|

Greek Independence Day

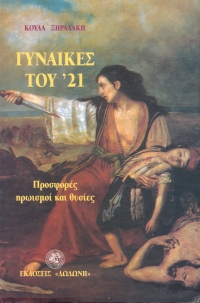

“The women, entrapped, turned towards the steep cliff. It was December 16, 1803 when the dance began. As the enemy charged against them, the women—one by one—threw their children from the cliff before jumping after them themselves. The decision: to choose death over enslavement.”

It was just prior to 1600 when Souli was first settled by that one family. One hundred years later, the families who lived in the four village (“Tetrahori”) of the area numbered one thousand. Little by little, the fame of Souli spread throughout Epirus: new “colonists” continued to arrive, knowing that however more difficult life would be, there was one clear advantage—the people of Souli lived autonomously, free from the abuses of the “agas.”

For the head of the Ottoman Empire, the matter began to be worrisome when reports cam in from Yiannina informing them that not only did the Souliotes not pay taxes to the empire (that was a given), but they demanded tribute from the Turks of the area. And they provided protection for 66 Christian villages whose residents extended hospitality to them in hard times. The autonomous community began to spread as a country within a county. The order for the pasha of Yiannina to “finish the Souliotes” came in 1732. Although Hadji Pasha began an expedition to the remote area, with 3,000 men, he chose to return to the safety of his palace once the first salvo was fired. Another twenty years passed before anyone ever thought of bothering the Souliotes again. It was 1752, when Mustapha Pasha of Yiannina was given the order to destroy Souli. This time there was a battle. The defeat of the Turks was decisive. For another four decades, the autonomous state was ignored by the Ottoman Empire—until Ali Pasha came into power. The army of Ali Pasha made its first appearance in 1792 and was soundly defeated. Eight years later the satrap of Yiannina was defeated again and left. In 1802, he led 18,000 men in an effort to take Souli by surprise. But a surprise with such a large force was impossible. The Souliotes waited for them to enter the area and crushed them. Finally, Ali Pasha though of a new tactic: for a castle to fall, even one made by nature a such was Souli, it needed to be besieged and then taken from the inside. In the beginning the Souliotes were not troubled by the siege. But month after month the siege tightened fields were lost, and men and animals suffered from lack of food. The iinternational community became concerned with the matter and in April 1803, the French unloaded food supplies and munitions for the besieged in Parga. But Ali took advantage of the occasion, convincing the agas of the area that they were facing an international conspiracy that would develop into a threat against them all. It was no longer a personal matter between the pasha and the Souliotes. Thousands of Turks and Albanians reinforced him. He began building towers at the exits of the area, attempting to construct a giant trap. The following autumn, the giant trap was completed, but Souli would not fall. He needed the help of someone from the inside. Many patriots and heroic fighters had come out of the Gousis family. But the family also produced Pelios Gousis, who imagined life rather differently. Ali’s men located Pelios and Ali’s second son, Veli Pasha, was sent to meet and strike a sescret deal with him. On the specified night, the Turkish-Albanians attacked,l firing on the Souliotes from behind, where Pelios and his men were supposed to be. In the darkness and the upheaval, the Souliotes were forced to retreat within the fortified enclosure of the church of Aghia Paraskevi, in Kougi. By day, Veli’s forces were inside Souli, with the besieged in Aghia Paraskevi continuing to fight. Of the 400 who were fighting in Kougi, some broke through the encirclements with scimitars in hand and were saved. But most, led by Samuel the monk, put fire to the munitions and blew themselves up, along with a good number of Ali’s men. For the rest, the only way was an honorable peace. The treaty of surrender was signed on December 12, 1803, which allowed the Souliotes to take their weapons and go wherever they pleased. On December 15, men, women and children were divided into three groups headed to either Zalongo, Vouganeri or Parga. They had not started out when Ali gave the order to hit them. The group heading towards Parga managed to escape. The group headed to Voulganeri ended up wandering until spring. But the enemy caught the first group at Zalongo, where the Souliotes defended themselves. It was an uneven battle. Forced to retreat, some of the men survived. The women, entrapped, turned towards the steep cliff. It was December 16, 1803, when the dance began. As the enemy charged against them, the women—one by one—threw their children from the cliff before jumping after them themselves. The decision: to choose death over enslavement.

|

|||||||

Back to Greek Independence Day Commemorative Series

|