|

|

|

The Coup at 40 The Press Fights Back (Part 2 of 3) |

|

| Forty years ago, a group of colonels suspended parliamentary democracy and press freedom in Greece. Their dictatorship would last seven years and end with the disastrous invasion of Cyprus. In the fourth installment of a five-week-long series of eyewitness accounts now out of circulation, Robert McDonald explains how journalists fought a guerrilla war against censorship, and how one newspaper that tackled the dictators head-on was made to pay IF EVIDENCE were needed of just how little sympathy the colonels commanded after 2 1/2 years in office, the reaction of the press to the abolition of prior censorship provided a dramatic demonstration. Overnight, the perpetual promotion of the regime |

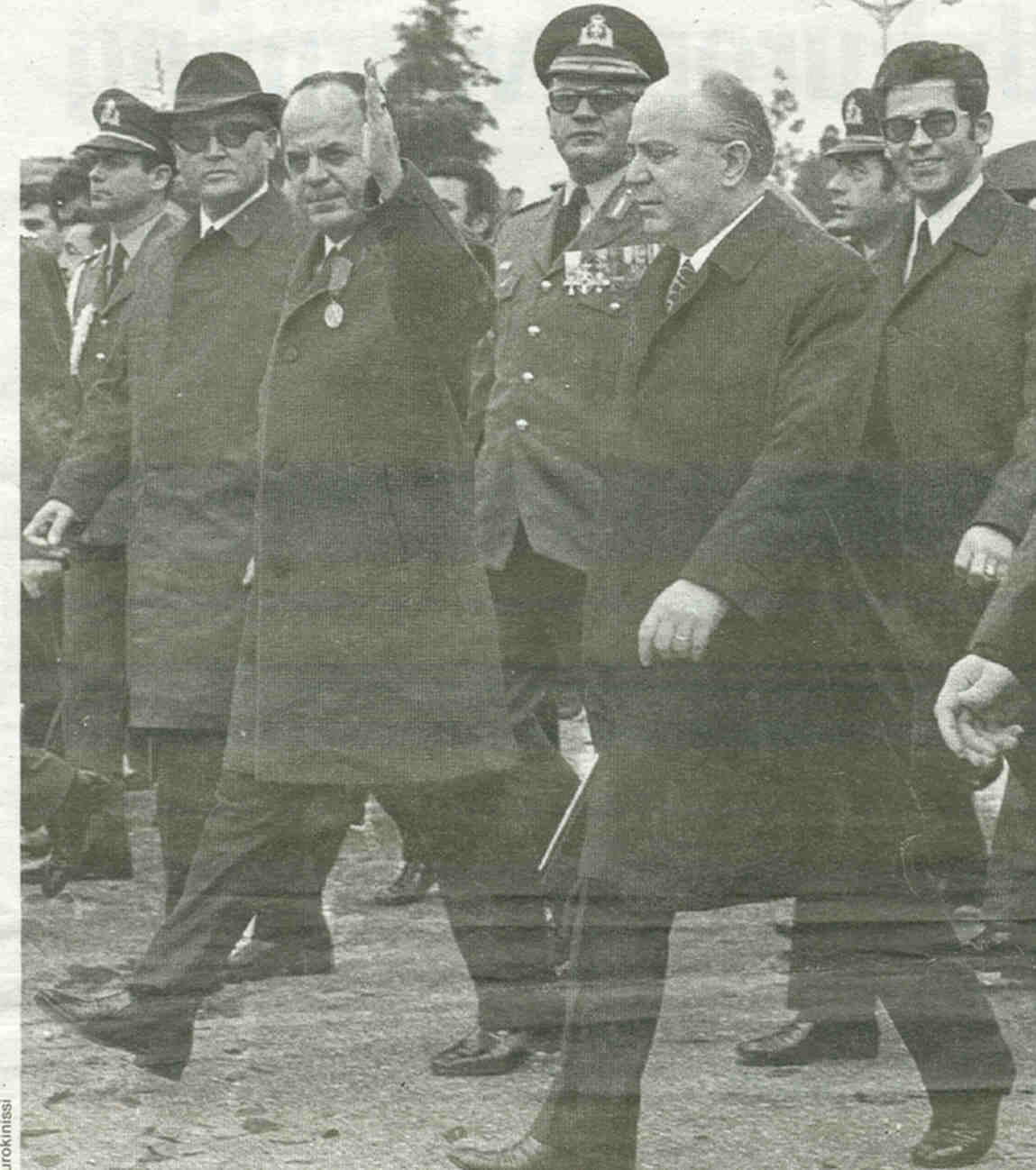

Colonels George Papadopoulos (waving) and Nikolaos Makarezos (looking down) |

| gave way to hard news coverage, much of it implicitly critical. It was far from full press freedom, for the prohibition remained against attacking the present regime or promoting the former, but the new system did allow the reporting of a wide range of subjects that had previously been suppressed. In essence, it permitted factual accounts of most events, provided that neither their subject matter nor the manner of their recounting constituted a direct political attack on the regime. Thus, for example, it was possible to cover a resistance bomb attack, provided the story confined itself to the facts of the detonation of the explosive device, the damage, the injured, etc., without saying who claimed responsibility for it or what their motives were. However it was not permitted to report resistance tracts because of the tenor of their contents. Transcripts of the trials of resistance workers with their horrific allegations of torture were permissible but examination of the political rationale for the defendants' actions or editorial demands for official inquiries into the claims of maltreatment were not. Statements critical of the regime, either by individuals or institutions could not be reported but complaints about specific acts of the administration occurring as a consequence of the dictatorial nature of the regime could be, provided that no derogatory conclusions were drawn from the facts. It was a situation fraught with pitfalls for journalists because of the multitudinous ambiguities, but it was one from which they were able to make