|

||

|

The End of the Macedonian Struggle |

||

|

EFTHYMIOS TSILIOPOULOS JULY 11 1908 is considered by most to be the end of the Macedonian Struggle. Sultan Abdul Hamid had acquiesced to the demands of the Young Turks, promising to establish a constitution and hold elections, and declaring an amnesty for all parties involved in the fighting that had raged in Macedonia since 1904. |

|

|

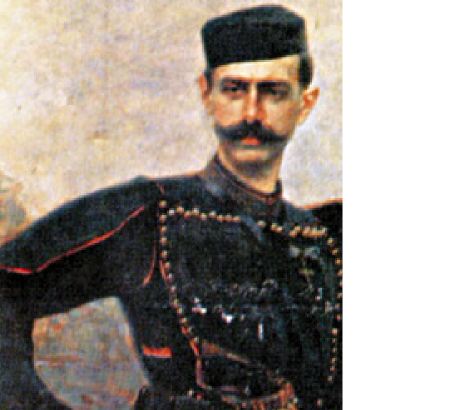

| Patriarchate in Constantinople), especially in the foundation of schools. A clandestine organisation was set up within Ottoman territory, the IMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation), to spread Bulgarian influence. In 1899, the IMRO turned against the Ottoman authorities under the slogan "autonomy for Macedonia". Since they purported to be protectors of all Christians, Greek reactions were at first lukewarm. However, the pressure applied to locals to come out in favour of the Exarhate and against the patriarch exacerbated tensions, augmenting ethnic tendencies, which up until that point were rather hazy in this multilingual region. Quickly, the milder tactics of propaganda, payoffs and extortion were supplemented by beatings, arson, rustling and assassination. Chief targets were the (mostly Greek) pro-Patriarchate notables, teachers and clergy. Despite the rise of atrocities, Greece was still reeling from its defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1897). The nationalist organisation that had paved the way to war, the Ethniki Etairia, was officially disbanded by the Greek government. However, the young officers that were its backbone were very alarmed at the situation north of the border. In April 1903, a Bulgarian group known as the Gemidzhii Circle blew up infrastructure, cafes, the French ship Guadalquivir and the Ottoman Bank in Thessaloniki, setting off large-scale Ottoman reprisals. Despite the setback, that August the IMRO felt confident enough to organise the Ilinden Uprising. The Ottomans crushed the uprising, levelling many villages in western Macedonia and around Kirk-Klisse, near Adrianople. Despite this setback, the Bulgarians stepped up activities and began to terrorise Greeks especially in the areas of Florina and Kastoria. It was the bishop of Kastoria, Germanos Karavangelis, and the Greek consul in Bitola, Ion Dragoumis, that began organising the Greek opposition, even though official Greek aid was not initially forthcoming. Taking advantage of rifts within the IMRO and using his fiery rhetoric and an open purse, Karavangelis succeeded in recruiting disgruntled former members, some of whom came to regard themselves as Slavophone Greeks who had lost track of their ethnic roots, while others fully identified with Greek identity. Eventually, these Greek guerrilla bands, the Makedonomahoi (Macedonian Fighters), were strengthened with Greek Army officers and volunteers from Greeece proper. Perhaps the best-known of these army officers was Pavlos Melas (photo). With a small unit of men, he fought against the Bulgarians until he was killed by Ottoman gendarmes in the village of Statitsa, in October 1904. Becoming a far more important in death, his strong political connections pressurised the Athens government into reinforcing the struggle. Fighting became widespread and vicious, with both sides committing atrocities. The areas around Yiannitsa, Kastoria and Florina became the main battlefields, resulting in the gradual destitution of the local populations. By the time of the Young Turk revolt, in 1908, the inhabitants of Macedonia on all sides had had enough. The conflict did not really end there. It simply became almost dormant. It soon became apparent that the Turks had no intention of honouring their pledges. By 1912, it was clear that the Balkan countries had to deal with the matter militarily, first against Turkey and then among themselves. The seeds of the Balkan Wars, and the First World War, had been sown. |

||

|

(Posting Date 4 August 2008 ) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||