|

|

|

|

|

"I am proud both as Prime Minister and Minister for Culture of Greece to be able to look forward to the opening of the New Acropolis Museum - a museum designed to shelter and exhibit our unique world of heritage in a setting of international museological and architectural standard. In particular the outstanding design of the glass-walled Parthenon Gallery, purpose built for the exhibition of the Parthenon Marbles provides the optimum environment in which the sculptures of the classical Parthenon can be displayed and a sound basis for Greece's discussions with Great Britain on the question of their reunification." - Kostas Karamanlis Prime Minister |

|

|

In 1997, three years before the commencement of the international competition to select a design team for the New Acropolis Museum, an extensive and systematic archaeological excavation began on the building site in Makryianni Street, in order to investigate archaeologically the area chosen for the location of the New Museum. The finds were abundant on the north and west sides, in contrast to the rest of the site, where facilities for the Gendarmerie camp, such as underground bunkers and fuel tanks, had been installed. The excavations brought to light a densely built section of ancient Athens, with remains from successive building phases, the best preserved of which were those dating from Late Antiquity. The antiquities determined the architectural plan of the base of the Museum. In those places where no ruins or very few existed, it was decided to construct the levels below ground, which occupy much less than half the built horizontal surface of the building. A spacious columned hall, with openings in the roof, so that the ruins are visible in daylight from the ground floor, is erected over the excavated area. The ancient street arteries dictated the architectural zones in the lower part of the Museum, linking it with the excavation. This is in contrast to the crown of the building, where the Parthenon Gallery is orientated differently, parallel to the ancient temple on the summit of the Acropolis. The exhibition entitled "The Museum and the Excavation" has been mounted in order to prepare the final presentation of the finds in the excavated site. There is experimentation with construction materials, access for visitors, the thematic organization of the archaeological finds and the aesthetics of display, all of which are intrinsically linked to the manner in which the excavation is incorporated into the Museum's architecture. The excavations were funded by the Organization for the Construction of the New Acropolis Museum and were supervised by the First Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities. Dimitrios Pandermalis |

|

|

The Exhibition

|

|

|

The site on which the New Acropolis Museum is being constructed lies in an area whose urban tissue goes back to the fifth century BC and which was inhabited continuously until the twelfth century AD. Excavations have revealed a typical ancient neighborhood of Athens, with many building phases. Hitherto unknown streets with their water-supply and sewerage networks were uncovered, as well as houses of various periods, with their courtyards, wells and cisterns, large urban villas of Late Antiquity with their mosaic floors, public and private bathhouses, sanitary installations, workshop units of different sizes and even graves. Large numbers of objects were also recovered, which give an insight into the resident's habits and the way in which they conducted their transactions. The exhibition is organized in 12 thematic units, each one displaying artifacts representing specific facets of the private and public life of the residents in this neighborhood. |

|

The style of presentation and the materials used (the sand ground cover, wooden walkways, workshop-type metal cases) have been chosen to immerse the visitor into an excavation-like atmosphere. The exhibition is addressed to the general public. Its aim is to make the visitor a participant in the process of reconstructing and understanding a culture which although seemingly remote, is in many ways close to the patterns of our own contemporary lives. |

|

|

Buildings |

|

| The first unit focuses on the buildings (houses, baths) and their decoration. Marble architectural members - column bases and capitals, epistyles, relief slabs and terracotta antefixes are presented, as well as mosaic floors, clay pipes, structural elements of the baths, marble table supports, as well as the bust of the philosopher Plato, which might have decorated one of the residences in the he area in Roman times. |  |

|

Workshops |

|

| In certain cases, some rooms in the houses with facades onto the street were used as shops or workshops. In other cases, the workshops were larger, independent structures. Among the most important are the coroplastic workshops of the second century BC which produced terracotta figurines, the marble workshops of the first century BC to the first century AD in which statues and vessels were sculpted, the metal and potters' workshops of the same period, as well as the organized craft-industrial units as for example pottery and metalwork of Byzantine times. |