much mileage because of the subtlety of political appreciation of their readers who took volumes from every nuance. Opposition was expressed obliquely by playing up the activities of groups opposing dictatorships abroad in Iberia and Latin America. American reverses in the Vietnam war featured prominently because, as the United States was deemed to be responsible for the colonels, anything seen to diminish American prowess was construed as a blow against the dictatorship. Liberation struggles, urban terrorist activities, hi-jackings all got good play, not because they were condoned but because of the political upheaval they implied. Constantine's every move was chronicled; two papers even ran extensive accounts of the events

of the counter coup. After months of official silence about the increasingly troubled situation in Cyprus, there was now extensive coverage.

The papers constantly strained at their limitations. One favorite device was the trick headline, such as eight columns of screaming woodtype declaring, 'The dictatorship is rapidly receding' coupled with a tiny kicker reading 'in Spain'. Another was to reprint critical comments by foreign political figures. This could be done only in those instances where it was nicely judged that the diplomatic embarrassment to the regime of being seen to suppress the remarks would be greater than the domestic political damage of allowing them to appear. France, for instance, was, for pragmatic reasons of trade, one of the few western European countries not overtly critical of the colonels. Thus, when receiving a new ambassador, French president Georges Pompidou made a one-line passing reference to possible political developments in Greece, it was bannered in Athens next day as 'Insinuations by Pompidou on evolution.' |

|

|

Similarly a transcript of U.S. Congressional hearings urging restoration of parliamentary government appeared because at the time the colonels were working to end an American arms embargo and to have intervened would have been counterproductive. Regular denunciations of the regime by British, German and Scandinavian parliamentarians went unreported. The Lambrakis papers indicated their opposition by refusing to publish editorial commentary. To abide by the rules |

Christos Lambrakis, publisher of Ta Nea and To Vima, did not suspend publication as Kathimerini had done immediately after the coup, but refused to publish editorial commentary |

