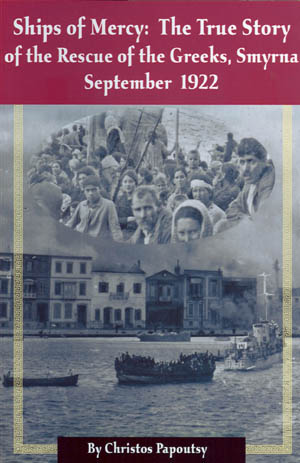

The Armenian quarter fell first as it was sealed off and set on fire; the looting, fires, rapes, and murders spread with few non-Turks spared; soon the city was an inferno with men, women and children fleeing to the only place that they could go-- toward the sea. Perhaps as many as 300, 000 were packed in the narrow quay, hoping and praying that the ships in the harbor would rescue them as they huddled in terror of the advancing, fiery death. This is the point where author Christos Papoutsy enters the story.

The story of the rescue at Smyrna is not clear because of the chaotic uncertainty accompanying the events. Low estimates put at least 120,000 killed: butchered on the spot; rounded up and shot in batches; shot individually; shot as objects of "target practice;" roasted by fire; or raped and killed. Many died from hunger, exhaustion or injuries; crowds crushed and trampled some; some threw themselves into the sea and drowned in the vain attempt to reach a rescue ship; and yet others simply gave up all hope and expired. Buildings were set on fire, records lost, food and goods confiscated, helpless individuals robbed of everything, and marauding bands turned loose to loot, pillage and slaughter. For one month the densely packed, panic-stricken crowd subjected to continuous deprivation, danger and death huddled in on the quay hoping for rescue. Eventually thousands were rescued. But how were they rescued? History is not clear.

This is the task author Christos Papoutsy sets out to address. In a very carefully researched book, Papustsy relies on naval records, government reports, documents from churches and relief organizations, contemporary newspaper releases and eyewitness accounts to tell the awful story of the destruction of Smyrna and the belated, but heroic rescue effort. Historical accounts of the destruction of Smyrna tend to either gloss over facts of the rescue or else are rife with inaccurate information. This small volume goes a long way in setting straight the account.

In the first chapter, Ships of Mercy presents a brief historical overview of Smyrna, interweaving accounts of its ancient and historical roots and its twentieth century position as a commercial and cultural hub. The second chapter is more sober. In sickening detail the destruction of Smyrna is told. This chapter alone makes it important to remember Smyrna because it vividly reminds us that our darker side as a species is not far below the surface. It is hard to comprehend the moral and psychological flaws that made it possible for individuals to commit such atrocities in the name of nationalism, religion, ethnic differences, historical antecedent, military necessity or material gain. What we call "civilization" is, indeed, a very thin veneer.

But the destruction of Smyrna is important to remember because the events and rescue also show the better side of our species. Individuals flouted danger and hardship to help others and gave all that they could with no other motive than to respond to those in dire need. Perhaps the most remarkable story is that of Asa Jennings, an unassuming mid-level Y.M.C.A. functionary who stepped up amid the carnage and took action to rescue thousands from the quay. He cajoled, bribed, bluffed, threatened, and appealed to Italian, French, American and Greek in order to secure available sea transport, and he helped to gain assurance from the Turks not to block the exodus. Perhaps his most crucial accomplishment was convincing the Greek government in Athens, which was itself caught in the turmoil of political crisis, to throw its fleet of twenty ships into the rescue effort and the Turks to accept the fleet, minus the Greek flag. The American counsel general George Horton threw his weight into the rescue effort, and captain Powell of the American destroyer flotilla and captain Theophonitis of the Greek ship Kilkis were instrumental to the rescue.

Governments were frozen in inaction, stymied by the inertia of indecision; what is remarkable about the rescue effort is the initiative of individuals who with no official authority assumed leadership roles, made critical decisions and organized and oversaw the rescue effort. Many assisted with the relief effort, organizing, loading ships and administering to the needy; many more received the refugees and helped to house, feed and clothe the needy and ease the pain and trauma of the catastrophe. The rescue at Smyrna shows that individual acts do count.

