 2007) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|