| and to criticize administrative actions without drawing political conclusions, they argued, was only to give comfort to the regime. In a boxed item on the front page of Vima the day that prior censorship was lifted, Lambrakis Wrote, 'We consider that there is not the scope permitting us to write political articles. 'We will thus abstain from all political commentary until the lifting of the state of siege re-establishes all political and individual liberties.' Vima and Nea did, however, become masters of the art of critique through reportage. For example, one day they would report that certain individuals were denied passports; the next they would publish the relevant legislation setting out the legal criteria for them to be granted. Soon there would be letters from others who had been refused papers. The reports never stated that the action was political but it was obvious and very quickly the papers could create what amounted to a campaign of complaint without a viewpoint ever having been-expressed.". Eventually Yradyni encroached on the forbidden territory of political commentary when it offered a forum to retired Colonel Dimitrios Stamatelopoulos, a former member of the junta who had broken with his colleagues over their efforts to create a new political order. He favored quick refurbishment of democratic institutions and restoration of a purified parliamentary government. Athanassiades gave Stamatelopoulos carte blanche to write an article for the Saturday paper whenever he wished on the subject of his choosing and at whatever length he liked (each one was worth an additional 30,000 copies in circulation). They were rambling, turgid texts which reiterated Stamatelopoulos' fears that 'a chapter might become a 'tome,' They had an unnerving effect on the regime because they represented a worm in the bud. More importantly, his association with the paper gave it an immunity from overt persecution and afforded protection to other, intelligent commentators, such as political and diplomatic editor Vassos Vassileiou who made sophisticated critiques. Vass. Vass., as he was known, regularly wrote subtle front-page editorials in which he would analyze the discrepancies between government policies and pronouncements and regime practice. He was particularly adept in detailing how statutes produced to flesh out the constitution frequently curtailed in their details liberties set out in the general principles of the larger law. Vassileiou probably did more than any other single individual to destroy the regime's efforts to create a veneer of democratic respectability. The fate of Ethnos The colonels retaliated against the press by using covert measures of economic punishment. Circulation was interrupted. Newsprint taxes were applied in proportion to circulation which hit hardest at the popular opposition papers. State advertising was placed selectively and loan facilities which required government authorization were denied to opposition publishers. The revenue department was used to make harassing inspections and to levy punitive sums of tax. But the colonels hadn't counted on Ethnos, a paper which was effectively bankrupt and which, as a consequence, decided that it could afford to risk its all in political defiance of the regime. Founded in 1913, Ethnos was a family business owned 50% by Constantine Nicolopoulos, son of the founder, 30% and 20% respectively by his first cousins Constantine and Achilles Kyriazis. Nicolopoulos was a businessman, Achilles a translator. Constantine Kyriazis was the journalist, active in the day-to-day operation of the publication. The newspaper was liberal by tradition and in the early days of the dictatorship as one of those papers which it was politically unwise to be seen reading. Its circulation dropped by more than half between April and May 1967 and the paper lost so much money that in August that year the partners agreed that they should cut their losses by declaring bankruptcy. The regime, however, forced Ethnos to take a four million drachma loan from the National Bank of Greece and to accept a government nominee to oversee publication. This was former city editor Andonis Andonikakis, a man described by Kyriazis as 'an ex-communist who had become an addict of the dictatorship.' Kyriazis boycotted his own office for nearly two years as a sign of protest. Under Andonikakis' guidance, the paper staggered on in undistinguished fashion gradually losing more and more money until, by the time censorship was lifted, the paper was once again on the brink of collapse. Kyriazis says the government would have provided more funds had the paper been prepared to 'genuflect' but the partners refused and again contemplated bankruptcy. This time, however, Kyriazis argued that they should see whether they might reverse their fortunes by taking what advantage there was to be had from the limited freedom of expression. He returned to the paper on November 1,1969. Finding staff that had not been paid their salaries for two weeks, he told them there was 'no money, only the will to fight the dictatorship.' Everyone, he claims, agreed to work on. In the beginning the approach was tentative, with opposition confined to reprinting the texts of others such as Council of Europe deliberations on Greece. But, by the new year, the newspaper was itself generating opposition material. It openly challenged the regime's press policy in a bold page one editorial on January 10, 1970. 'We call on the government to decide. If it thinks it feasible and expedient, let it go ahead with its experiment on press freedom - courageously, sincerely and without hesitation. If not, let it reimpose preventive censorship. It would be preferable and braver.' In February, it launched a series of hostile features, one serious, involving well-known writers being interviewed about the degree of freedom of expression then current in Greece, another lighter, in which public figures were asked to say what they could do 'If I were a dictator.' The paper dredged up and ran an Athenian law from 335 B.C. which urged citizens to slay all tyrants. |

