|

||

|

The Coup at 40 Stopping the Press (Part 1 of 3) |

||

|

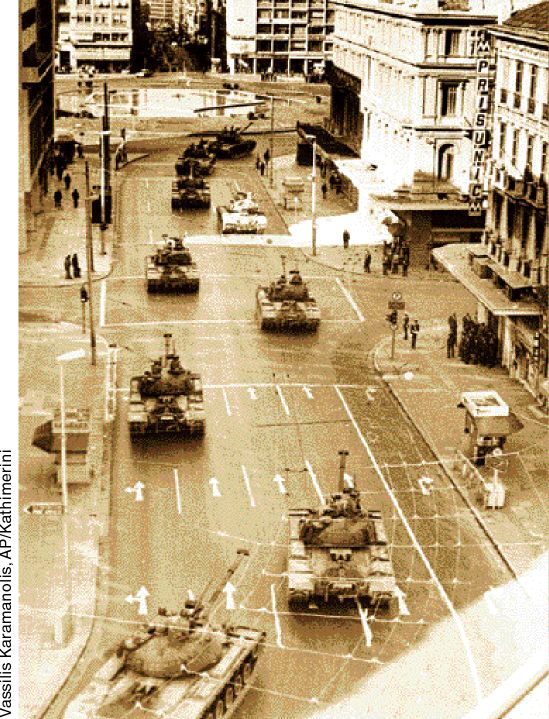

Forty years ago, a group of colonels suspended parliamentary democracy andpress freedom in Greece. Their dictatorship would last seven years and endwith the disastrous invasion of Cyprus. In the third instalment of a five-week-long series of eyewitness accounts now out of circulation,Robert McDonald describes how the dictators tried to strong-arm the press into supporting them On April 21, 1967, the colonels declared a state of emergency and activating a Nato counter-insurgency plan which caused the army to seize control of the country. They did it in the name of Constantine, though he later disowned their action. As their tanks trundled into central Athens shortly after two a.m. Prime Minister Kanellopoulos was roughly arrested; so too were the Papandreous, father and son. |

Greek army tanks roll through central Athens on 18 November 1973, a day dispersing a student uprising. The movement opposed the military dictatorship that ruled Greece from 1967. The military action against the students caused dozens of deaths and helped hasten the fall of the military junta in 1974. |

|

|

potentially hostile editors including Lambrakis, Kokkas and the two Center Union M.P. s who ran Athinaiki, Ioannis Papageorgiou and Emmanuel Baklatzis. The morning papers had already gone to bed when news of the troop movements started to trickle in. Helen Vlachou was awakened at home by staff and went immediately to the office to supervise the rewriting of a new lead. The material was all very tentative and Kathimerini set only one column reporting military movements and noting that soldiers had several times threatened to fire on inquiring reporters. "We did not expect to circulate, but we made the change out of habit, in spite of still having little to say."