|

|

Economy and Trade |

|

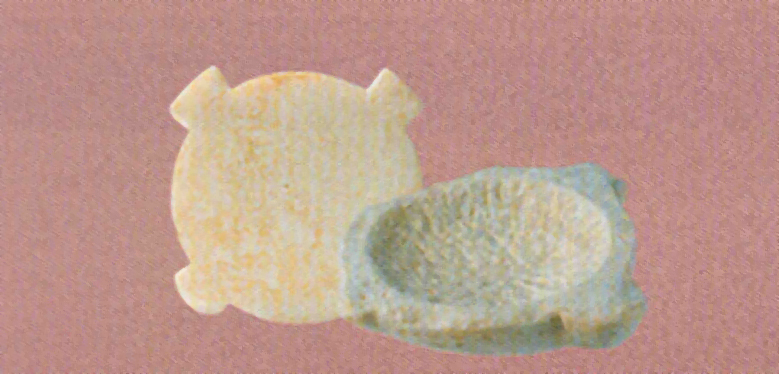

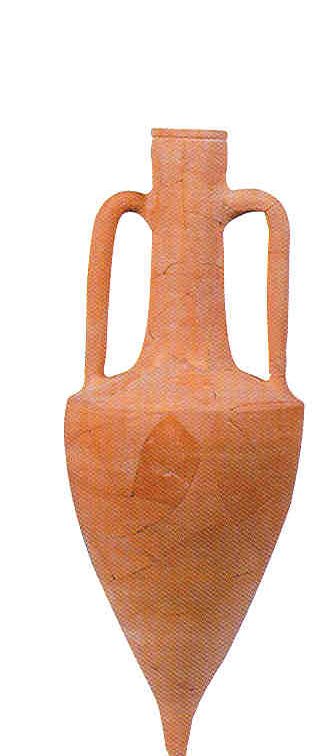

| The numerous amphorae, many of them with provenance stamps on the back of their handles, the marble and lead balance weights and hundreds of coins all bear witness to a thriving economy and trading transactions. The lead tokens, which resemble small coins, were used in much the same way as today's coupons, while the clay seals in bronze seal boxes and the Byzantine lead seals secured the confidentiality of official and private documents. |

|

|

"Egainia" |

|

| The laying of the foundations of a house, a workshop or a shop was frequently accompanied by a small sacrifice, the engainion (ritual pyre). The ritual included the burning of animals and birds in a small pit, and the depositing of clay vases, often miniature ones. The sacrifice was intended to appease the spirits of the Underworld, to ensure that these protected the owner and averted evil. The custom, which was particularly popular in Classical and Hellenistic times, lived on into Late Antiquity. |

|

|

Water - Wells and Cisterns |

|

| The houses in this area were supplied with water from wells and underground cisterns in which rainwater was collected from the roofs. The inside of the wells was often lined with clay walls, notched at intervals in order to facilitate the placement of items and access for construction and cleaning. The mouth on the surface of the ground was surrounded by large marble slabs, on which the wellhead was set. These slabs were frequently framed by the foundation of wooden scaffolding for the pulley wheel. Many abandoned wells were used as "rubbish pits", for discarding useless objects. Excavation of these yielded numerous clay vases, many intact, and various other artifacts. |

|

|

Worship |

|

| In Antiquity people worshipped not only publicly in temples, but also privately in specially arranged areas of the house. Objects such as small alters, statuettes, figurines and lamps with representations of deities attest to the cults of Aphrodite, Apollo, Dionysos, Artemis, Asklepios, Hygeia and Hekate, as well as of Deities of Eastern provenance, such as Cybele, Isias and Zeus Heliopolites. The transition to Christianity is reflected in the lamps with Christian symbols, in the neck crosses and in the ampullae containing consecrated oil from the sites of saints' martyrdoms or water from the River Jordan. |