|

|

The government reacted by diverse means. There were private threats that they would close the paper and there was interference with provincial circulation so extensive that in some places it was impossible to buy the paper for days on end. In one town at least, readers were told the paper had ceased publication. Overall, the rise in Ethnos' circulation was inexorable, climbing 139% in the short space of seven months. Then, the government called its imposed loan. The first installment of 700,000 drachmas was declared due on March 14,1970 and a court order was obtained saying that equipment could be auctioned if payment was not made. Only minutes before the auctioneers were due to move in, it was met with the proceeds of a whip-round among the publishers' wealthier friends. Finally, the Internal Revenue |

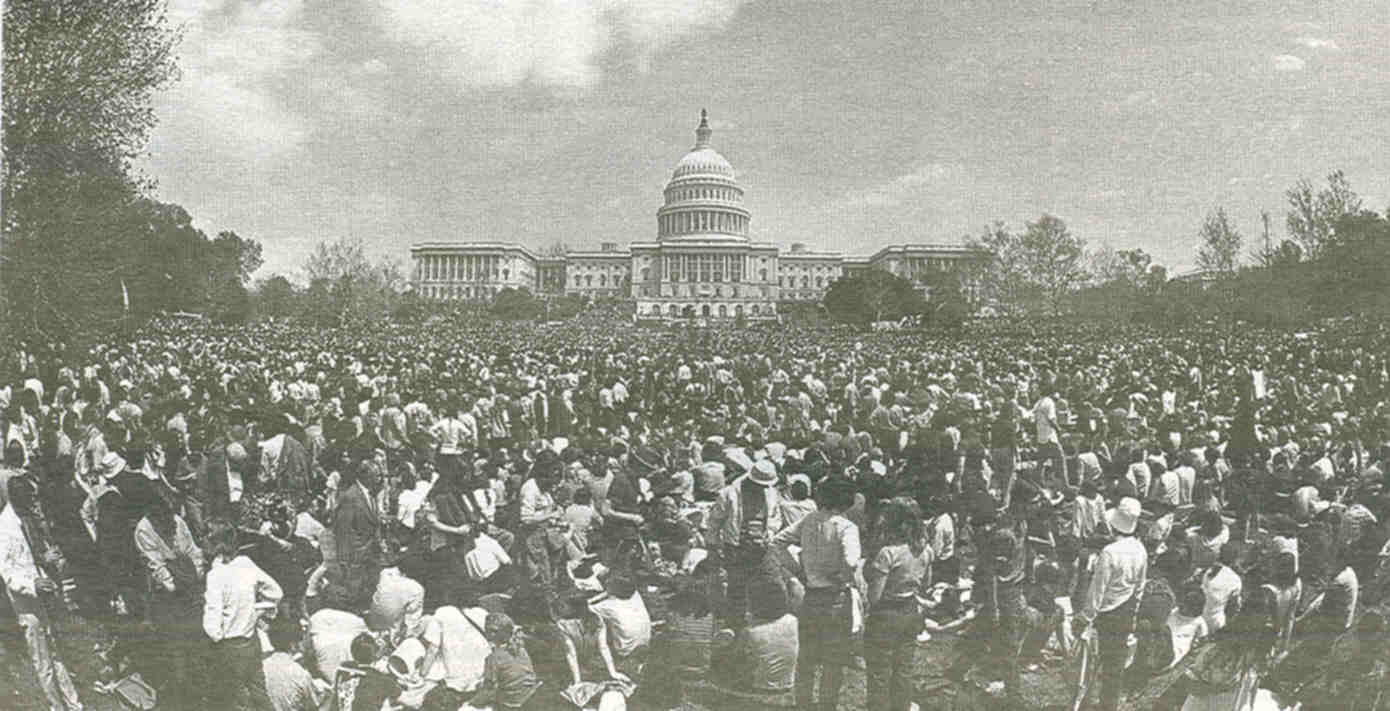

Vietnam war protesters march to the Capitol on 24 April 1971. Greek newspapers tried, under censorship, to criticise the colonels through foreign coverage. American reverses in the Vietnam war featured prominently because, as the U.S. was deemed to be responsible for the colonels, anything seen to diminish American prowess was construed as a blow against dictatorship |