Foreign editor Michael Biotakis was the late man at Avgi. He opened a hole in the back page and inserted a short item saying there had been military movements giving the impression of a coup. He stuck a headline above the page-one logo and ordered the print run started immediately. A handful of these copies actually got to kiosks, because the military didn't close the central distribution agency until six a.m. The issues were, however, confiscated before any could be sold. As the extent of the military movements began to become apparent, Christos Lambrakis left Vima together with editor-in-chief Leon Karapanayotis. They went to the home of a mutual friend where they spent the night trying to get information and debating what to do. According to Karapanayotis, "We discussed mainly what was going on rather than the paper. No one knew what was happening. On that first night we had no understanding of what to do." About dawn, it was agreed that Lambrakis should go underground until the situation was clarified while Karapanayotis would sound out the staff about whether to continue publishing. The decision, taken after much agonizing, was that the papers should remain open despite censorship in order to be able to fight another day. Lambrakis subsequently indicated that he concurred in this 'excruciating' choice. Lambrakis stayed a week at this apartment which belonged to a friend who had been a member of the resistance during the occupation and who was skilled at clandestine activities. He then was transferred to the home of dance impressario Dora Stratou where he was eventually arrested on June 1. Held for several weeks in solitary confinement at a gendarmerie headquarters in the Athens suburb of Goudi, he was later exiled to the island of Syros. At no time was he charged with anything except the vague assertion made by Public Order Minister Paul Totomis that he was a "danger to the security of the state". Lambrakis was finally liberated in an amnesty at Christmas 1967 but refused to go to his office until after the lifting of prior censorship nearly two years later. Panos Kokkas, publisher of Eleftheria, had been in court late on April 20 fighting a libel action brought against him by Kanellopoulos and Mrs. Vlachou over the publication of the aide memoire. Kokkas' sister, returning home about 1.30 a.m., spotted the tanks moving towards town and was able to alert him before telephone lines were cut. Kokkas had been expecting something like this and immediately went underground to avoid arrest. An hour later, a jeep with seven soldiers in it called at the Kokkas' home. When they could not find Panos, they took his seventy-six year old father as a hostage. At Eleftheria's printing works they found editor-in-chief, George Androulidakis, working on the stone and arrested him too. Kokkas remained inside Greece for nearly a month until arrangements were made for him to leave the country by means of a ship sailing from the west coast port of Patras. This he did in classic cloak and dagger fashion, kitted out in a disguise to get past military checkpoints. Kokkas' sister claims that during their first telephone call, even before he knew the political stripe of the junta, he asked her to announce to the staff that the paper would not publish so long as there was censorship. Eleftheria was closed down by the family and the staff were paid off at substantial cost. Kokkas remained abroad until 1973 when he returned following the lifting of martial law. The Athinaiki publishers both managed to escape arrest and to go into hiding. Papageorgiou in Athens, Baklatzis in Crete. The paper continued to be brought out by a team of journalists, although, according to Papageorgiou, this was done "without the permission of the publishers, who didn't want to publish under these conditions." After two weeks, it closed and charges were preferred against Papageorgiou and Baklatzis for non-payment of Easter bonuses and a fortnight's wages. Baklatzis was tricked into giving himself up by a false radio news report which said that he was hiding unnecessarily as there were no charges outstanding against him. He returned to Athens and was arrested as he stepped off the boat in Piraeus. Papageorgiou emerged after the prosecutor of the Athens Extraordinary Court Martial declared that unless he presented himself for questioning within twenty-four hours, he would be considered a fugitive. He appeared before a very fat colonel. "Why did you close the paper?" "I didn't close the paper." "I'll teach you. You will go inside." "Why will I go to prison?" "To teach you not to be insubordinate to the military authorities." "But I'm not being insubordinate. Once I got the summons I came straight away." "I'll teach you. You are going to prison for five years." The two publishers were remanded in custody for several months, a procedure unheard of on such charges. That it was only a pretext for incarceration on political grounds was amply demonstrated by the terms on which they were released. The newspaper was to shut down permanently but the government was not to be seen to have been the cause. The pair were to declare voluntary bankruptcy. Papageorgiou claimed that while the paper had debts, "commercial debts with the agencies, with paper merchants, the usual type of debts," nothing was owed to the bank and there was no need to wind up the business. He advised against accepting the terms and argued in favour of declaring force majeure, but it was Baklatzis who had ultimate financial authority for the paper and he, wanting out of prison, agreed to file the bankruptcy petition. They were released in September 1967. Baklatzis died of cancer three months later. Leonidas Kyrkos and Manolis Glezos, respectively publisher and director of Avgi, were held on the military's list of proscribed persons and were among the first to be arrested. Military police hustled Kyrkos from his house in his pyjamas while Glezos was snatched from sleep in his underwear. The editorial staff, putting the paper to bed at the Ethnos printing works, were not molested. After adding his insert, Biotakis and two colleagues repaired to a suburban apartment. En route, they were stopped by a policeman who asked for identification. They explained that they were journalists without producing their identity cards and were waved on their way with apologies. Only later, when they attempted to return to the paper and were turned back at a military roadblock, did they realize the full gravity of the situation. The three men went into hiding and were underground until September when they were arrested and interned. Dimokratiki Allagi shared a printing plant with Eleftheria and editor-in-chief Harilaos Manos, together with two senior staff, were actually in the works when the soldiers barged in to arrest Androulidakis. The trio slipped out of a side door and alerted director Lefteris Voutsas at home. He later joined them in an all-night coffee shop. Like everyone else, these men did not know on whose part the military was moving but they assumed it was the right and that they should act defensively. Their first thought was to get at the office safe. April 21 should have been payday and it was full of made up wage packets. The men wanted to ensure that these funds could be saved for resistance action. Taking the newspaper's car and driver, they reconnoitred the office area but, as the premises were above a police station and across the street from a major telecommunications centre, they found the district alive with troops and so had to detour to avoid detection. When the first morning radio bulletins confirmed their suspicions about the political complexion of the coup, they proceeded to a safe house where they remained for four days before going underground. One of them escaped to Paris but two others were quickly arrested. Voutsas managed to avoid detection for three months, long enough for him to have set the wheels in motion for an underground Avgi. It later became Rizospastis (Machitis) (Radical Fighter), a monthly paper which appeared for 65 issues as the voice of the Greek Communist Party of the Interior (K.K.E.-E.s), a Eurocommunist splinter from the orthodox party. The K.K.E. published its own underground papers beginning with Adouloti Athena (Unenslaved Athens) and later its own version of Rizospastis. It appeared for 67 issues until February 1974 when it was closed following a series of arrests of top level party leaders in the underground. There was a host of resistance publications produced during the dictatorship but it was only these communist papers which appeared regularly in printed form. They were produced at great risk and many people associated with them were arrested and tried for subversion. In the initial roundup of communists on April 21, some 20 regular working journalists were detained and interned, first at Yiaros and later at Leros prison camp. The property of Avgi and Dimokratiki Allagi was confiscated by the military and dispersed among state offices. Their printing plant and office facilities were rented and therefore could not be punitively seized in this way. |