|

|

Lamps and Lighting |

|

| Terracotta lamps were the most widespread means of providing lighting in Antiquity. Simple or elaborate, plain or decorated, they were filled with olive oil and provided the necessary illumination during the hours of darkness. From Roman times, the upper part of the lamps bore representations drawn from the domain of cult or of daily life, or the animal and plant kingdom, while the base was frequently inscribed with the signature of the craftsman or of the owner of the workshop in which they were made. |

|

|

The Kitchen and its Equipment |

|

| A large number of vessels, usually of clay, was used for the storage, preparation and cooking of food. Vases for water and for wine and other products (amphorae, jugs, pitchers), for oil (lekythoi), small unguentaria for condiments, basins, mortars and pestles for food preparation, deep and shallow pots (chytres, lopades) for cooking, grills for broiling, and frying-pan vessels (seisones) for roasting nuts and fruits were used. The food was cooked on hearths and in ovens as well as in portable braziers, which were also useful for heating the house. |

|

|

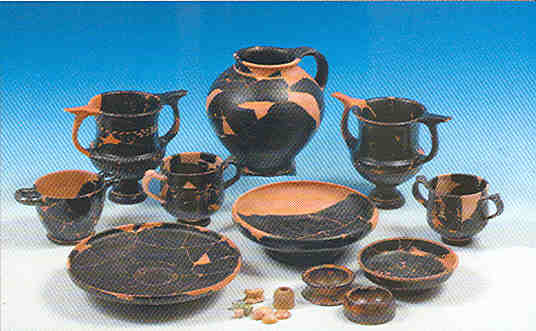

The Symposio |

|

| At family meals and at men's dinner parties (symposia) a large number of table vessels was used: plates of different shapes and sizes, including fish plates and bowls, for the food, the sauces and the spices, jugs, pitchers and cups (kylikes, kantharoi, skyphoi) for the wine. At symposia, conversation, music, dance, song and other forms of amusement accompanied wine drinking. The courtesans (hetairai), flute playing women and dancing girls were the only women permitted to participate. The symposiasts often played the popular game of cottabus with their cups, or other gambling games with counters, dice and knucklebones (astragaloi) |

|

|

From the World of Women |

|

| In contrast to men, most women spent their time within the confines of the home. Objects such as needles and bone spools, spindle whorls and loom-weights point to their occupation with spinning and weaving. Bronze mirrors, clay or glass perfume bottles (lekythoi, alabasters, askoi), stirrers, spoons, spatulas and small marble basins with finger pestles for preparing cosmetics and perfumes, containers for cosmetics and jewelry bespeak care over their appearance. Bone or metal pins held their garments and their hairstyles in place, while earrings of gold or bronze, necklaces and rings set with semiprecious stones were the jewelry worn by women of all social classes. |

|

|

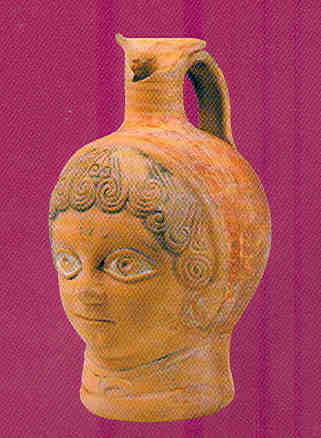

From the World of the Child |

|

| The life of children in ancient Athens was little different from that of children today. Babies were fed with feeders and were soothed with rattles, girls played with dolls, miniature vases or a terracotta horse on four wheels that they pulled with a string. Older boys, and sometimes girls, attended school. They wrote with a stylus on tablets coated with a film of wax, or on sheets of papyrus with ink from an inkwell. Objects such as clay vases in the form of a boy's head as seen in the exhibition were associated with rites. The marble child's heads come from statues which parents offered to the deities that protected their children. |

|

|

Graves |

|

| At various times in its history, this area was also used for burial of the dead. Most of the burials were of children and date either from very early times, when the site had not been settled systematically, or from very late times when the area was in decline. The dead were furnished with grave goods - usually clay vases, terracotta figurines and simple jewelry - reflecting the funerary customs and the beliefs about life after death, which prevailed in each period, as well as the social and economic status of the deceased. |

|

|

(Posting date 29 December 2006) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|