| Service was called in to do a detailed audit following which it was alleged that the paper had practiced a number of administrative irregularities. It was assessed back taxes totalling some fourteen mi1lion drachmas. From that moment on Ethnos was financially lost and effectively dead. In such hopeless straits, it became reckless and the regime finally resorted to the naked force of martial law, although not without further warnings. The Athens Military Commander called in first the paper's editor, Ioannis Kapsis, and then the senior partner, Constantine Nicolopoulos, and told them that if they did not cease their opposition forthwith, they would be brought before a military tribunal and be found guilty of press offenses which would carry the maximum five-year sentence. When the paper continued, the threat was methodically carried out. The pretext for the prosecution was an interview with the former Center Union politician, John Zigdis, which the paper published on March 24, 1970. It recommended the formation of a government of national unity in Greece to deal with the burgeoning political crisis in Cyprus. In the weeks immediately preceding, there had been an attempt to assassinate President Makarios, in the wake of which Cyprus Interior and Defense Minister Polycarpos Georgadjis had been murdered. It was widely rumored that the colonels were hatching a coup. Zigdis had called for the formation in Greece of 'a political government, fully trusted by the Greek people... A government of national unity should face this critical time.' It was the sort of open challenge to the regime which was absolutely forbidden. The three proprietors; the editor, Zigdis and 82-year-old Constantine Economides, honorary director of the paper, were arrested and charged under an article of the Penal Code which fell under the aegis of the martial law. This was Penal Code Article 191 concerning the dissemination of false information liable to cause anxiety to the public. They were also charged with breaching martial law orders by making 'anti-national propaganda.' The trial, on March 31 and April 1, was a legal farce. The prosecution made no serious effort to mount a case and, as the charge was a political one, the defense treated it as such, calling twenty leading figures of the former political world, headed by deposed Premier Panayotis Kanellopoulos and centrist George Mavros. The confrontation turned into a political slanging match at one stage of which an officer of the military tribunal leaned forward and barked, 'Zigdis and the others won't live long enough to see elections again.' At two a.m. on April 2, the tribunal handed down its verdicts: Kapsis five years, Zigdis four and a half years, Constantine Kyriazis four years, Nicolopoulos and Achilles Kyriazis three years and Economides thirteen months, these to be accompanied by fines ranging between lOO,00 and 200,00 drachmas. It spelled the end. From their prison cells on April 3, the proprietors announced the closure of Ethnos. That this had been the intention of the regime from the outset was reinforced by the substantial reduction of the sentences when appeals were heard the following September: Kapsis twenty months, Constantine Kyriazis fourteen months, Nicolopoulos and Achilles Kyriazis thirteen months, and Economides acquitted. The appeal hearing was highlighted by an incident which epitomized the farcical tone of the entire affair. One of the prosecution witnesses, a trade union official, told how he had read the report in Athens at 8.30 a.m. before setting out for Patras. He said that when he arrived there, he found a number of people anguishing over the article. Ethnos was an afternoon paper which did not come out till noon. With time off for good behavior, the four jailed newspapermen were free by May 1971. Zigdis, however, refused to recognize the court's right to have tried him in the first place and would not appeal. He stayed in jail until January 1972 when the regime released him, without an appeal, on the grounds of ill health. Kyriazis says that, while imprisoned, the partners were approached by an employee of long standing, acting as an emissary of the colonels, with a new offer of a loan if only the paper would re-appear without attacking the regime. This was refused. The proprietors were determined that if the paper couldn't operate on ' their terms, it wouldn't open again. By the time, they were released from prison, staggering debts of twenty-seven million drachmas had accumulated and so, finally, in June 1971, Ethnos was put into liquidation. The beginning of the end for the colonels The treatment of Ethnos served as an object lesson for the rest of the press, demonstrating just how ruthless the regime was prepared to be if it felt threatened. Editors took the message and cautiously curbed their criticism. The tone of the papers for a while after was one of grudging sullenness. To chivvy them along, Papadopoulos introduced as Undersecretary the propagandist, George Georgalas. In his capacity as a psychological warfare specialist prior to the coup, he had been associated with Papadopoulos at the Greek Central Intelligence Service (K.Y.P.) and probably advised the junta on how to prepare public attitudes for the takeover. His approach to the press was coldly calculating. Using classical tactics of divide and rule, he crooned a siren song designed to persuade journalists to abandon their loyalty to their proprietors and to ally their interests with the Revolution. 'I believe that the press problem in Greece is mainly a publishers' problem and it is my conviction that a way must be found to draw a distinction between the responsibility of journalists and owners.' |

