|

|

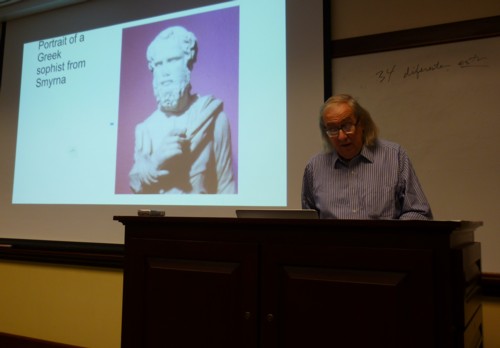

Professor Ewen Bowie of Oxford University Speaks at University of New Hampshire

|

On a recent tour of the United States, this world-renowned Classicist delivered a lecture at Durham for students and faculty interested in Classical antiquity. The Janetos Fund at UNH sponsored the scholar's visit. The title of his talk was "Rewards for Superstars in the Roman Empire," a superbly engaging discourse on the amounts and types of rewards given to rhetoricians. Dr. Bowie brought forward extant evidence for the rewards, comparing the gains of rhetores to the salaries of civil servants and military leaders, as well as to the gains of musicians, poets, and actors.

Overall, rhetoricians didn't gain as much athletes and civil servants, suggesting that the honors afforded the rhetores were their greatest rewards. Themistocles of Ilion, touring cities of Asia Minor and delivering speeches, not only received 400 drachmae, but the Xanthians of Lycia also inscribed a public decree on a stela at the shrine of Leto for him, sending a second copy to Ilion.

|

Dr. Ewen Bowie of Oxford University lectures at UNH.

Photo by Mary Papoutsy.

|

Others secured elevated status or Roman citizenship for themselves and their families or special privileges for their hometowns. Sometimes great performances led to appointments as tutors or civil servants. For outstanding individuals with imperial favor, very large sums of money, sometimes running into the equivalent of millions of dollars, were possible.

Among the intersting monetary statistics offered by Bowie were

- Herodes Atticus gave Scopelianus a gift of 90,000 drachmae (worth nearly $1,000,000) when he visited Atticus' house around 116 A.D.

- Herodes' Atticus' gave a fee of 250,000 drachmas to Polemo, after Polemo refused a fee of 150,000. This amount is the rough equivalent of $2,500,000 today.

- Alexander of Seleuceia received gifts of 20 talents of gold plus other gifts. 20 talents equals about $1,250,000.

- Marcus Aurelius gave gifts and rewards to Hadrianus of Tyre in 176 A.D.: gold, silver, horses, slaves, the right to live in Rome, free food and lodging in Rome, and other privileges.

|

Equally interesting were comparisons of the rewards of rhetores to the salaries of civil servants, military officers, and to the prizes of athletes, actors, and musicians. Most good rhetores could expect to earn sums similar to lower-ranking equestrian officers and civil servants--5,000-10,000 drachmae. But the academics started out at a lower monetary scale and only attained these amounts after a robust career. Equestrians could advance to better positions with greater compensation. In comparison, musicians, poets, and actors at festival competitions generally earned far less prize-money at each performance, according to extant records. Athletic competitons earned winners more drachmas overall, but scholars believe that the length of their careers would have been shorter.

An engaging speaker, this soft-spoken scholar captivated his university audience with the breadth and depth of his knowledge of the ancient world. Following his appearance at Durham, Dr. Bowie was scheduled to visit Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine.

Further Reading (selected from among the hand-out provided by Dr. Bowie)

- Boatwright, M.T. 2000. Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bowersock, G. W. 1969. Greek Sophists in the Roman Empire. Oxford:Oxford University Press

- Bowie, E.L. 1982. "The Importance of Sophists," Yale Classical Studies 27:29-50.

- Bowie, E.. 1997. "Plutarch, Hadrian and Favorinus," in J.M. Mossman (ed.), Plutarch and His Intellectual World. Cardiff: 1-18.

- Bowie, E.L. 2004, "The geography of the second sophistic: cultural variations," in B. E. Borg (ed.) Paideia: the World of the Second Sophistic. Berlin-NY:65-83.

- Devijver, H. 1989. The Equestrian Officers of the Roman Army. Amsterdam: Gieben.

- Dobson, B. 1972. "Legionary Centurion or Equestrian Officer? A Comparison of Pay and Prospects," Ancient Society 3: 193-207.

- Koenig, J. 2005. Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press.

- Ma, J. 2000. Antiochus III and the Cities of Western Asia Minor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nisbet, G. 2004. Martial's Forgotten Rivals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Power, T. 2010. The Culture of Kitharoidia. Washington, DC: The Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Reynolds, J. 1982. Aphrodisias and Rome. Britannia Monograph Series. London: Roman Society Publications.

- Roueche, C. 1993. Performers and Partisans at Aphrodisias in the Roman and Late Roman Periods. Journal of Roman Studies Monograph. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

- Russell, D.A. (1990) (ed.) Antonine Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Stephanes, I. E. 1988. Dionysiakoi technitai: symvoles sten prosopographia tou theatrou kai tes mousikes ton archaion Hellenon. Heraklion.

- van Nijf, O. 1999. "Athletics, Festivals and Greek Identity in the Roman East," Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 45: 176-199.

- Whitmarsh, T. 2004. "The Cretan Lyre Paradox: Mesomedes, Hadrian and the Poetics of Patronage" in B. B. Borg (ed.), Paideia: the World of the Second Sophistic. Berlin-NY: 377-402.

- Newby, Z. 2005. Greek Athletics in the Roman World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

|

(Posting date 24 September 2013)

HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html.

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com

|