|

||

|

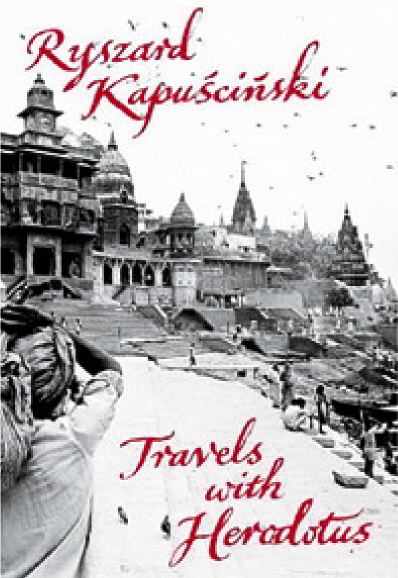

Two Masters of Allusion: A Review of Travels with Herodotus

|

||

| By Jonathan Carr

In his final book, long-serving Polish foreign correspondent Ryszard Kapuscinski reveals his debt to Herodotus How fitting it is that the last major work to be published by Ryszard Kapuscinski, the Polish-born aficionado of trouble spots (he reported on 27 coups and revolutions around the world) should be an account of his gratitude to the man he revered as his teacher and guide, the "wise, experienced Greek" - Herodotus. In Travels with Herodotus we are treated not just to a beguiling weave of the political and military machinations of ancient Greece and the second half of the 20th century that is in itself unique but also to an intelligent inquiry into what Kapuscinski has elsewhere dubbed the "mystery of history". The book is an affirmation, at times a defence, of his lifelong journalistic principles, though its author would never dream of making that point so bluntly. Early on, we are reminded that he grew up in a totalitarian state where there was an "obsession with allusion" and he is quick to state that his idol from Halicarnassus was a master of the art. Reader beware! |

||

|

Kapuscinski, who died on January 23 aged 75, was regarded by many as one of the greatest foreign correspondents of his generation - and rightly so. He reported from all over Asia (India, China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran), from Russia and from Latin America, but it was his long stint in Africa that marked him most profoundly as a writer. His formative years were spent there and that is when, with Herodotus' assistance, he honed his craft. Nobody reported on the chaotic breakup of that continent's colonies with Kapuscinski's degree of empathy and insight (he too was a citizen of a country that was imperial prey). And nobody was there - everywhere - as he was. |

|

|

| His reportage takes two forms, the one feeding into the other. First, there is the relatively straightforward business of covering events in the field and filing stories for his employer, the Polish Press Agency. It is only relatively straightforward because, as Kapuscinski likes to remind us, he is often denied the funds and equipment available to his colleagues at Reuters, AP or AFP. He therefore has to be more resourceful. His disappearances into the middle of nowhere with nothing but the shirt on his back in search of a story are legendary. In Travels with Herodotus he writes: "¨So I walk, ask, listen, cajole, scrape and string together...[and here come a significant trio of nouns]...facts, opinions, stories." Kapuscinski's detractors have accused him of habitually making things up and this charge is generally levelled at his second form of journalistic output. This reportage is the work he writes later. Though still based on events he has witnessed, he can be more discursive, he is free from journalistic rules and word counts and he has the luxury of reflection. With his innate curiosity and wisdom, his eye for the all-important detail, his lyrical flourishes (the roofs of Peking, with their tips curled upward "resembled a gigantic flock of motionless black birds awaiting the signal to take flight") and the skilful way in which he manages his material, deftly withholding information to heighten its dramatic impact, Kapuscinski can transform what might in other hands have been merely an interesting record of turbulent times into a work of literature. The Emperor, concurrently an account of the last days of Haile Selassie in Ethiopia and a meditation on the evil of absolute power (and how might that have been interpreted in his native Poland?) was the first of his books to be translated into English. Five more followed, including Another Day of Life, where he was witness to the disorderly exit of the Portuguese from Angola; Shah of Shahs, where he was covering the revolution in Iran; and Imperium, in which he interpreted the collapse of his own local behemoth, the Soviet Union. The latitude he might sometimes take in these books - blurring time by not including dates or confusing the strict order of events - is what offends those detractors of his. But, as he once put it in an interview in Granta magazine, he wants to express "what surrounds the story. The climate, the atmosphere of the street, the feeling of the people, the gossip of the town, the smell; the thousand, thousand elements of reality that are part of the event you read about in 600 words in your morning paper." That is exactly what he did so well. In this final book of his we learn how much he picked up from studying his mentor's techniques. Travels with Herodotus unfolds with characteristic ingenuity. Two narratives gently accelerate alongside each other. Selected episodes from Kapuscinski's life as a reporter in loose chronological order are interspersed with insightful commentaries on his favourite scenes (that include lengthy quotations) from Herodotus' account of the events leading up to and including the Persian wars. There are plenty of diversions, most engagingly when he puzzles over one of the Greek's apparently throwaway remarks. On one occasion, for example, Cyrus is leading his army from his capital at Susa to the faraway shores of Amu Darya. It is a mad enterprise that Kapuscinski compares to Napoleon's campaign to reach Moscow, one that is bound to fail and lead to great loss of life. The detail that intrigues him is how Cyrus' thirst is quenched. The great king will only drink water from the River Choaspes that has been pre-boiled. It is transported in silver containers in four-wheeled wagons across the desert. "What connection between the water wagons," he asks, "and the soldiers dropping of thirst along the way?" There is none, he concludes, because the soldiers do not matter compared to the king. And what about Croesus, the other (captive) monarch travelling with Cyrus? What and how did he drink? With Cyrus, perhaps? Or from his own barrel? Kapuscinski, fascination aside, is making a point. How magnificently, he is saying, Herodotus builds up his characters for a fall. Both Cyrus and Croesus continue to violate, and flagrantly so, one of the cardinal rules of Herodotus' world - that although no human may be able to avoid his destiny he should always approach it with humility. Kapuscinski's greatest feat is to create an enthralling double-drama that spans 2,500 years. While stranded in the middle of a collapsing Congo, he experiences what he labels the only "true loneliness" he has ever known. He feels it when faced by "absolute violent power", represented in this case by two heavily-armed policemen who are, with apparently menacing intent, walking towards him. Even so, he confesses that he is so full of "dread" about the approaching war between the Greeks and Persians that it sometimes seems more real for him than the Congolese conflict he is covering. A touch of hyperbole? Or perhaps a survival method? It does not matter. The reader is - vividly - in two places at the same time. Most journalism is quickly forgotten. Kapuscinski has, with Herodotus' help, ensured that his will endure. And although he is careful in Travels with Herodotus to maintain an entirely respectable distance from the Greek "giant", there are, of course, plenty of allusions that can be drawn between the two of them. 'Travels with Herodotus' by Ryszard Kapuscinski (translated by Klara Glowczewska) is published by Allen Lane and is available in central Athens bookstores or via www.amazon.co.uk. [For U.S. availability, see HCS book announcement for Travels with Herodotus.] |

||

|

|

||

(Posting 15 November 2007 ) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||