||

|

The conservative publishers were not bothered by the military but the greatest shock for the junta came from among right wing ranks when Helen Vlachou decided to close her prestigious papers rather than to publish under censorship. The colonels had expected Kathimerini and Mesimvrini to be the flagships of their revolution. Mrs. Vlachou had effectively endorsed military intervention in print and, had the coup been by the king and his generals (the so-called 'big junta'), Kathimerini, at least, would likely have continued to appear even under censorship. As it was a pre-emptive strike by junior officers, and, because the colonels dictated as well as censored the news, Mrs. Vlachou refused to publish. This position was not immediately made apparent as she feared the regime might find some means to force her to appear. "We were 99 percent certain that we didn't want to publish but we didn't want that to come out too soon." Under the Nazi occupation, her father had openly declared his intention to close Kathimerini and the Germans had thrown him out and put in their own people. "This time we knew better. Unless we could publish a respectable paper, a newspaper that was free to inform and not obliged to misinform, we would not publish anything at all. But we were not going to advertize our decision." |

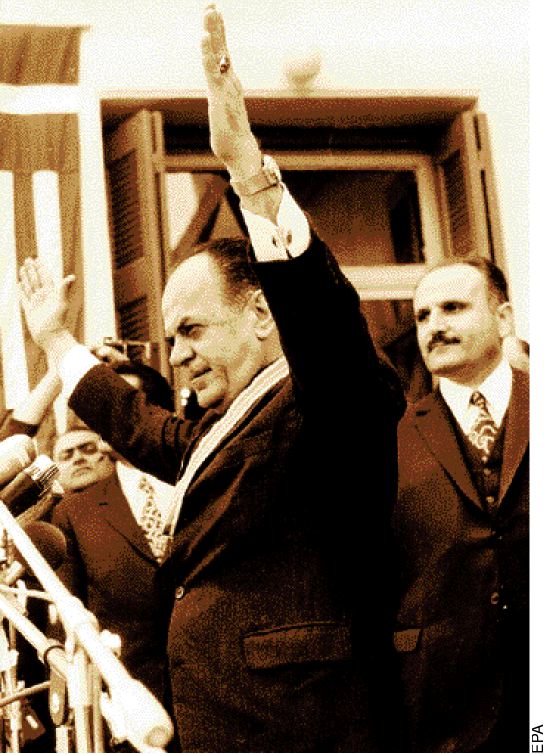

George Papadopoulos didn't appear in public for two months after the coup, but when he did he began to make speeches that couched Greece in terms of a patient undergoing surgery |

|

|

Giving her staff temporary leave, Mrs. Vlachou retired to her villa in the suburb of Pendeli where she was barracked by other publishers. "They were rather bitter with us. They said, 'Why do you let us suffer this indignity and you don't share it?' "The junta also sent emissaries to appeal for cooperation. She has cited Brigadier Pattakos as saying, "There is not going to be any censorship for you... We know you will write the right things. You will not be treated like the others. You will help us, guide us! We will create a new Greece together." But Mrs. Vlachou was adamant and on May 1 she issued redundancy notices, claiming force majeure. The action made her a symbol of resistance and she became a focus of attention for visiting foreign correspondents. She was placed under house arrest in October 1967 after giving an interview to La Stampa in which she referred to the colonels generally as mediocre men and to Brigadier Pattakos in particular as a clown. She managed to escape abroad to England in the confusion following the king's abortive counter-coup and settled there as a leading campaigner against the colonels. |

||

| Whether Farmakis' version of events is to be believed or whether he was squeezed out as a consequence of a dispute between Papadopoulos and Pattakos remains an open question. In any case, he was replaced by Colonel Constantine Karydas who, while not an actual member of the junta, was a close associate. Records show that Karydas officially assumed the title of Director General of Press and Information on May 29, although Farmakis recollects that he handed over to him informally on April 27 with "a chat to bring him up to date". On April 29, the informal censorship committee was transformed into an official Press Control Service headed by an officer of the Military Justice Department, Colonel Elias Papapoulos with a brief to "take instructions from and be responsible to us [Papadopoulos] for every oversight or omission in the preventive control of every sort of published printed matter." The Ministerial decision set out general instructions which gave the Service absolute control over all aspects of newspapers including copy, headlines, |