|

|

Prior to the coup, he said, publishers had been able to make and unmake governments. Their opposition to the Revolution was founded in their desire to reassert that influence. In this, they exploited their employees. The Revolution wanted a 'true democracy which means that no individual or group will wield as much power as that wielded by the press before the Revolution. 'In the beginning, he said, the regime had made a mistake; it had tended to identify journalists with press enterprises some of which had played a negative role.' Now it realized that 'a free, responsible and conscientious journalist cannot but agree with the great national and regenerating endeavour of the Revolution.' The government was therefore 'studying ways to prevent publishers from dismissing journalists who refuse to act against their consciences.' |

King Constantine initially gave the colonels political legitimacy by blessing the Kollias government; but in December of 1967, barely eight months after the coup, he mounted a failed effort to unseat them. It failed, but the press gave it extensive coverage as an indirect form of protest |

|

These measures were, he said, only 'the first installment;' if journalists cooperated, we shall think of other things as well.' His approach revealed a fundamental contempt for the press which he thought could be bought by such mean commerce. It permeated all his thinking about journalism. Asked why newsmen were not allowed to buy off prison sentences, even for petty offenses, he railed about sensationalism and distortion and replied, 'if a merchant can be jailed for selling shoddy goods, why should a journalist not be jailed for selling shoddy ideas.' His alternative, spelled out in draft legislation on the profession of journalism published in August 1971, would have made journalists as dependent upon the state as he contended they now were upon their employers. It called for them to sign loyalty oaths similar to those required of civil servants, laid down a code of ethics which said that journalists should 'serve the interests of the nation' and made them subject to discipline administered by government appointed committees. Georgalas argued that this code of ethics, by being enshrined in law, gave journalists for the first time a legal means with which to confront their employers. |

|

|

In a further effort to curb the hegemony of the Athenian publishers, Georgalas produced legislation to strengthen provincial publications. It provided for indirect central government subsidies to regional daily newspapers and the establishment of a regular news service for the provinces to be provided by the government-controlled Athens News Agency. The wire service was inaugurated on June 1, 1971, but, although the legislation to provide the financial aid was actually gazetted, the decision of the Prime Minister necessary for its implementation was never forthcoming. During Georgalas' tenure, pressures on the press showed scant respect for the rule of law. The Lambrakis group was particularly hard hit. George Romaios, editor-in-chief of Vima, disappeared on March 19,1971 and was missing without trace for several days before the military police admitted that they |