Chapters three through five cover the rescue efforts. The remarkable work of Asa Jennings and others is chronicled in detail. It is a heartening story, muted by the surrounding suffering. In chapter four author Papoutsy assembles a number of resources to chronicle the rescue effort not only in Smyrna but throughout the coastal area where Greek villages were being burned and desperate citizens were fleeing. An account of some of the relief efforts after the rescue is given. Perhaps author Papoutsy's most solid contribution to historical research is his account in chapter five of individual captain and ship logs. Through detailed research the author provides a revealing story of the interaction between the different rescue ships, individuals involved in the rescue and the worsening situation. He puts to rest erroneous accounts of the tragedy and corrects misunderstood events.

In chapter six, author Papousty corrects what has become perhaps the greatest misconception: Allied ships stood idle and even thwarted the efforts of fleeing Greeks to escape, while at the same time, the story goes, Japanese ships came to the rescue. Through careful research of naval records, Papousty finds that no Japanese ships were even in the surrounding area at the time of the events. Contrary to mistaken beliefs, it was mainly Greek, American and other European ships that took decisive action.

There was plenty of blame to go around for the tragedy at Smyrna. The Italians helped to provoke events by driving northward from the southern occupation zone they were given in the hope of gaining control over more former Ottoman territory. The British, in the expectation of blocking the Italian advance convinced the Greeks that it was in their interests to occupy Smyrna and beyond. Hower, they failed to provide expected support at critical junctures. Lured into occupying Smyrna and blinded by false hope, the Greeks entered into a military adventure with little possibility of emerging victorious. Colonel Ioannis Metaxas, the hero of the Balkan Wars, warned Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos that any military incursion into Anatolia would end in disaster, but Venizelos plunged ahead despite the lack of sufficient financial support, an ill-prepared and equipped army and fragmented and insufficient national support. The change of government under King Constantine was equally disastrous, with leaders playing a bad hand badly. Then, too, as the Greeks confidently advanced into the interior, along with armed Armenian bands, they razed Turkish villages on the way and committed their share of atrocities. The difference is that the scale of slaughter and destruction by the Turks was so much greater in Smyrna and throughout Anatolia. [ed: see dissenting comments under Publisher Responds to Comments and Reviews of Ships of Mercy.]

The Allies betrayed the Greeks. Once the conflict got out of hand, the Allies stood by and did not offer the Greeks help in a situation in which they shared a large part in which they shared a large part. Frozen by the inaction of self-interest, the Allies lost the collective opportunity for quelling a conflict that was to have long-standing adverse international ramifications. The Italians, French and British made a mockery of Allied solidarity. The Italians and much of the Jewish population in Smyrna served the Turks and thus were largely spared the destruction and slaughter. The French, Russians and Italians aided the buildup of Kemal's army. The French, wanting to solidify their hold on Syria, worked behind the scene to curry favor with Kamal, and the British, deciding that the potential oil deposits in Iraq were more important than their promises of support to the Greeks in the end withheld diplomatic and financial support. One lesson that clearly emerges is that there is very little morality or honor in power politics, only self-interest.

Rescue from Smyrna, however, did not end the suffering of refugees. Escaping with barely more than the clothes on their backs, the refugees struggled to reclaim their lives in the quickly assembled camps established in Mytilene, Salonica, Kavalla, Chios, Euboea, Crete and numerous towns and villages throughout the islands and mainland that opened their arms to fellow Greeks in need. And non-Muslim civilians fleeing to the coast to escape the marauding Turks quickly joined the refugees from Smyrna. Soon the refugee tide reached over 1,400,000, stressing the already short supplies and capacity in the numerous makeshift refugee camps. Sickness, hunger and death were common. In chapter 7, author Papoutsy recounts the plight of refugees and the international response. The following chapter gives a succinct account of the disgraceful Treaty of Lausanne and the sell-out of the Greek cause by the Allies for commercial and political gain in the region. Chapter 9 focuses specifically on the work of Asa Jennings who by the force of his own convictions played such an instrumental role in mobilizing the rescue from Smyrna. His actions helped to save over 300, 000 men, women and children.

In a short, insightful chapter, author Papoutsy concludes by probing the question "Why has so much of the history of the tragedy at Smyrna been either lost or clouded in misinformation?" "How could the world forget?" he queries. This small volume will help us to jog our collective memories. It is a quick, extremely well documented read. It is a story that needs to be remembered.

Dennis R. Herschbach

University of Maryland

College Park