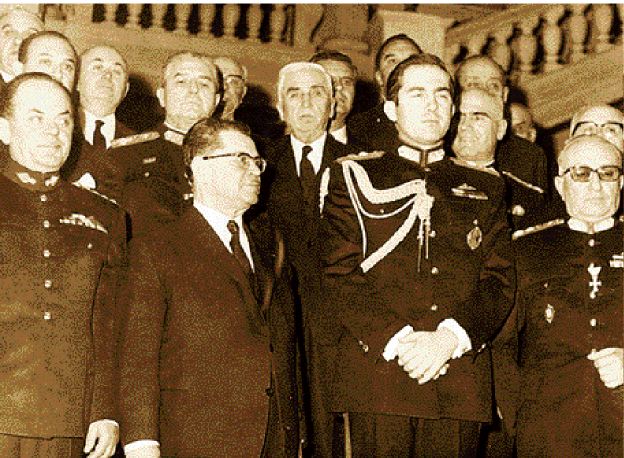

King Constantine gave a veneer of legitimacy to the dictators until his abortive counter-coup and flight from Greece in December 1967. He is seen here (C) swearing in the first government under the colonels. Colonel Papadopoulos (front L) stands behind the king's choice for prime minister, Konstantinos Kollias (bespectacled), a former attorney- general of the Supreme Court and a royalist |

|

| pictures, make-up and even the alleged opinions contained in editorial comment. The Service handouts comprised incessant, tedious accounts of formal official functions coupled with interminable texts of banal ministerial speeches. There was no news sense. The day the Arab-Israeli war broke out, the censors consigned the story to half a column on the back page, while the lead for the day was the 'triumphal' tour of Crete by Deputy Premier Spantidakis. Occasionally, the Service made absurd mistakes like insisting on typefaces for headlines too large for the space designated. The leeway of newspapers for personal expression was so circumscribed that they resorted to little tricks like putting front page stories below the fold where they wouldn't show while on display at kiosks. The censors retaliated by dictating layout as well. The most sinister feature was the way in which the regime dictated lies about former politicians in order to discredit them. For example, all papers were ordered to publish documents said to prove the links between Andreas Papandreou and A.S.P.I.D.A. which also implicated the elder Papandreou. They were later proved to be forgeries but there was no possibility of reply or redress for the injured parties. Moreover, newspapers were forced to appear to endorse the lies they propagated through dictated editorials. The tone is typified by this page one commentary imposed on Vimo which, prior to the coup, was a pro-Papandreou paper. For two years this country has been shaken by the affair of the communist organization A.S.P.I.D.A. and for two years Mr. Papandreou and those shouting with him have waged with tenacity the dirty battle of corrupting facts and strangling truth and slandering every institution, their only objective being to save from the people's verdict the persons who bear the greatest guilt for this inner undermining of Greece, namely himself and his son. Already, with a large crashing sound, with an earthquake, with country-wide denunciation, the unstable construction of the 'defense' of Papandreou has collapsed. In a text smuggled from jail, Lambrakis complained about the dictation of these 'imbecile commentaries' which he said 'violated' the Greek press. |

||

| Such blatant propaganda eventually proved counterproductive for the public stopped buying newspapers. Circulation dropped nearly 40 percent between April and July, from a daily average sale of 834,111 to 509,554. The closure of so many newspapers was partly responsible; their sales comprised a potential two-thirds of the lost copies. Equally, readers who lost their regular paper didn't bother to change to another. Not only was the news the same from one to the next, it was identical to that which could be heard on the radio. To try to get round the problem, the colonels sought to have newspapers publish on their own responsibility. In late May, soundings were taken among the pro-regime papers, Eleftheros Kosmos, Estia and Vradyni, but their reaction was that, as long as martial law remained in force, they preferred prior censorship because of the legal |

The emblem of the dictatorship was a phoenix rising from the ashes, with a soldier in silhouette within it |

|

|

protection it afforded. So, a tactic was adopted whereby on some stories, the Press Control Service, instead of issuing complete texts, issued detailed notes, requiring the newspapers to rewrite them. This got round the problem of uniformity of style while retaining control over substance. It gave newspapers a fractional margin for opposition. The situation is best illustrated by example. On June 21, 1967, Richard Nixon, passing through Athens on a fact-finding tour, held a brief airport press conference. The Press Control Service issued the following guidelines. |

||

|

|

||

(Posting date 8 May 2007)

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||