|

Business Ethics Overview Earnings and Ethics Investing: What is Moral? By Christos Papoutsy |

During this time of corruption and public scandals in business, government, religion and journalism, a greater percentage of the investing public is searching for places to put their money that consider ethics as part of their mission and strategy. Over $13 billion is invested in U.S. public mutual funds that focus on socially responsible investing. That amounts to about one-half of one percent of the total mutual-fund assets. "More than 700 independent asset managers [of socially responsible mutual funds] identify themselves as portfolio managers for institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals," according to a recent article in Across the Board, the magazine of the Conference Board. The size of most of these funds, however, remains small: 18 have more than $100 million in assets; 4 report more than $1 billion. What are the returns on socially responsible investing versus returns on other types of stock investments? The Domini Social 400-Stock Index, which tracks the performance of companies that pass a series of moral screens, returned an annual average of 9.64 percent for the 10 years ending April 30th 2003. The return of the benchmark Standard and Poor's 500-Stock Index over the same period was almost precisely the same: 9.66 percent. Based on these two statistics, it would appear that you can have your ethical cake and eat it, too. Yet there are no offsetting credits awarded for the production of life-saving cat-scan equipment for hospitals. And this is the crux of the problem with socially responsible investing: the criteria are all based upon personal values and appear to be applied selectively. There is no standard set of screening criteria for so-called socially responsible funds. Under these conditions, how can a mutual fund or financial advisor tell the investor what is socially responsible and what's not? In this era of globalization screening and rating, to determine which companies are socially responsible is difficult. Corporations now purchase parts and components for their products from hundreds of vendors throughout the world, vendors who often sub-contract significant segments to other vendors, and so on. So-called socially responsible corporations often sell their products, publicized as ethically pure, to other corporations around the world that in turn re-sell or incorporate these elements into products that would never meet the current standards of socially responsible screening. Moreover, who would set the guidelines for the screening and rating of each company's most valuable asset, its employees? If we are to be socially responsible, should we not also apply the same standards to this precious asset? Companies that employ persons who smoke, drink, gamble, drive SUVs, and pollute the environment, for example, ought to be eliminated from investment consideration. And what about the vendors, customers, stockholders and all other stakeholders for these subject companies? Whose values, standards and ethics are to be applied in screening and rating not only public and private corporations, but also an entire society that makes up the corporate policy? A corporation is a living, dynamic entity, a mosaic of many different people, with diverse ethnic, religious, and educational backgrounds, all of whom operate in the new global economy. A different approach -- for those persons interested in social responsibility -- may be required for this worldwide market. One method might be for individual investors to donate their profits, earned ethically and legally through regular investing and hard work, to charitable groups. With this proposed method, the distribution of one's investment profit receives the emphasis, not the screening process of current socially responsible mutual funds. This approach might serve as a practical alternative to the current

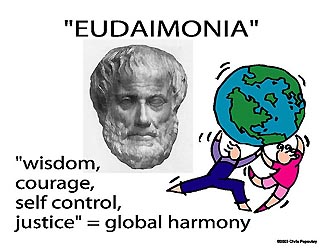

The global investing community is seeking value. In the new global economy, asset managers and financial planners will be seeking to discover the underlying code of real value creation. New methods will be developed, I predict, to decode the economic DNA of businesses, revealing the essential building blocks of commercial worth: unique value-creating characteristics of all the assets of a corporation, both tangible and intangible. The global corporation will need to develop a universal system of business values with a common denominator of ethics practiced by all stakeholders. This, in turn, will create a framework of Aristotelian harmony and global eudaimonia, the material and spiritual well-being of the community, the ultimate goal or telos of the society, in which all the stakeholders of the corporation can provide opportunities for people to participate in the business environment of a free economy. For more information about Mr. Christos Papoutsy, his schedule of free lectures, or to read his other articles on corporate social responsibility and business ethics, visit the About Us, Business, or Business Ethics sections of the Hellenic Communications Service (HCS) website, http://www.helleniccomserve.com or the web pages of the Christos and Mary Papoutsy Distinguished Chair in Ethics at Southern New Hampshire University at the URL http://www.snhu.edu/papoutsy.html. HCS readers who enjoy this article may wish to read "Corporate Social Responsibility: Is Moral Capitalism Possible?" and "Business Institutionalization Promotes Excellence, Combats Corruption." Mr. Papoutsy welcomes comments and can be reached via e-mail at the address papcoholding@papcoholdings.org. HCS readers may wish to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com  |