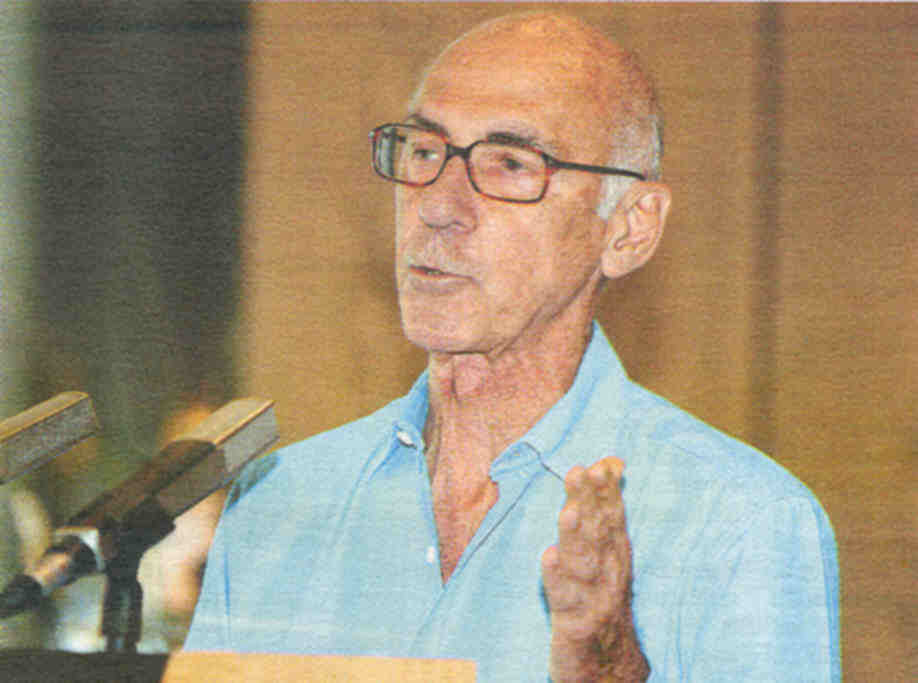

Former Centre Union deputy Ioannis Zigdis caused the ire of the dictators when he published an editorial in the newspaper Ethnos in March 1970 calling for the formation of a government of national unity in Greece. |

| were holding him on suspicion of being a member of Andreas Papandreou's Panhellenic Liberation Movement. Romaios claims that 90% of the questions asked during his interrogation had nothing to do with his alleged resistance but with stories he had run. According to Vima's publisher, Leon Karapanayotis, 'It was the perception of everyone in the office at the time that Romaios was being held hostage for our good behavior.' He was released after five months detention without charge the day after Georgalas left office. Other Vima and Nea personnel were periodically called in by the Military Police (E.S.A.) and had Romaios' example to contemplate while awaiting interrogation. Karapanayotis suffered the experience several times. 'You would be brought in and Theofylloyannakos would scream and shout at you. Then you'd be locked in a room for a couple of hours until you thought you were under arrest when, suddenly, they'd let you go. The next time you'd be put in a room and curious characters would be brought in to stare at you. Hadjizisis would say, "You don't know Mr. Mallios? Mr. Babalis? Let me introduce you," and then they'd all go away again.' (Theofylloyannakos and Hadjizisis were both Military Police officers with public reputations as torturers: Mallios and Babalis were similarly notorious security police officers.) Ministers would telephone the paper 'to make sinister noises' about the way specific stories had been played and anonymous threats were made to individual journalists. Court reporter Nikos Kakaounakis was threatened with arrest and torture for his coverage of resistance trials. There were niggling persecutions in which the charges were so transparently manufactured as to make a mockery of the judicial process. In the spring of 1971, there were three cases in as many months. |

|

|

Lambrakis and Karapanayotis were prosecuted for publishing stories which could 'mislead public opinion and do harm to Greece's foreign relations.' The charges arose out of articles concerning a sixteenth century Roman Catholic church in Crete which the government had demolished despite protests by archaeologists and architects. Vima's stories, it was alleged, threatened to damage relations with the Vatican and other Catholic nations, a charge so ludicrous that when the case came to court, even the prosecutor suggested that the two men should be acquitted. In a second case, a week later, the publisher and editor of Nea, Costas Nitsos and Vassilios Varikas, were charged with obscenity for having published a photo of a nude dancer at Paris' Crazy Horse Saloon. Again by the end of the hearing the prosecutor recommended the defendants' acquittal. The third charge was more substantial. Nea had published an article on western intellectuals by a Soviet professor but had changed the by-line. Eleftheros Kosrnos ran a series of editorials accusing them of |

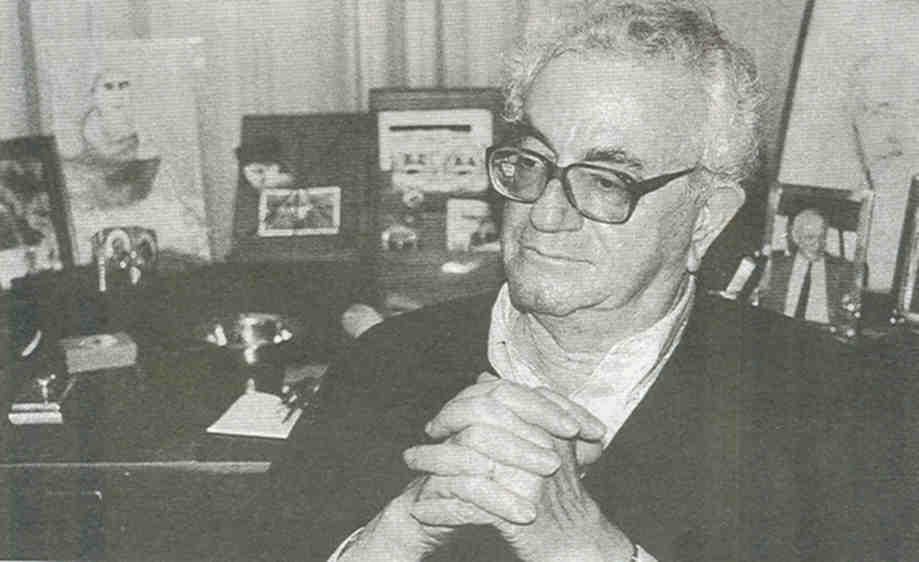

Leon Karapanayotis, publisher if To Vima in 1970 described a police interrogation thus: 'You would be brought in anad Theofylloyannakos would scream and shout at you. Then you'd be locked in a room for a couple of hours until you thought you were under arrest when, suddenly, they'd let you go. The next time you'd be put in a room and curious characters would be brought in to stare at you. Hadjizisis would say, "You don't know Mr. Mallios? Mr. Babalis? Let me introduce you," and then they'd all go away again.' Theofylloyannakos and Hadjizisis were both Military Police officers with public reputation as torturers: Mallios and Babalis were similarly notorious security police officers |

|

publishing 'contraband communist ideas.' Nitsos and Varikas were convicted of a breach of the press law and each sentenced to four months' imprisonment. Varikas' testimony before the court spoke eloquently of the strain. The day after the two men were convicted, Lambrakis and Karapanayotis both published signed articles on political subjects for the first time since the lifting of prior censorship. Karapanayotis insists that it was mere coincidence but it has been suggested that this was the quid pro quo for a subsequent successful appeal in which the verdict against the Nea editors was overturned. The cabinet reshuffle was meant to mark the beginning of a process of transformation from a revolutionary to a guided political regime. Pattakos and Makarezos were kicked upstairs from their vital posts at the Ministries of the Interior and of Economic Coordination to become largely titular Deputy Ministers, and senior civilians who had proven particularly loyal to the regime were elevated to their ministerial positions. Other former junta members were sent off to become governors of recently created regional administrations, being replaced in cabinet with new men, some of whom came from the Advisory Committee on Legislation, the so-called mini-parliament. This was a body of 56 members selected by the Prime Minister following a preliminary balloting procedure carried out by a college of 1,240 state-nominated electors. It met in the old parliament building and discussed draft laws presented to it by the government although its opinions were in no way binding and it had no power to generate legislation. It was designed primarily to give public exposure to 'new personalities' for the New Democracy. In a cabinet reshuffle in 1972, Papadopoulos included a number of minor former politicians, but none of these people were the sort who could appeal to the public to command widespread support. The end result of these moves was that, contrary to the intention of broadening the base of government, all significant powers were consolidated in Papadopoulos' hands, producing a one-man dictatorship of the Latin American style. He became Prime Minister, Defense Minister, Foreign Minister and Minister of Government Policy. On March 22, 1972, after a row with Zoitakis, he also became Regent. The regime was stagnant. Gradually, it began to crumble under the weight of its own inertia. The author is a journalist who has been covering Greek affairs for 40 years. The text is excerpted with permission from his book Pillar and Tinderbox, the Greek Press and the Dictatorship, published in 1983. |

|

|

|

|

|

(Posting date 11 May 2007) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|